Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

February 2023

Wood Bison Restoration in Alaska

2022: A Year of Progress

A storm to remember

On December 30th of 2021, a relatively warm, anomalous weather system moved through Interior Alaska, particularly impacting areas around Fairbanks, Healy, and Delta Junction. It snowed close to a foot, rained for 24 hours, the rain froze into a thick ice layer, and then another foot of wet snow fell on top of the ice. Some areas experienced even higher amounts of snowfall from the storm.

In the Fairbanks area around the regional ADF&G office where Wood Bison Project biologist Tom Seaton works, the storm resulted in a permanent ice layer of variable thickness (1-1.5”) that remained in the snowpack for the rest of the winter in affected areas. Wildlife in parts of the Interior had a particularly difficult time, with some localized populations of moose, caribou, and sheep declining as much as 40 percent.

Thick ice layers coupled with almost record snow depth made movement difficult and energetically costly for animals like moose, caribou, sheep, and bison, while also trapping food resources beneath an impenetrable barrier in the snowpack. When snow is soft and ice-free, ungulates can scrape, sweep, or dig for food beneath the snow, frequent areas with windblown or shallower patches of snow, and/or move easily between foraging areas.

When the storm in late 2021 was at its worst, Seaton worried that the severe weather might create ice layers in the snow that could make life difficult for bison in the Innoko.

Lower Innoko and Yukon rivers herd in the winter of 2021-22

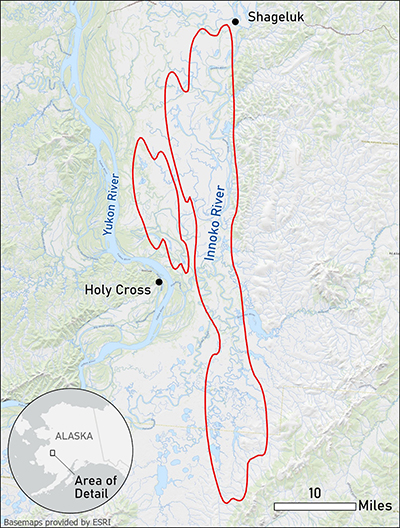

On April 3, 2015, a large group of wood bison jogged across frozen Innoko River towards the sedge and grassland meadows of western Interior Alaska, not far from the community of Shageluk. In late March, 100 cows, calves, and subadults were trucked and flown to the Innoko area and held in temporary pens until their release a few days later. In May and June of the same year, 30 bulls were trucked, barged, and released in the area with the rest of the bison in the Innoko. The Lower Innoko and Yukon rivers herd is the first in Alaska since the extirpation of wood bison in the state around 1915, and the only wild wood bison herd in the United States.

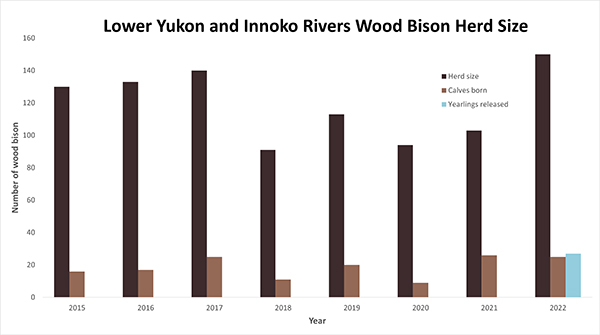

Since 2015, the herd has had ups and downs. In the early summer of 2022, the wild herd, through survival and reproduction from the original release, was still smaller, at 123, than the original introduction of 130 individuals. Despite the lack of overall growth, this herd grew year to year in five out of the seven years in the wild. Population fluctuations are not uncommon for wild ungulates, especially in response to severe weather. The two years of decline, 2018 and 2020, are attributed specifically to ice layers in the snow. Additionally, in 2020 the snowpack melted in mid-May, a full month later than normal. Bison in Alaska seem to handle cold and snow well if there are no thick ice layers to prevent them from getting to their food over the winter.

“We are learning that these ice layers in the snowpack are the most significant source of mortality for bison in Alaska," Seaton said.

