Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

December 2021

Weathervane Scallops

They see, they swim, they’re giant bivalves

The scallops looked awesome. Piled in a bowl on ice in the grocery store seafood case, the plump morsels of ivory-white meat were big as marshmallows. A bit more expensive, however: $32 a pound.

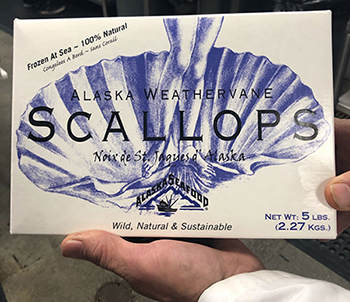

The friendly butcher in his clean white coat and mask said the price had gone up in recent months. He grabbed a five-pound box from the freezer. “Alaska Weathervane Scallops - 100% natural, frozen at sea.” They were harvested July 18 by the F/V Provider.

Weathervane scallops are the largest scallop in the world. Other scallop species are found in Alaska waters but only the weathervane – also known as the giant Pacific scallop – is commercially harvested here. Other scallops in our stores come from the East Coast and include the Atlantic sea scallop and the smaller East Coast bay scallops, found in shallower waters closer to shore.

Those East Coast fisheries are the largest scallop fisheries in the world – tens of millions of pounds of shucked meat compared about 280,000 pounds harvested on average in recent years (2012-2021) in Alaska waters. The Provider is one of only two boats currently fishing for scallops in Alaska; she and F/V Ocean Hunter are part of the same cooperative, Alaska Weathervane Seafoods.

“Most of Alaska’s scallops go to the white tablecloth market – high end restaurants,” said Tyler Jackson, a Fish and Game biometrician based in Kodiak.

Jackson analyzes data collected by onboard observers, who work alongside the fishermen, sampling and monitoring the scallop catch and the bycatch as it comes on deck. That’s part of the data he uses to help Fish and Game manage Alaska’s scallop fishery - seafloor dredge surveys provide additional insights, as does harvest data from fishermen. A wealth of information is gathered, but more is needed - and its value increases over time.

“There’s a lot we don’t know about scallops,” Jackson said. “We’re building data streams. They’re just young. If we have enough data, we can develop a stock assessment model and get a better idea of stock status.”

Management requires preseason and in-season information as well. Guideline harvest levels are set before each fishing season starts. Because crabs may be caught along with the scallops, crab bycatch limits are set, and fishing can be closed when crab limits are met. Learning scallop’s growth rates, size at maturity, and age is also key to assessing the resource.

A scallop’s life

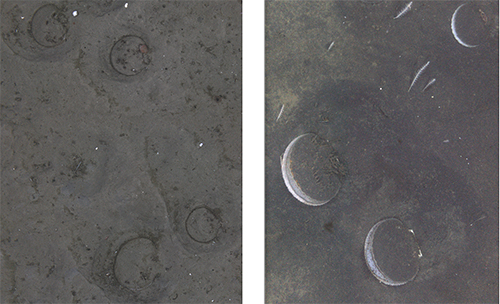

Weathervane scallops nestle in mud and sand and are fished mainly between depths of 120 to 400 feet. Fish and Game biologist Ryan Burt manages the onboard observer program and the dredge survey program, which provides a direct connection to the variety of life in the scallop beds. He was also involved in the CamSled program in the past – which provided an up-close look at the seafloor and its life. Over the course of participating in several surveys using the CamSled, he observed scallop behavior.

“They sit on the bottom, half open, filter feeding,” he said. “They’ll pump and make a depression for themselves in the sediment. Fishermen call it ‘pumping down,’ they make these divots and nestle down, hide out from the current. I’ve also seen them up on the edge of their little nest, opened up and feeding, facing into the current.”

If they pump down far enough into the seafloor sediment, they may avoid the dredge. “Fishermen think they settle down into the sediment,” Burt said. “There are times when the tide is slack they will catch scallops, and when the tide turns catch rates go down, in the same places.”

