Coho Salmon

(Oncorhynchus kisutch)

Printer Friendly

Did You Know?

Spawning coho males develop a prominent hooked snout called a kype.

General Description

Adults usually weigh 8 to 12 pounds and are 24 to 30 inches long, but individuals weighing 31 pounds have been landed. Adults in salt water or newly returning to fresh water are bright silver with small black spots on the back and on the upper lobe of the tail fin. They can be distinguished from Chinook salmon by the lack of black spots on the lower lobe of the tail and by their white gums; Chinook have small black spots on both tail fin lobes and they have black gums. Spawning adults of both sexes have dark backs and heads with maroon to reddish sides.

Life History

Growth and Reproduction

Coho salmon enter spawning streams from July to November, usually during periods of high runoff. The female digs a nest, called a redd, and deposits 2,400 to 4,500 eggs. As the eggs are deposited, they are fertilized with sperm, known as milt, from the male. The eggs develop during the winter, hatch in early spring, and the embryos remain in the gravel utilizing their egg yolk until they emerge in May or June. During the fall, juvenile coho may travel miles before locating off-channel habitat where they pass the winter free of floods. Some fish leave fresh water in the spring and rear in brackish estuarine ponds and then migrate back into fresh water in the fall. They spend one to three winters in streams and may spend up to five winters in lakes before migrating to the sea as smolt. Time spent at sea varies. Some males (called jacks) mature and return after only 6 months at sea at a length of about 12 inches, while most fish stay 18 months before returning as full size adults.

Feeding Ecology

In freshwater, coho fry feed voraciously on a wide range of aquatic insects and plankton. They also consume eggs deposited by adult spawning salmon. Their diet at sea consists mainly of fish and squid.

Migration

Little is known about the ocean migrations of coho salmon. High seas tagging shows that maturing Southeast Alaska coho move northward throughout the spring and appear to concentrate in the central Gulf of Alaska in June. They later disperse towards shore and migrate along the shoreline until they reach their stream of origin.

Range and Habitat

The emergent fry occupy shallow stream margins, and, as they grow, establish territories which they defend from other salmonids. Coho fry live in ponds, lakes, and pools within streams and rivers, usually among submerged, woody debris- in quiet areas free of current.

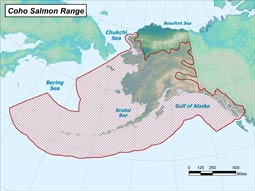

Coho are found in coastal waters of Alaska from Southeast to Point Hope on the Chukchi Sea and in the Yukon River to the Alaska-Yukon border. Coho are extremely adaptable and occur in nearly all accessible bodies of fresh water, from large trans-boundary watersheds to small tributaries.

Status, Trends, and Threats

Status

The status of coho populations in the California and the Pacific Northwest varies; some are healthy and robust while one is listed as endangered and three are considered threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Coho salmon populations in Alaska are healthy.

Trends

Over the longer term, the natural production of this species, particularly in the southern portions of its range, will continue to be challenged by freshwater environmental change brought about by increasing human development and climate change. Populations at lower latitudes will likely continue to experience greater variability in both smolt production and marine survival compared with Alaska's populations. Recent declines in hatchery production combined with environmental and management changes make it unlikely that the Pacific-wide commercial catch will rebound to levels in the mid-1960s to mid-1990s that routinely exceeded 10 million fish annually. Alaska's coho population is expected to remain healthy.

Threats

Coho salmon on the west coast of the United States have experienced dramatic declines in abundance during the past several decades as a result of human-induced and natural factors. Water storage, withdrawal, conveyance, and diversions for agriculture, flood control, domestic, and hydropower purposes have greatly reduced or eliminated historically accessible habitat. Physical features of dams, such as turbines and sluiceways, have resulted in increased mortality of both adults and juvenile salmonids.

Natural resource use and extraction leading to habitat modification can have significant direct and indirect impacts to salmon populations. Land use activities associated with logging, road construction, urban development, mining, agriculture, and recreation have significantly altered fish habitat quantity and quality. Studies indicate that in most western states, about 80 to 90 percent of the historic riparian habitat has been eliminated. Further, it has been estimated that during the last 200 years, the lower 48 United States have lost approximately 53 percent of all wetlands. Washington and Oregon's wetlands have been estimated to have been diminished by one third, while it is estimated that California has experienced a 91 percent loss of its wetland habitat.

