Sockeye Salmon

(Oncorhynchus nerka)

Printer Friendly

Did You Know?

The striking orange color of sockeye salmon flesh comes from eating plankton and krill while in the ocean.

General Description

Sockeye salmon are one of the smaller species of Pacific salmon, measuring 18 to 31inches in length and weighing 4-15 pounds. Sea-going sockeye salmon have iridescent silver flanks, a white belly, and a metallic green-blue top, giving them their "blueback" name. Some fine black speckling may occur on the back, but large spots are absent. Sockeye salmon are prized for their firm, bright-orange flesh.

As sockeye salmon return upriver to their spawning grounds, their bodies turn brilliant red and their heads take on a greenish color, hence their other common name, “red” salmon. Breeding-age males develop a humped back and hooked jaws filled with tiny, visible teeth. Juveniles, while in fresh water, have dark, oval parr marks on their sides. These parr marks are short-less than the diameter of the eye-and rarely extend below the lateral line.

Life History

Like all species of Pacific salmon, sockeye salmon are anadromous, living in the ocean but entering fresh water to spawn. Sockeye salmon spend one to four years in fresh water and one to three years in the ocean.

In Alaska, most sockeye salmon return to spawn in June and July in freshwater drainages that contain one or more lakes. Spawning itself usually occurs in rivers, streams, and upwelling areas along lake beaches. During this time 2,000 – 5,000 eggs are deposited in one or more “redds”, which the female digs with her tail over several days time. Males and females both die within a few weeks after spawning.

Eggs hatch during the winter, and the young “alevins” remain in the gravel, living off their yolk sacs. In the spring. they emerge from the gravel as “fry” and move to rearing areas. In systems with lakes, juveniles usually spend one to three years in fresh water, feeding on zooplankton and small crustaceans, before migrating to the ocean in the spring as “smolts”. However, in systems without lakes, many juveniles migrate to the ocean soon after emerging from the gravel.

Smolts weigh only a few ounces upon entering salt water, but they grow quickly during their 1-3 years in the ocean, feeding on plankton, insects, small crustaceans, and occasionally squid and small fish. Alaska sockeye salmon travel thousands of miles during this time, drifting in the counter-clockwise current of the Alaska Gyre in the Gulf of Alaska. Eventually they return to spawn in the same freshwater system where they were hatched.

Range and Habitat

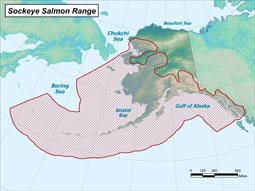

Fresh water lakes, streams and estuaries provide important habitat for spawning and rearing sockeye salmon. On the west coast of North America, sockeye salmon range from the Klamath River in Oregon to Point Hope in northwestern Alaska.

The largest sockeye salmon populations are in the Kvichak, Naknek, Ugashik, Egegik, and Nushagak Rivers that flow into Alaska’s Bristol Bay, plus the Fraser River system in Canada. In good years, these runs can number in the tens of millions of fish.

Status, Trends, and Threats

Pacific salmon species on the west coast of the lower 48 United States have experienced dramatic declines in abundance during the past several decades as a result of several factors, including water diversions for agriculture and flood control; loss of habitat due to hydropower, resource extraction and development; and direct mortality from entrainment by hydropower projects. As a result, two lower-48 populations of sockeye salmon have been listed under the Endangered Species Act.

For the time being, salmon habitat in Alaska remains mostly pristine. There are hundreds of stocks of sockeye salmon throughout the state of Alaska and their population trends are diverse: Some stocks are in decline while others are at equilibrium or increasing. Potential future threats include habitat loss, habitat degradation, climate change, and over fishing.

Fast Facts

-

Size

Length = 24 inches (Record: 31 inches); Weight = 6 lbs (Record: 16 lbs). -

Lifespan

3 to 7 years -

Distribution/Range

North America "– Klamath River, OR to the Chukchi Sea. Asia – Hokkaido, Japan to Anadyr River, Siberia -

Diet

Zooplankton,small crustaceans, small fish -

Predators

Marine mammals, bears -

Remarks

The most economically important species of salmon in Alaska -

Other Names

Red and blueback salmon, kokanee (landlocked form in lower 48 states and Canada) -

Stock Status

3rd most abundant species of Pacific salmon. Populations currently healthy in Alaska. Human induced habitat loss and direct mortality has depressed populations in the lower 48 states.

Did You Know?

- The striking orange color of sockeye salmon flesh comes from eating plankton and krill while in the ocean.

- Landlocked sockeye salmon rarely grow to more than 14 inched in length and are called “kokanee”.

- Sockeye salmon are the most economically important species of salmon in Alaska.

- Salmon use their sense of smell (“olfaction”) to recognize their home stream.

- Sockeye salmon filter zooplankton and other small animals from the water with their “gill rakers”.

Uses

Sockeye salmon are the most economically important salmon in Alaska. More pink salmon are caught, but sockeye salmon are a higher quality fish and sell for a much higher price.