Scallops can do more than just shift their position, they move around throughout their life. “There may be areas of the beds that are nursery habitat, and they move later,” Burt said. “It’s not clear how much they move in a season, but they are definitely capable. They are not sessile.”

Scallops are bivalves like clams and mussels, but unlike sessile mollusks that live buried or fastened to a substrate, scallops can swim by rapidly clapping the two valves of their shell. It’s good enough to escape the clutches of a starfish, but probably not an octopus. Their large adductor muscle, the “quick” muscle, enables that swimming. That muscle is what I saw in the seafood case and it’s what we think of as a “scallop” in our dinner, although it is only about ten percent of the animal.

Scallops can also see, another unusual talent for a bivalve. Tyler Jackson said if you put your hand in a tank of scallops, they close up. A weathervane has about 200 eyes, lining the edge of the mantles. They’re usually described as primitive photorecepters, but scientists are re-thinking that.

“They’ve looked at the eyeballs themselves and they are more complicated than we thought,” Burt said. “They might be seeing better than shadows or contrast. Scallops have been around for over 200 million years, and personally I think they can see better than people might generalize.”

Catching scallops

Scallops are caught using New Bedford style scallop dredges that average 15-feet wide and weigh about 2,600 pounds. A frame provides a rigid, fixed dredge opening to which a steel ring bag (made from 4-inch rings linked together) is attached to collect the scallops as the dredge is towed behind and below the boat. Most small scallops pass right through the bag.

How the dredge is fished depends on the scallop bed and the conditions. “All captains do it differently,” said Jim Stone, who works with the Alaska Weathervane Scallops cooperative and the Alaska Scallop Association, the trade organization. “You have to get it at the right angle, with the right engine speed, the right amount of cable; are you with the current or against it, sideways to it – it takes a lot of expertise. If the fishing is hot they may pull it up in half an hour, usually not more than an hour.”

The Provider has a crew of 12, as well as the onboard observer. Crew members shuck, sort and clean the scallops as soon as they are caught, they are packed into boxes like the one I saw and frozen at sea within hours. The season can be long, July through February, but it’s often closed by October. Both the Provider and the Ocean Hunter are homeported in Kodiak.

Burt, who manages the observers, said they work onboard the fishing vessels for months at a time. He knows the drill - he worked out of Dutch Harbor as a fishery observer himself. “Some observers work the entire season, but they can only spend up to three months on any one boat per year,” he said. “That’s the maximum allowed, 90 days per year per vessel.” One observer is typically onboard July through September, another in the fall, but there are breaks to avoid storms and resupply.

“Scallop fishing is a lot of work, it’s hard work for the crew,” Burt said. “They do come in for weather, food and fuel, to swap observers, deal with mechanical breakdowns, and to offload. That’s a cool aspect of this. It’s not like commercial salmon fishing where you have to catch the fish before they enter the rivers. The scallops are in their beds all year round so scallopers can take their time if they need to.”

Observers record the size and weight of scallops caught, and take numerous samples. They document how long the dredge was fishing and biomass caught, the ‘catch per unit effort.’ “That’s an index of relative abundance,” Jackson said. “If the fishing conditions year to year are equal, then the catch rate should reflect abundance.”

Biologists are taking an updated look at scallops’ size at maturity. There’s not a formal size limit, but weathervane scallops are considered harvestable when their iconic seashell is about 4-inches high and the animal is about 4-years-old – smaller scallops are generally returned to the water alive. Stone said scallops in the 6-7-8-inch range are pretty typical, and shell height can reach 12 inches. That would indeed be a giant Pacific scallop.

Scallops live well into their 20s and as old as 28. It’s important to know that there are plenty of mature, reproducing adults in the population. Scallops are aged by examining the outside surface of the top shell, which records growth patterns that can be counted like the growth rings in a tree.