Salmon have been, and continue to be, an important target species for recreational fisheries throughout their range. During periods of decreased habitat availability, the impacts of recreational fishing on native anadromous stocks may be heightened. Commercial fishing on unlisted, healthier stocks has caused adverse impacts to weaker stocks of salmon, and illegal high seas driftnet fishing in past years may have also been partially responsible for declines in salmon abundance. Introduction of non-native species and modification of habitat have resulted in increased predator populations and salmonid predation in numerous river and estuarine systems.

Fast Facts

-

Size

24-30 inches long, 8-12 pounds -

Range/Distribution

The traditional range of the coho salmon runs from both sides of the North Pacific Ocean, from Japan and eastern Russian, around the Bering Sea to mainland Alaska, and south all the way to Monterey Bay, California. Coho salmon have also been introduced in all the Great Lakes, as well as many other landlocked reservoirs throughout the United States. -

Diet

Aquatic insects, fish, squid -

Predators

Whales, sharks, marine mammals, birds, mammals, humans -

Reproduction

Deposit 2,400-4,500 eggs in freshwater from September-February -

Other Names

silver salmon

Did You Know?

- Coho spawn primarily occurs at night.

- Spawning coho males develop a prominent hooked snout called a kype.

- The female coho will deposit between 2,400 to 4,500 eggs.

- Precocious male coho known as “jacks” return as two-year old spawners.

- Coho can leap vertically more than 6 feet.

Uses

Commercial Fishery

The commercial catch of coho salmon has increased significantly from low catches in the 1960s, reaching 9.5 million fish in 1994. About half the commercially harvested coho were taken in Southeast Alaska, primarily by the troll fishery.

Subsistence Fishery

Coho salmon are utilized across the state of Alaska for subsistence needs.

Sport Fishery

The coho salmon is a premier sport fish and is taken in fresh and salt water from July to September. In 2005, anglers throughout Alaska caught 1.4 million coho salmon. In salt water they are taken primarily by trolling or mooching (drifting) with herring or with flies or lures along shore. In fresh water they hit salmon eggs, flies, spoons, or spinners. Coho are spectacular fighters and the most acrobatic of the Pacific salmon. On light tackle, coho provide a thrilling and memorable fishing experience.

Viewing

Recipes

- Alaska Seafood Recipes

- Salmon in Lime Ginger Sauce

- Fish Soup

- Salmon with Gnocchi and Roasted Red Pepper

- Dishwasher Salmon

- Honeymoon Salmon

- Simple Smoked Salmon

- Smoked Salmon Mousse

- Dutch Oven Salmon Casserole

- Salmon and Corn Soup

Management

The Alaska State Constitution establishes, as state policy, the development and use of replenishable resources, in accordance with the principle of sustained yield, for the maximum benefit of the people of the state. In order to implement this policy for the fisheries resources of the state, the Alaska Legislature created the Alaska Board of Fisheries (BOF) and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G).

The BOF was given the responsibility to establish regulations guiding the conservation and development of the state’s fisheries resources, including the distribution of benefits among subsistence, commercial, recreational, and personal uses. The ADF&G was given the responsibility to implement the BOF’s regulations and management plans through the scientific management of the state’s fisheries resources. Scientific and technical advice is also provided by the ADF&G to the BOF during its rule-making process. The separation of rule-making and inseason management responsibilities between these two entities is generally regarded as contributing to the success of Alaska’s fisheries management system.

The ADF&G’s fishery management activities fall into two categories: inseason management and applied science. For inseason management, the department deploys a cadre of fishery managers near the fisheries. These individuals have broad authority to open and close fisheries based on their professional judgment, the most current biological data from field projects, and fishery performance.

Research

Deep Creek Coho Salmon Assessment

"NAPA North to Alaska" feature - smolt study on the Unalakleet River LRV"

Unalakleet smolt research. A general overview about the smolt study on the Unalakleet River in 2011. We briefly talk about the use of the screw trap, how the smolt are analyzed, and why the study is important. About 6 minutes. Produced by Dan Foster - ZONK! Productions Inc. and segment used with permission.

Get Involved

- Alaska Board of Fisheries

- Fish and Game Advisory Committees

- ADF&G Internships

- Campbell Creek Science Center

- Eagle River Nature Center

More Resources

Coho Salmon

Fishing

- Commercial Fishing

- Sport Fishing

- Subsistence Fishing

- Personal Use Fishing

- Angler Education

- Salmon Enhancement and Hatcheries

- Salmon Forecasting in Alaska: Who Needs to Know?

- Fish Counts