Sperm Whale

(Physeter macrocephalus)

Printer Friendly

Did You Know?

Sperm whales are the largest of the toothed whales.

General Description

The famed fictional sperm whale Moby Dick was characterized as "the great white whale," but sperm whales are mostly dark, charcoal grey, though some have white patches on the belly. Their skin is often wrinkly. They exhibit extreme sexual dimorphism: Adult males (bulls) average 52 feet long (16 meters, but some exceed 60 feet or 18 meters) and 45 to 50 tons (46,000 -50,000 kilos); adult females are about 36 to 40 feet (11 m - 13m) and average about 15 tons (15,000 kilos).

Sperm whales have a distinctive, single blowhole on the left side of the head near the end of their blunt snout, which may extend up to five feet beyond the end of their narrow, underslung jaw. Their blow is low, bushy, and angled forward and left as a result. Their head, the largest in the animal kingdom, is about a third the length of their body. They tend to raise their broad tail flukes high in the air when diving (they usually drop vertically when diving). These characteristics make these whales are relatively easy to identify when seen. Adult males rarely breach, but juvenile whales commonly breach and lobtail.

Life History

Female sperm whales reach sexual maturity around 9 years of age when they are roughly 29 feet long (nine meters). At this point, growth slows and females are physically mature around 30 years of age and 35 feet long, at which time they stop growing.

A female may give birth to a calf once every five to seven years. After a 14 to 16-month gestation period, a single calf about 13 feet (four meters) long is born. Although calves will eat solid food before one year of age, they continue to nurse for several years.

For about the first 10 years of life, males are only slightly larger than females, but males continue to grow until they are well into their 30s. Males reach physical maturity and full size around 50 years. Unlike females, puberty in males is prolonged, and may last between ages 10 to 20 years old. Even though males are sexually mature at this time, they often do not actively participate in breeding until their late twenties.

Sperm whales are social animals; females and juvenile males live together in groups. Most females will form lasting bonds with other females of their family, and on average 12 females and their young will form a social unit. While females generally stay with the same unit all their lives in and around tropical waters, young males will leave when they are between 4 and 21 years old and migrate to higher latitude feeding grounds; here they can be found in "bachelor schools," comprised of other males that are about the same age and size. As males get older and larger bachelor schools tend to become smaller; the largest males are often found alone but within acoustic hearing distance of other males. Large, sexually mature males in their late 20s and older will occasionally return to the tropical breeding areas to mate They live about 60 years.

Sperm whales are noteworthy for their acoustic activity which they use to navigate, hunt, and communicate. They emit sounds described as clicks, creaks, clangs, and codas.

Sperm whales dive to lightless depths so they rely on sound to navigate, communicate, and forage. The most common echolocation signals produced by sperm whales are "usual clicks," which occur about once every second and are used for navigation and foraging. A sperm whale can detect the size, and density of its prey or the bottom of the ocean, based on the return signal bouncing off the object and this is how they "see" underwater. In addition to "usual clicks" sperm whales produce a foraging buzz known as a "creak," that has a very high repetition rate, when they hone in on their prey to attempt to capture it. In high latitudes, males are known to also produce a loud metallic sound called a "clang", that is often described as a twangy gunshot sound. Clangs are generally produced in a series, with a slow repetition rate, every 5 to 8 seconds. When sperm whales socialize in their large family groups, the females and claves emit complex patterns of clicks called codas.

Codas have not been heard by researchers studying sperm whales in the Gulf of Alaska, but most of the whales known in the Gulf are males.

Diet

Sperm whales hunt for food during deep dives that routinely reach depths of 2,000 feet (610 meters) and can last for 45 minutes, intervals at the surface between dives may be five to 15 minutes. They are capable of diving to depths of over 10,000 feet (3,050 meters) for up to two hours. After long, deep dives, individuals come to the surface to breathe and recover for up to an hour. Research tracking diving whales in equatorial waters suggests that family groups in these regions also engage in cooperative hunting efforts such as herding prey.

Whale researcher Lauren Wild analyzed dive data from satellite tags on male sperm whales off the eastern Gulf of Alaska and found that dives there average 400 m and last an average of 32 minutes, with a nine-minute surface interval.

Because sperm whales spend most of their time in deep waters, their diet consists of many larger species that also occupy deep ocean waters. In warmer water regions, and in the offshore deep ocean basin regions, they primarily eat squid. In higher latitudes, where mostly males are feeding, their diet becomes more diverse, including sharks, skates, and fish in addition to squid. Sperm whales can consume about 3 to 3.5 percent of their body weight per day.

The most common predator of sperm whales is the killer whale. Killer whales target groups of females with young, usually trying to extract and kill a calf. Adults will protect their calves or an injured adult by encircling them.

Range and Habitat

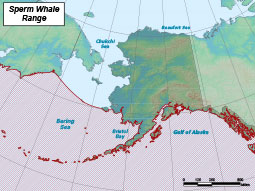

Sperm whales inhabit most of the world's oceans. Their distribution is dependent on their food sources and suitable conditions for breeding and varies with the sex and age composition of the group. Sperm whale migrations are not as predictable or well understood as migrations of most baleen whales. In some mid-latitudes, sperm whales seem to generally migrate north and south depending on the seasons, moving toward the poles in the summer. However, in other tropical and temperate areas, there appears to be no obvious seasonal migration. A year-round presence has been documented in Alaskan waters from acoustic mooring buoys that detect echolocation clicks, though with a higher volume in summer than winter. Tagging data has also shown sperm whales leaving Alaska waters in summer months as well as fall and winter months.