Dredge surveys provide critical information. A commercial scallop fishing vessel is chartered to conduct surveys. They’re similar to actual fishing in harvest areas, but the dredging is done in a systematic manner that allows biologists to estimate large-scale scallop abundances, round-weight biomass, and age and size distributions. They yield samples for testing – and not just scallops. Because crabs, sea stars and other creatures share scallop habitat, the surveys offer insights into seafloor life, which benefits other researchers and marine biologists.

Meat weight is important. It doesn’t always correlate to the size of the scallop shell and varies between areas, time of year and ocean conditions. “We see changes in meat weight year to year, and that’s the currency of the fishery,” Burt said. “We’re collecting a lot of data and trying to understand why meat weight is fluctuating.”

Scallop meat can be fat and plump or small and skinny. Fishermen grade the meat by size – the scallops I saw were in the range class of 20 to 30 per pound. Small scallops are 40-60/pound, really big ones would be 10-20/pound.

“Managers need to know size of the meat,” Burt said. “As a rough guideline I say 25-30 scallops to a pound of meat. So, 280,000 pounds of meat is roughly seven million animals. That’s another transition we’d like to make, incorporating numbers of scallops with pounds of meat weight.”

Burt references 280,000 pounds because that’s been the average harvest in recent years. Harvest was higher years ago when more boats were fishing – the 20-year average from 1994-2015 was close to 540,000 pounds. This is all well below what managers established in 2012 to be the “overfishing level” of 1.29 million pounds of shucked scallop meats.

Another significant move to prevent overfishing was to limit the number of boats. The fishery is jointly managed by the state and federal government. In the early 1990s, in response to an influx of East Coast fishing boats, federal managers implemented a limit; now eight vessels hold permits. Those permit holders created a scallop fishing cooperative in 2000 and some members and arranged for their shares to be caught by others in the cooperative. In recent seasons, only the two aforementioned vessels have participated in the fishery.

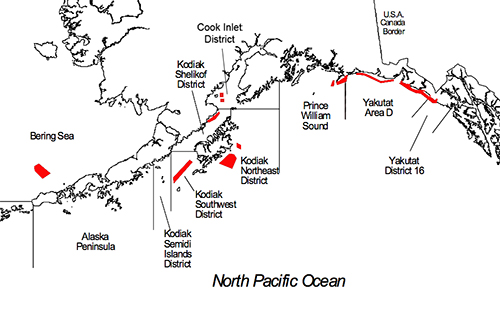

Where are the beds?

Virtually all Alaska scallops come from two regions – around Kodiak Island (particularly in Shelikof Strait between Kodiak and the Alaska Peninsula) and about 500 miles east of there in the Gulf of Alaska waters off Yakutat. “Those two areas are huge, and there are a whole bunch of beds. The fishermen move around,” Burt said.

“The fishermen are tending the bottom and managing themselves, it’s nothing official,” Stone said. “They talk with each other, and some beds are left alone for a couple of years. They rotate through areas.”

“The Kodiak area is more productive than Yakutat, and scallops get bigger at a younger age. They get bigger, faster,” Burt said. “Yakutat scallops might be half the size at the same age.” Biologists would like to understand why those two areas are so different.

Scallop numbers on a bed vary year to year. Shelikof Strait near Kodiak is one example. In 2015 fishermen harvested 30 pounds of meat weight per dredge hour of fishing. That’s low, and in response, Fish and Game reduced the quota. In July and August of 2021, fishermen harvested 107 pounds of meat weight per dredge hour on those same beds. “That’s a dramatic swing there,” Burt said. “Now we’re ratcheting back up the quota. Something happened and they came roaring back.”

Where did the scallops I found in the grocery store come from? Burt checked where the Provider was fishing on July 18th: off the southwest end of Kodiak Island.

