Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

May 2023

Salmon Shark Sightings

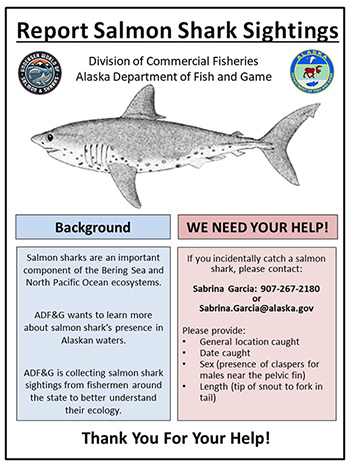

If you see or catch a salmon shark, Sabrina Garcia wants to hear from you.

Garcia is a marine research biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G). In summer you’ll find her on ships in the Bering Sea studying juvenile salmon, documenting their abundance, distribution, and diet. Typically, each summer a few salmon sharks are caught in surface trawls during salmon surveys and released unharmed. Garcia is making the most of these opportunities to add to our understanding of these little-studied predators.

“My job is 99 percent salmon, but the salmon shark research is pretty unique,” she said. “There’s so much to learn.”

She’s compiling reports of sightings around Alaska, and hopes to create an accessible database that includes shark locations, sex, date caught or seen, and size, to better understand salmon shark migration and distribution.

Sharks in general are poorly understood, which is a bit surprising, considering people’s general fascination with them.

“At some point in many people’s lives, sharks are their favorite animal,” she said. “Despite how iconic great whites are, and are one of the most-studied shark species, we still don’t know where the females go to pup or where they mate."

It’s challenging to study sharks, especially those that aren’t close to shore or present in shallow waters year-round. Research often focuses on commercially valuable species, which salmon sharks are not, but salmon sharks play a key role in marine ecosystems.

“They’re one of the top predators in our waters,” Garcia said. “And we need the top predators regulating populations of lower-level predators and keeping the balance in the ecosystem.”

She said that while people think of salmon sharks as primarily eating salmon, their diet is much more varied. Most studies of salmon sharks’ diet were conducted in summer when they’re feeding on concentrations of salmon. “It would be incredible to know what they eat outside summer months,” she said.

“We tend to see them in summer,” she said. “We know quite a bit less about where they are and what they eat in the non-summer months. It’s kind of a misnomer. They do eat salmon, but they also eat rockfish, dogfish sharks, squid, and many other fish species even when salmon are concentrated and abundant. Researchers pulled stomachs from salmon sharks in Prince William Sound, where there are large runs of pink and chum salmon, and of those salmon sharks, about 25 percent of their diet were species other than salmon.”

It gets really complicated fast, she added, because what they eat varies depending on the size of the shark, the season, and the region, but this is based on very few available studies. Salmon sharks are also preyed upon by killer whales.

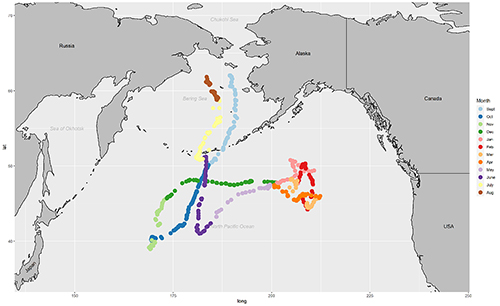

Biologists are learning more about where “Alaska” salmon sharks are and where they go, thanks to eight salmon sharks that Garcia and her colleagues have tagged with satellite transmitters in recent years. Sharks were tagged opportunistically during summer salmon surveys in the Bering Sea and North Pacific Ocean. The tags transmit the shark’s location whenever the tagged shark is at the surface. Six of the eight tagged sharks are still transmitting, including Lawrence, the first shark equipped with a transmitting tag three and a half years ago. Both Lawrence and Ada, the most recently tagged shark, were caught and released near St. Lawrence Island in the northern Bering Sea.

“Lawrence is my rockstar, he’s still transmitting,” she said. “The transmitters typically last three years, and he’s going on three and a half. He spends a lot of time at the surface, so we get a lot of good locations from Lawrence. He’s a good shark.”