Through reports from locals in the Innoko and a radio tracking flight in January, Seaton was able to keep tabs on the herd. He was able to directly assess the condition of bison when he flew to the Innoko to check on the herd and place several new radiocollars on individual bison in February.

In fact, the warming and rain that created such difficult conditions in other parts of the Interior yielded different results in the Innoko. A full week of rain was enough to melt most of the snowpack in the area bison were wintering without leaving an obstructive ice layer. The snow on the ground in February was soft and ice-free, and the bison were in the best winter body condition observed since their release in 2015. In fact, Seaton described the adult bison as “in phenomenally good body condition and extremely fat” when asked what stood out to him after returning from the trip.

In addition to finding healthy adult bison, Seaton also found a large cohort of calves doing well – he found 26 surviving calves from the 2021 crop of 26 calves observed just a month or two after being born. “Having 100 percent survival of any population of young-of-the-year wild animals in Alaska from birth to mid-winter is very uncommon,” Seaton emphasized.

Previous introductions of other species in Alaska have shown that it can take a decade or more for a population to gain its footing in a new location. As natural selection works through a population, surviving individuals are presumably better adapted to their new environment, increasing the chances of long-term success for the population.

While the Lower Innoko and Yukon wild herd is considered established and successful after seven years in the wild, the Lower Innoko-Yukon rivers area has recently had more variable winters with wetter, snowier, and sometimes icier conditions. Rain-on-snow events are becoming more common in Interior Alaska in general, and the resulting conditions can be detrimental for wildlife. For wood bison in the Innoko, ice layers have been a problem in only two out of eight winters. More often, ice layers have either never formed, or if they do, the weather has warmed enough to subsequently melt them off.

Adding young wood bison to the Lower Innoko and Yukon wild herd

In March of 2022, a collaboration between ADF&G and Elk Island National Park in Alberta, Canada brought 40 bison calves from Canada across the border to Interior Alaska by truck. They lived at the Robert G. White Large Animal Research Station (LARS) from April to July, while biologists monitored their growth and weight gain, conducted health checks, and eventually separated the bison into size classes. Ultimately, 28 of the largest calves were identified for release in the Lower Innoko and Yukon rivers area, to join the existing wild herd.

On July 17, the now yearling bison were loaded into four specialized steel shipping containers, placed onto trucks, and driven to a barge in Nenana. The barge then traveled the Tanana, Yukon, and Innoko rivers. The young wood bison were finally unloaded into a temporarily fenced soft release pen about 20 miles outside of Shageluk. Community members from Shageluk and Holy Cross had helped to construct the temporary pen earlier in the summer.

For the following two weeks several ADF&G biologists and technicians camped with the bison near the soft release pen, waiting for wild bison from the Lower Innoko-Yukon herd to connect with the new yearlings through the fence and become acquainted. It was important for the captive yearlings to mix with wild bison before they were fully released to provide them with the best possible chance to permanently join the existing herd. In early August, biologists opened the gates and the yearlings walked out of the pen.

Seaton says, “It was a great challenge to try to connect 28 yearlings to 100 wild bison within 1,500 square miles of habitat. We used all our knowledge about bison social structure, behavior, and historic movements to make the connection.” Intensive planning, a lot of hard work, and a bit of luck made it a success – radiocollar data indicates that the yearlings have remained with the herd.

Counting wood bison

How does ADF&G know if a wild bison herd increases or declines? One tool that can help is radio collars with both VHF radio and Global Positioning Systems (GPS) satellite signals. Radio collars are placed on animals throughout groups within the herd. GPS signals allow biologists the ability to track individual bison behavior and movements remotely. VHF radio signals helps staff locate bison from a plane during surveys with minimal search time, which is especially important given that the wild wood bison herd ranges over roughly 1,500 square miles of remote habitat in Interior Alaska.

ADF&G employs an ultra-high resolution camera system that is mounted in an airplane to photograph and count caribou (for more, see our video about conducting photocensus surveys of caribou herds: Counting Caribou), and Seaton has also found that it works well for wood bison. Photocensus efforts usually occur in mid-summer, after calving has completed for the year.