Those aren’t the only scallop beds in Alaska waters. There are productive areas in Cook Inlet, Prince William Sound and the Bering Sea that have not been fished for a while. The scallop cooperative has a third boat, the F/V Polar Sea, that used to fish scallops the Bering Sea and is now geared up for other fisheries.

“Weak Meat” in the Bering Sea

During the 2014/15 season a problem emerged in the Bering Sea fishery. Fishermen were catching the same number of scallops as in past, but when they’d shuck them, the meat was sticking with the guts. Normally it’s quick and easy to open a scallop and pop out the meat separate from the organs. But the retention of the muscle seriously interfered with shucking; rather than sort through the whole mess to pick out the actual meat, they’d toss it overboard and move on to the next scallop. So, they were harvesting half the meat weight. Plus, the meat was smaller and strange. Observers collected samples that were later sent to the Anchorage pathology lab, and Fish and Game pathologist Jayde Ferguson identified a parasite.

The culprit was an Apicomplexan parasite, a one-celled protozoan. It’s known to scallopers in the Atlantic; they call the condition it causes “grey meat,” in Alaska we call it “weak meat.” It gives the meat a darker grey color and an abnormal texture, making it unacceptable for marketing. It affected the Atlantic Sea scallop fishery, which has since recovered, and contributed to the collapse of scallop fishery in Iceland in the early 2000s.

A subsequent survey of Alaska scallop beds revealed the same parasite across the state, at varying levels. Ferguson recently published a paper on the topic in the Journal of Invertebrate Pathology and wrote that fishermen report that the Yakutat area typically has some percentage of dark meats - which fluctuates considerably each year. In contrast, dark meats are almost never found in the Kodiak area.

A small amount of scallop fishing occurs in the Bering Sea, partly to provide monitoring. In the 2020/21 season, as a result of the weak meat issue, rising fuel prices, and COVID, scallop fishermen moved out of the Bering Sea to focus on areas closer to Kodiak.

The co-op will likely return. Stone thinks the parasite is part of a bigger picture. “We’ve seen this before, in Yakutat, there were beds you couldn’t fish at all, and now those beds are producing these beautiful white meats,” he said. “I’m not sure what to point the finger at, what makes them go through that kind of cycle. It’s in perfectly healthy scallop beds and it’s not affecting them negatively.”

The Market

JIm Stone remembers personally bringing Alaska weathervane scallops to restaurant kitchens to get them on the radar.

“We were not well known for a long time in the Pacific Northwest or even Anchorage,” he said. “We used to sell mostly in the Netherlands and into France, but we haven’t sold there for five or six years. Now so many restaurants here know about them and want them, especially in Portland and Seattle and Anchorage. We have no problem selling them right here at home and don’t need to sell overseas and deal with all that extra work.”

Online retailers selling frozen seafood through their websites have come to represent a good chunk of business, Stone said. “So many have popped up in recent years, and most are small businesses, some are selling Alaska only seafood.”

Big scallops get a better price – Stone said they don’t taste better than smaller scallops but chefs tell him they like their presentation. Alaska scallops are recognized as a premium product, but the huge Atlantic fishery sets the prices.

“The price of weathervane scallops tracks closely with price of the East Coast sea scallops,” Burt said. Prices have gone up due to market demand and I’d also guess inflation - like a lot of other stuff lately.”

Stone said demand has definitely gone up. He said when the pandemic hit and restaurants closed, things looked bad. But as seafood economists have noted, after an initial decline, seafood sales went up.

“People cooking at home started getting fancy instead of just eating macaroni and cheese,” Stone said. “It turned out demand was high for online and retail sales in stores, and when the restaurants opened back up, it stayed up. It worked out fine.”

How does Stone recommend cooking scallops?

“Seared. Definitely best.”

More on Scallops

https://vimeo.com/668346265 - Biologist Jessica Glass offers a quick, insightful look at Alaska's Weathervane Scallop fishery. Scallopers, fishery managers and biologists provide insights. 5:30 min video.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.