In Alaska waters, male sperm whales were documented over the continental shelf edge (the slope) miles offshore back in whaling days. The whalers that took sperm whales off northern BC and eastern Gulf of Alaska specifically documented male bachelor groups on the shelf edge, where there is an abundance of deep sea fish and squid for them to eat. They tend to not come in shallower than 150 or 200 fathoms of water and are seen rarely in nearshore waters or the waters of Southeast Alaska's Inside Passage.

However, in the past 30 years there have been changes regarding sperm whales in the Gulf of Alaska and Southeast Alaska's Inside Passage. Sightings of sperm whales have become far more common, particularly by longliners fishing the Gulf of Alaska, where sperm whales have learned to take fish from longlines during fishing operations.

In the 1990s the sablefish fishery went to an Individual Fishing Quota (IFQ) system. The fishing season lengthened and there were boats constantly on the fishing grounds. This gave the whales time to figure out that these boats provided an easy meal, and how to take the fish. Prior to that, the fishery was so short (two weeks to a month) that they didn't have time to learn depredation behavior.

This has become a common practice and efforts are underway to address the problem (see the link to Southeast Alaska Sperm Whale Avoidance Project (SEASWAP) under more resources). Whales will nip fish neatly off the hooks leaving the head, or "floss," running the groundline through its mouth, stripping the fish and straightening the fishhooks. They also use the tension on the line to pop the fish off the hooks with their teeth without leaving any evidence of a fish, nor a straightened hook.

Another change is an apparent increase in presence in the Inside waters, specifically in Chatham where a few individuals probably followed a longliner in and figured out that there are sablefish in there, as well as squid. In the fall of 2018 and spring of 2019, three sperm whales were seen repeatedly in the Inside waters of Chatham Strait and Lynn Canal, and in March 2019 a dead sperm whale washed up north of Berners Bay between Juneau and Haines.

Status, Trends, and Threats

Sperm whales were a prime target of the commercial whaling industry and close to 1,000,000 sperm whales were killed worldwide by whalers between 1800 and 1987. There is evidence that some populations of sperm whales have been growing since sperm whaling halted. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA) estimates that, since the moratorium went into effect in 1986, their population has grown at about four percent a year.

As with the better-known humpback whales, distinctive markings and coloration on the tail flukes enable biologists to identify individual whales. They can also be identified by distinctive scarring on their heads and bodies, as well as unique shapes of their dorsal fin and the "knuckles" protruding on their backs between the dorsal fin and tail flukes. According to Alaska whale researchers with the SEASWAP program, The Gulf of Alaska Sperm Whale ID Catalog had 122 unique individuals at the start of the 2019 field season. A discovery curve shows the rate of new whales being "discovered" or photographed for the first time, is decreasing. This indicates that the SEASWAP team is close to having photographs of most individuals in the Eastern Gulf of Alaska near the study site of Sitka. However, the population of sperm whales that frequents Alaskan waters is an open population, meaning different whales come and go, making the estimation of abundance difficult.

Sperm whale actual population size is unknown — guesses range between 200,000 and 1,500,000 animals worldwide. The population in Alaskan waters is unknown. The sperm whale is listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act and depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) regards the sperm whale as being "Vulnerable".

Fast Facts

-

Size

Average length for males: 52 feet.

Average length for females: 36-40 feet. -

Diet

Squid, sharks, skates, and fish. In Alaska, more specifically, squid, elasmobranch fishes (mostly sharks and skates), and teleost fishes (sablefish, rockfish, lanternfish, and ragfish). -

Reproduction

One calf every four to seven years.

Did You Know?

- The sperm whale's huge head contains a waxy substance in a large cavity called the spermaceti organ. It is believed to aid in decreasing and increasing buoyancy during dives and may also be used to focus sonar clicks used to navigate and hunt underwater.

- The sperm whale has the largest brain of any animal on Earth, more than five times heavier than the human brain.

- Sperm whales have one of the widest global distributions of any marine mammal species. They are found in all deep oceans, from the equator to the edge of the pack ice in the Arctic and Antarctic.

- Hunting sperm whales could be dangerous to the crew of whaling ships, as sperm whales will defend themselves against attack, unlike most baleen whales. Sperm whales use their huge head effectively as a battering ram. A famous sperm whale counter-attack occurred on Nov. 20, 1820, when a whale rammed and sank the Nantucket whaleship Essex. Only 8 out of 21 sailors survived to be rescued by other ships. This is believed to have inspired Herman Melville's book Moby-Dick.

- Sperm whales are named after the waxy substance, spermaceti, found in their heads. Spermaceti was used in oil lamps, lubricants, and candles. from 1800 to 1987. Whaling greatly reduced the sperm whale population. Whaling is no longer a major threat and its population is still recovering.

- Sperm whales are the largest of the toothed whales.

Management

Sperm whales are federally managed by NOAA Fisheries.

More Resources

General Information

- Sperm Whale — Wildlife Notebook Series (PDF 70 kB)

- Whale Alert is a NOAA app that anyone can use to report whale sightings. You don't need to be in an area with cell service so long as your device is GPS enabled. The data you submit will be transmitted once you are in cell tower range. Real-time data from the Whale Alert app informs professional mariners when a whale is in the vicinity of their route so they can be extra vigilant and slow down. This helps to prevent vessel strikes.

- To report sperm whale sightings in Alaska: The number is (907) 586-7235. Photos are very helpful, especially for sperm whales or other rare species. It is very important to document sightings of these less seen species so that we can more accurately promote their conservation.

- To report injured, entangled or dead marine mammals, call the NOAA Fisheries statewide 24-hour stranding hotline: (877) 925-7773.

- Southeast Alaska Sperm Whale Avoidance Project (SEASWAP)

- Article from Molecular Ecology Resources: Sperm whale population structure in the eastern and central North Pacific

- More on the Lynn Canal dead sperm whale found in March 2019

- NOAA species page