“Typically, in late June, the bison are gathered together in two to four large post calving groups, making an accurate count of the herd feasible,” Seaton said.

Calves are also easy to identify in mid-summer – they are an orangish-reddish-tan color distinct from the dark brown of adults. An accurate calf count is important for monitoring herd growth and the age composition of the herd. Another advantage of conducting the photocensus near the summer solstice is that flying surveys is much easier when daylight is nearly unlimited. However, in the summer of 2022, wildfire smoke was too heavy to get good photographs, delaying the survey.

Bison behavior changes with seasons, according to Seaton. In November, the bison were in many smaller groups, which made getting a complete count more difficult. Near the winter solstice, there is also only about five hours of daylight to fly surveys.

Fortunately, logistics and weather aligned on November 28th, allowing Seaton and ADF&G staff one day to survey. They found 19 groups of bison, from single individuals up to a group of 52. Given limited time to search for uncollared bison, Seaton suspects there were at least a few bison they didn’t find. The crew found 25 of 26 calves from 2021 that had made it to 17 months old, and 25 new calves from the summer of 2022. Between natural growth and the addition of 28 yearlings this summer, the Lower Innoko and Yukon rivers herd expanded from a minimum count of 103 bison in 2021 to 150 in 2022.

Currently, the Lower Innoko and Yukon rivers herd is around 51 percent calves and yearlings, which indicates that the herd has high potential for future growth. Large cohorts of young animals are the first step required for a growth spurt in wild populations of ungulates. The herd has been growing for two years. If this large young cohort survives to reproductive age (3 to 20 years), it will mean an additional increase in young cows producing calves, hopefully fueling a higher growth rate for the herd.

Wild wood bison in 2023 and beyond

Biologists will continue to monitor the growth of the Lower Innoko and Yukon rivers herd. Alaska also has a captive wood bison population split between two facilities - there are 10 remaining yearlings at LARS that were not ready for release this year, and 35 bison housed at the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center (AWCC). Most of the animals in both populations are eligible for release and can either augment the herd in the Innoko or help to establish new herds. ADF&G also has a long-term agreement with Elk Island National Park to get additional surplus young bison in 2024, 2026, and 2028, if available. The Lower Innoko and Yukon rivers wood bison planning team, composed of representatives from 28 different interest groups, met in 2022 and agreed on a new management plan that will be in effect from 2023 – 2028. The plan is currently moving through final review and revisions before it goes into effect this year.

“With the Lower Innoko/Yukon Rivers herd established and growing, it is time to focus on restoring more herds in the original range of wood bison,” says Seaton of the path forward. “Establishing multiple populations within Alaska is a significant step toward ensuring that this species survives.”

On the eastern side of the interior of Alaska, there is less snow, and snow is generally softer and drier than in western Alaska. Moose, bison, and sheep have more stable populations in eastern vs. western Alaska as a result. The Delta Junction plains bison herd provides an Alaskan example of a bison herd that has had consistently high productivity for more than 90 years, with a rare exception this past winter thanks to anomalous weather. The Aishikik herd just east of Alaska in the Yukon Territory also benefits from generally drier, less icy conditions. Both herds typically have annual growth rates of 15-20 percent.

While good habitat and snow conditions are important aspects to consider for the next release site, public support is just as important. ADF&G and the state of Alaska have received several written and verbal communications asking for wood bison restoration efforts to occur in parts of the eastern interior. With the knowledge that bison have the potential to be productive in eastern Alaska and that there is significant interest from the public, ADF&G is hosting three large public planning team meetings from January to March of 2023 that will include the Lower Tanana drainage, the Upper Tanana drainage, and the Yukon Flats.

Tom Seaton is realistic but also optimistic. “The future looks encouraging for wood bison,” he says, “Hopefully we can continue to restore this important resource for future generations. To take the next step forward, all we need is public participation in the planning process."

Jen Curl works for ADF&G in Fairbanks as part of the Wildlife Education and Outreach program, within the Division of Wildlife Conservation.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.