Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

May 2022

Good News for Alaska Bats

Wildlife biologist Karen Blejwas has been studying bats in Southeast Alaska for close to a decade. Her focus on the flying mammals was prompted by a threat that’s proved tragic for bats in the East.

Millions of bats have died in eastern North America in the past decade, victims of a fungal disease known as white-nose syndrome. Little brown bats in particular have succumbed, and these are also the most common and widespread bat in Alaska . The disease first appeared around 2007 in the Northeast and by 2013 had spread to the Midwest. It’s now found in 38 states and seven Canadian provinces; it’s been detected in the Pacific Northwest but so far, not in Alaska. Research by Blejwas and her colleagues suggests Alaska’s bats will fare much better than their eastern counterparts should the disease arrive in Alaska.

“Little brown bats are found across North America, but it’s amazing how different their ecology is in the West,” said Blejwas, who works with Fish and Game's Threatened, Endangered and Diversity (TED) program. “When I started working with bats 10 years ago I was shocked at how little we knew – not just in Alaska, but in the West. We’ve been finding things nobody knew, and I love that.”

Little brown bats belong to the genus Myotis, a group of common, small, insect-eating bats. The little brown bat is found throughout much of Alaska; a half-dozen other species are found only in Southeast. These include California myotis, long-legged myotis, long-eared myotis, silver-haired bat, and the occasional Yuma myotis. Among other recent discoveries, researchers have learned that one Southeast bat, Keen’s myotis, isn’t even a species.

“It’s not a separate species – it’s now recognized as the Western long-eared bat,” Blejwas said. “Looking at the genetics, morphology and acoustics, it’s indistinguishable in all respects from the long-eared.”

The acoustics she refers to are the “signature” of the bat’s echolocation call. Bat detectors not only render the ultra-high frequency calls audible to our ears, they can create a graphic representation that can be compared to other bat calls.

Passive bat detectors are set up in good bat habitat and monitor bat activity, helping biologists learn when bats emerge from their roosts and forage, when there are lulls in their activity, and what species are flitting about on those relatively warm, buggy, not-so-dark Alaska summer nights. They are checked periodically and the data is collected. “Active” detectors – in the form of volunteer citizen scientists equipped with listening and recording devices - also contributed valuable insights, driving routes in a number of Southeast communities in summer months in recent years.

Why is white-nose syndrome so deadly to some bats?

Most insectivorous bats hibernate in the winter. Their body temperature drops to just a degree or two above the ambient temperature and their metabolism slows, which reduces the energy required for lasting out the winter. Researchers have learned that lower temperatures are better, and 2 degrees Celsius is ideal. However, this also suppresses the immune system, which makes them vulnerable to a disease like white-nose syndrome.

Biologists refer to the places where bats hibernate as hibernacula. Little brown bats in Eastern North America migrate to specific locations for the winter and hibernate in caves and mines, in huge groups. They used to be huge, at least.

“Sixty percent of the caves had more than 100 bats,” Blejwas said. “Many had tens of thousands. Those large colonies resulted in high mortality and steep population declines. Eastern little brown bat populations have declined 90 percent.”

The disease affects bats during hibernation and spreads between bats in these large, tightly packed groups. Bats with mild cases recover in spring when they emerge from hibernation and become active, but most bats don’t survive the winter.

We think of these bat-filled caves as stereotypical, but it’s not universally true.

“We developed a dogma that bats hibernate in caves and mines, because they’re accessible and visible in those places, and that’s where they were mainly studied in the past,” Blejwas said. Researchers have learned in recent years that what little brown bats do in the East isn’t necessarily what they do in the West. Bats in the West don’t use mass hibernacula.

“Even when caves and mines are available, they don’t use them,” Blejwas said. “Their hibernation needs are met by crawling into interstitial spaces between rocks in talus fields, in a tree rootwad or a stump. Why fly a couple hundred kilometers to a cave when you can fly three kilometers up a slope and hibernate there?”

A decade ago, it wasn’t known if Alaska bats hibernated locally or if they migrated to warmer locations. Evidence indicates they stay close to home, which means they’re less likely to pick up the disease from somewhere else and bring it to Alaska.