Commercial Fishery

The largest harvest of sockeye salmon in the world occurs in the Bristol Bay area of southwestern Alaska where 10 million to more than 30 million sockeye salmon may be caught each year during a short, intensive fishery lasting only a few weeks. Relatively large harvests of one million to six million sockeye salmon are also taken in Cook Inlet, Prince William Sound, and Chignik Lagoon. All commercial Pacific salmon fisheries in Alaska are under a limited entry system which restricts the number of vessels allowed to participate. Most sockeye salmon are harvested with gillnets either drifted from a vessel or set with one end on the shore, some are captured with purse seines, and a relatively small number are caught with troll gear in the southeastern portion of the state.

Subsistence Fishery

Subsistence users harvest sockeye salmon in many areas of the state. The greatest subsistence harvest of sockeye salmon probably occurs in the Bristol Bay area where participants use set gillnets. In other areas of the state, sockeye salmon may be taken for subsistence use in fishwheels. Most of the subsistence harvest consists of prespawning sockeye salmon, but a relatively small number of postspawning sockeye salmon are also taken.

Sport Fishery

There is also a growing sport fishery for sockeye salmon throughout the state. Probably the best known sport fisheries with the greatest participation occur during the return of sockeye salmon to the Kenai River and one of its tributaries the Russian River on the Kenai Peninsula. Other popular areas include the Kasilof River on the Kenai Peninsula as well as the various river systems within Bristol Bay and Kodiak Island. Sockeye are highly prized by sport anglers for their tenacious fighting ability as well as food quality.

Personal Use Fishery

Personal use fisheries have also been established to make use of any sockeye salmon surplus to spawning needs, subsistence uses, and commercial and sport harvests. Personal use fisheries have occurred in Bristol Bay, where participants use set gillnets, as well as in Cook Inlet and Prince William Sound, where participants also use dip nets.

Viewing

In the summer, there are many opportunities to view spawning sockeye salmon in the wild, providing a boon to Alaska’s growing tourism industry.

Processing

Sockeye salmon are the preferred species for canning due to the rich orange-red color of their flesh. Today, however, more than half of the sockeye salmon catch is sold frozen rather than canned. Canned sockeye salmon is marketed primarily in the United Kingdom and the United States while most frozen sockeye salmon is purchased by Japan. Sockeye salmon roe is also valuable. It is salted and marketed in Japan.

Recipes

- Alaska seafood recipes

- Salmon in Lime Ginger Sauce

- Fish Soup

- Salmon with Gnocchi and Roasted Red Pepper

- Dishwasher Salmon

- Honeymoon Salmon

- Simple Smoked Salmon

- Smoked Salmon Mousse

- Dutch Oven Salmon Casserole

- Salmon and Corn Chowder

- Fish Facts and Consumption

Management

The Alaska State Constitution establishes, as state policy, the development and use of replenishable resources, in accordance with the principle of sustained yield, for the maximum benefit of the people of the state. In order to implement this policy for the fisheries resources of the state, the Alaska Legislature created the Alaska Board of Fisheries (BOF) and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G).

The BOF was given the responsibility to establish regulations guiding the conservation and development of the state’s fisheries resources, including the distribution of benefits among subsistence, commercial, recreational, and personal uses. The ADF&G was given the responsibility to implement the BOF’s regulations and management plans through the scientific management of the state’s fisheries resources. Scientific and technical advice is also provided by the ADF&G to the BOF during its rule-making process. The separation of rule-making and inseason management responsibilities between these two entities is generally regarded as contributing to the success of Alaska’s fisheries management system.

The ADF&G’s fishery management activities fall into two categories: inseason management and applied science. For inseason management, the department deploys a cadre of fishery managers near the fisheries. These individuals have broad authority to open and close fisheries based on their professional judgment, the most current biological data from field projects, and fishery performance.

Research

Research biologists and other specialists conduct applied research in close cooperation with the fishery managers. The purpose of the division’s research shop is to ensure that the management of Alaska’s fisheries resources is conducted in accordance with the sustained yield principle and that managers have the technical support they need to ensure that fisheries are managed according to sound scientific principles and utilizing the best available biological data.

A variety of research is conducted each year throughout the state that explores topics such has stock and harvest assessment, population dynamics, genetic stock identification, and stock assessment technologies. Such projects are often conducted in collaboration with university, federal and international institutions. The results of these works are peer-reviewed and presented as written articles as well as presented at scientific conferences and meetings throughout the world.

Get Involved

Regulatory Process

Volunteer in Schools Programs

In Your Community

More Resources

Sockeye salmon

Commercial, Sport, Subsistence, and Personal Use Fishing

- How to Fish for Klutina River Red Salmon (Video)

- Commercial Fishing

- Sport Fishing

- Subsistence Fishing

- Personal Use Fishing

- Angler Education

- Salmon Enhancement and Hatcheries

- Salmon Forecasting in Alaska: Who Needs to Know?

- Fish Counts

Viewing

Conservation and Education

- Sockeye Salmon — Wildlife Notebook Series (PDF 51 kB)

- Fish Passage Improvement Program

- Dead Salmon Bring Life to Rivers