Ada is a big female, almost eight feet long, tagged in September 2022. She’s covered more than 4,000 miles. “She’s currently just north of Hawaii. She swam a long way in the eight months since being tagged. The other salmon sharks tagged in Prince William Sound, all females, typically spend summer and early fall in Prince William Sound and the Gulf of Alaska, then over-winter off the coast of California, and come back to the Sound the following summer.”

Salmon sharks sexually segregate, and Garcia said most of the sharks in Prince William Sound are females, and sharks in the Bering Sea tend to be males. The male sharks tagged by Garcia and her colleagues were the first to be successfully satellite tracked. Marine scientists would like to know if there are one or two distinct populations of salmon sharks in the western and eastern Pacific, and if they mix.

“Some of the sharks we tag are traveling over 10,000 miles in a year,” she said. “While the tags give us great location data, they don’t tell us what they’re eating or why they go to the places they go. We don’t know where they are mating. We have an idea of where they go to have their pups, but that’s based on strandings along the west coast of the US.”

Salmon shark pups-of-the-year sometimes wash up on West Coast beaches, implying that they were likely born (pupped) somewhere nearby.

Reporting Sharks

Garcia has been soliciting reports of sightings and catches for almost three years now, and while salmon sharks are fairly common, reports are not. Even when government scientists catch sharks it’s difficult to get the information.

“Salmon sharks are caught pretty regularly in research surveys led by ADF&G and NOAA, but the information is hard to pull together in one place,” she said. “They are not a target species. People just want to get them off the boat as fast as possible because they’re super energetic. You’re trying to do research on some other species, like salmon or pollock, and you have this shark that’s all muscle thrashing around – the scientists just want to get it back in the water as quickly as possible.”

She has received a few reports from trollers from Petersburg and Homer, from trollers off Yakobi Island, and outside Sitka. She’s also been sent links to posts on iNaturalist and Facebook referencing sightings.

The ADF&G Facebook page, “The Undersea World of Salmon and Sharks” features salmon research and also highlights and updates the movements of the tagged salmon sharks that are cruising in the North Pacific and Bering Sea.

“A lot of times a friend will send a message, ‘Did you see this video of all these sharks in Kodiak?’ I usually get sent links to Facebook posts from people catching them or seeing aggregations near Kodiak or Chignik.”

Those aggregations are unpredictable and intriguing. “You’ve got fifty sharks finning at the surface in a bay near Chignik, and the next year they’re gone,” she said. “Where do they go year to year and why?

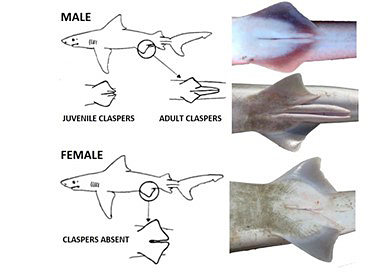

If you incidentally catch a salmon shark, please contact: Sabrina Garcia: 907-267-2180 or sabrina.garcia@alaska.gov. Ideally, please provide: General location caught, date caught, sex (presence of claspers for males near the pelvic fin), and length (tip of snout to fork in tail). Pictures are very helpful, especially of the underside of the shark, and she can determine the sex of the shark from pictures.

“Knowing the sex and length is super important because they exhibit size and sex segregation that is common in most shark species,” she said.

Because salmon sharks are endothermic (basically warm blooded) they are one of the northernmost sharks on the planet. One notable report came from Point Hope, in the Arctic on the Chukchi Sea about 200 miles north of the Bering Strait.

“A shark was caught in a subsistence gillnet, and that’s very far north,” she said. “Have they always been there? Is it normal to get sharks there? We need a baseline of information, many years from now we are going to want to know what was going on now so we can assess if things are changing.”

More on salmon sharks

Salmon shark tagging in the Bering Sea (2020 AFWN article)

Hot blooded predator: The Salmon Shark (2005 AFWN article)

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.