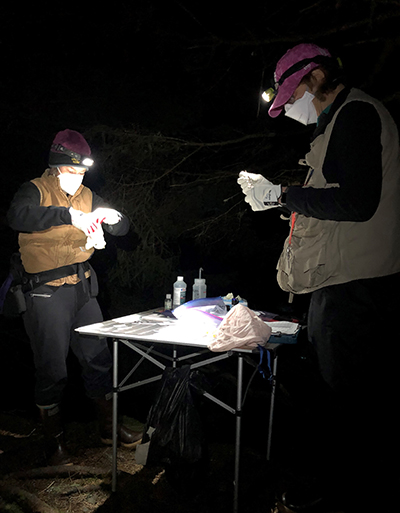

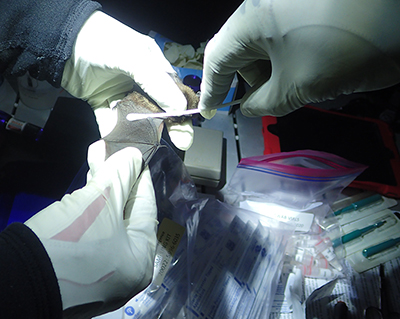

Researchers used mist nets to catch bats in the spring, summer and fall. Fish Creek on Douglas Island proved to be a good spot for mist-netting. Blejwas and her colleagues equipped some bats with tiny radio transmitters, and tracked them to roosts and (in the fall) to hibernacula in the same general area where they are active in summer. For bats in the Juneau area, that’s Douglas Island and nearby Admiralty Island.

The news is good because a crack in a rock, or between rocks, doesn’t accommodate many bats. Southeast Alaska bats – in fact little brown bats all across the western U.S. – hibernate in small groups, alone or in pairs, so bats are much less likely to transmit the disease to each other.

More good news

White nose fungus thrives best at temperatures close to 12 degrees Celsius (54 degrees F). The rootwad cavities and rock crevices where Alaska biologists found bats hibernating are much cooler, averaging just 1 degree C (about 34 F), conditions much less favorable to the spread of the disease and its effect on a bat that might get infected.

Bats in the East are hibernating in caves that average close to 7 degrees C (44 degrees F) – close to the optimal temperature for the fungus. Blejwas said that a study in the Eastern U.S., researchers deliberately lowered the temperature of a cave of hibernating bats to see if it would improve survival – and it did.

“Studies show hibernacula that are colder contribute to higher survival for bats,” she said. Hibernating bats are vulnerable to dehydration, so they seek out humid or damp hibernacula. “The coldest and wettest conditions had highest survival. Our hibernacula are very cold and 100 percent relative humidity, so very wet.”

That’s counter-intuitive – we tend to think of fungus thriving in damp environments. That’s largely true, but there’s a twist.

“Think what happens in a cold and dry environment,” Blejwas said. “Researchers believe the fungus ends up penetrating deeper in tissue because it needs moisture from the tissue. So even though it grows faster in cold and wetter conditions, it doesn’t do as much damage to the bat, it’s on the surface of the skin and doesn’t penetrate as deeply.”

What Next?

Bats emerge from hibernation in the spring, and in early April Blejwas was already seeing some bats emerging.

“There’s some activity at the Fish Creek detector,” she said. “It’s a month-long process, and the majority won’t be emerging until May. Reproductive females tend to emerge first. If they can emerge early and get the egg fertilized, start gestation, and have pups earlier, that gives them more time in summer. That’ll give the pups an edge for their first winter, they’ll learn to fly earlier, put on weight for their first hibernation season. Males often emerge quite late.”

Bats captured in mist nets and released provided insights into the sex ratios. “Almost all the bats we caught in the spring were female, that wasn’t the case in the fall, at Fish Creek,” she said.

While there’s a bit more bat-catching to be done, most of the work now is preparing for publication.

“We’ll probably do one trapping session to swab for white-nose syndrome, maybe one or two nights,” she said. “We’re winding down the bat work now. The focus is on writing up the results, and publishing all the data collected over last ten years.”

Although Alaska’s little brown bats aren’t migrating, there are other vectors for the spread of the white-nose fungus, aptly named Pseudogymnoascus destructans.

“A plane from Kentucky landed in Anchorage recently, with a live bat as a stowaway,” Blejwas said. “That’s a method of spreading white-nose syndrome, if it was infected.”

A Bit About Bat Babies

Blejwas’ reference to female bats “getting the egg fertilized” is not a comment about mating. Bats mate in late summer, during a seasonal social gathering known as swarming. Lots of bats in an area (and this can be millions of bats in some places) gather near roosting sites that also serve as hibernacula. Swarming is in part preparation for hibernation, possibly to teach the young-of-the-year where hibernacula are located, and it’s also an opportunity for mating. Southeast Alaska bats don’t swarm in huge numbers, but in small groups.

After mating in the fall, a female bat stores the sperm and becomes pregnant in the spring after she emerges from hibernation. A single pup is born in June or early July after a two-month gestation period. The pup nurses on bat milk for about three weeks, then learns to fly. Mother bats form large maternity colonies during the summer months and roost together. Bat researcher Michael Kohan counted more than 1,000 female little brown bats emerging from a maternity roost in the Mendenhall Valley in Juneau, popping out in twos and threes over a 45-minute period at dusk on a July evening.

The maternity colonies break up in late summer prior to swarming. By mid-to-late September the insects are gone and the bats tuck in to their hibernacula for winter.

Riley Woodford is the editor of Alaska Fish and Wildlife News and produces the Sounds Wild! radio program.

More on bats:

A motion triggered camera at a roost, one of the known swarming sites, captured bats flying in circles around the entrance.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.