Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

October 2021

Close to the Earth: Alaska’s Lanky Mustelids

I think my first encounter with a weasel, in Alaska, was in Hatcher Pass one summer. Of course, I knew of weasels from having grown up in the UK. I remembered reading in Roald Dahl’s Boy something about how female weasels will ferociously and fearlessly defend their young. They got a bit of a bad rap in the Redwall book series, where they were generally featured as villains. They seem to have a bit of a bad reputation generally, really; unsavoury characters in books and media are labelled as weaselly if they’re sneaky or devious. I’d always thought that was an unfair assessment.

As for the internet collective, well— they just call them catsnakes.

So, back to this weasel in Hatcher Pass; it gave me a solid once-over, decided I was bad news, and scurried across the trail into the undergrowth. It hardly was deserving of its unkind reputation; let’s be frank, it was cute, and amusing to observe. I looked it up later, because I had a vague sense that weasels and ermine might have been the same thing. Turns out that I saw either a Least Weasel (Mustela rixosa) or a Short-Tailed Weasel (Mustela erminea), the latter of which is also known as ermine and, in my former part of the world, stoat.

Did you know a new species of ermine, the Haida Ermine, was discovered in Alaska in March of this year? I certainly didn’t. More on that a bit later.

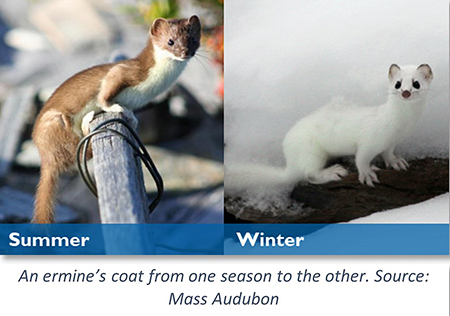

The basics

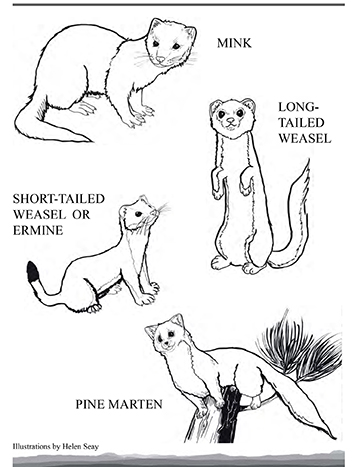

Let’s start with the basics. Weasels are members of the Mustelidae family; they’re the smallest of the group, which includes mink, marten, fisher, river otter, sea otter, and wolverine. Least weasels and ermine can be found across North America, as well as most of Alaska. Generally, by description, they have a small, pointed head with rounded ears, long whiskers, a long body, short legs, and a tail that varies depending on subspecies. Their colouration is generally variable shades of reddish-brown, and creamy-coloured from the throat to the underbelly. Their tails are tipped black, always; and in the wintertime, they turn white, save for the tail. Their soft fur provides warmth and insulation in the long winter months.

Now, their marked differences: short-tailed weasels – ermine, again – are about 15 inches (38 cm) in length, and weigh in at a colossal 7 ounces (198g, so shy of the weight of two cups of flour). The least weasel comes in at a whopping 3 ounces (85g, about as much butter as is acceptable in mashed potatoes), and is as long as 10 inches (25 cm). The short-tailed weasel’s tail is maybe 25% to 33% of their entire body length, while the least weasel’s comes in about 15%. Males are approximately 25% larger than females.

They’re ferocious little hunters. If their heads can fit, then so can they, and so they’ll pursue prey into burrows and tunnels. Agile and nocturnal hunters, ermine can take on prey over twice their size, such as rabbits, otherwise seeking out rodents, fish, frogs, rats, and even porcupine. Least weasels prefer smaller fare, like voles, but are nonetheless just as ferocious. This is especially important for the frigid winter season as they do not hibernate, and they power through on calories.

Weasels have been known to take on unwise humans that stand between them and their food; a hungry weasel is a fearless weasel.

Naturally, they have predators of their own to worry about, although not terribly much—the horned owl and marten are their main concerns, and to a lesser extent, hawks, foxes, coyotes, and lynx. Given that they’re such wily quarry, they give any hunters a run for their dinner.

Of course, humans also pose a threat with traps, loss of habitat, and a reduction in resources. Climate change disruption also has caused issues to arise with parasites, pathogens, and invasive species.

So how do they get that snowy coat?

Much like willow ptarmigan, arctic fox, and arctic hares, as I’ve already mentioned, ermine and least weasels trade their tawny coats for ones that echo our pristine, frosty winters. Once, on an aerial survey where I was assisting with counting moose, we flew over a stretch of wintry landscape. And there, smack-bang in the centre of a vast basin, there was a fire-orange fox. I can’t really speculate on what the fox’s plan was for blending into the landscape, but I was definitely questioning the fox’s survivability if it was standing out so brazenly.

I watched Russian Dwarf hamsters for a friend at school, once. They also swapped their grey-brown coats to a white one with a tidy grey stripe along their backs. They were kept indoors, so sixth-grade-me was given cause to wonder, how did they know?

So, how do other species (more sensibly coloured than the fox) know when to undergo the transformation? What triggers the change?

It comes down to a hormonal release due to the change in daylight hours, also known as the photoperiod. As we lose light as the Earth tilts away from the sun, a chemical reaction is triggered, altering the levels of melanin pigments. As they shed fur, the new growth takes on the lighter shades. This process is reversed as daylight returns toward the springtime. The change in temperature does have a bearing on this process as well, but it’s largely the light. And the black tips of the weasels’ tails? They will draw a predator’s eye and cause them to miss, increasing their chance of survival in the winter. In some areas where the snow is less consistent, weasels have also adapted to wear patchy coats instead.

New Discoveries in Alaska: The Haida Ermine

Alaska is aptly named the Last Frontier. There are opportunities for continuous discovery here, and less than a year ago, researcher and biologist Jocelyn Colella – who after years of study, and comparisons of ermine skulls – she discovered a new species—the Haida ermine. As it is an isolated environment, Prince of Wales Island is ideal for species to evolve and adapt to the localized conditions.

How was this so? Picture a very different landscape to the one that we know and love now. Over the last 1.75 million years, our planet saw at least ten ice ages. There were natural cycles of warmer and cooler periods as vast glaciers expanded and contracted. Over the course of this incredible age, known as the Pleistocene Epoch, various species were separated by glaciers and changing sea levels and isolated for tens of thousands of years or more. Areas of the outer coast of Southeast Alaska were refugia – regions where isolated species thrived. Black bears, brown bears, marten, grouse, and ermine survived there, developing in isolation from others of their kind. As time progressed, they became genetically distinct.

And so it was that the Haida ermine became distinct from its cousins, the least and short-tailed weasels. There is enough evidence to suggest that Alaska may harbour other unique subspecies as well.

So next time you’re wandering your local snowy byways, keep a keen eye out for weasel tracks. There’ll be four toe prints, oval-shaped, with a narrow, curved paw pad. It may be the only evidence you have of the furtive passing of these clever, tenacious, and incredible residents of Alaska.

References

Article on ermine & color change

https://www.akwildlife.org/news/species-spotlight-ermine-the-color-changing-weasel

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.