Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

July 2023

Seagoing scientists

safer at sea

Commercial fishing has long been notoriously dangerous. Seagoing scientists, and onboard fishery observers who work on fishing boats, face similar hazards. Bo Whiteside, a fishery biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game based in Kodiak, is making this work safer.

“We have a lot of seagoing biologists out here,” he said, “That includes shellfish, finfish, and groundfish research and management biologists.”

Whiteside manages the Shellfish Observer Program, which employs about a dozen crab and scallop biologists and up to two dozen contracted fishery observers based out of Kodiak and Dutch Harbor. While at sea aboard fishing boats, the observers collect important information about the fisheries that biologists use to make management decisions.

The ADF&G Westward Region extends safety training to all Fish and Game staff and observers working in waters around the Alaska Peninsula, the Gulf of Alaska, and the Aleutians and Bristol Bay, areas renowned for their fish - and dangerous conditions. While Fish and Game has several research vessels, many marine surveys are done aboard commercial fishing vessels that contract with the state. All the fishery observers are on commercial vessels.

Up until the 1990s, crab and halibut fishing were two of the most dangerous occupations in America. There was a “You have to go out, but you don’t have to come back” mentality, and some years, dozens of fishermen didn’t come back. Safety began improving with the Commercial Fishing Industry Vessel Safety Act of 1988, and by the mid-1990s, gear such as immersion suits, EPIRBs (emergency signal beacons) and life rafts were required on fishing vessels, and safety drills and first aid training were required for crewmembers.

“It used to be normal to not wear a personal flotation device (PFD), and there might have been just one or two people onboard that had training and they were the designated experts, but they didn’t regularly conduct drills with the crew,” Whiteside said. “When that was federally mandated, it really changed things, it became normal to have drills.”

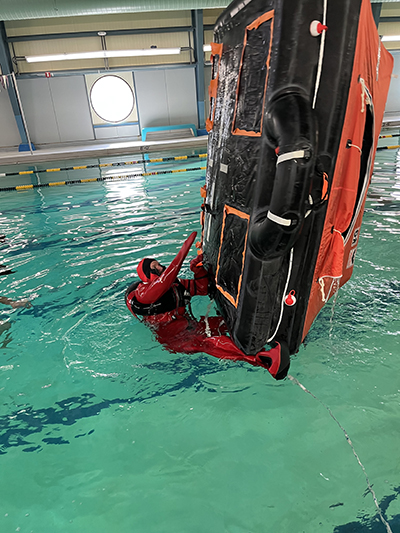

Whiteside collaborates with the Alaska Marine Safety Education Association (AMSEA), which teaches mariners how to use their safety gear, deal with emergencies, and assess risks. AMSEA is based in Sitka and has trained more than 200,000 people since 1985. The group works mostly in Alaska but also on all coasts around the United States. AMSEA provides hands-on training, putting trainees in survival suits and in the water; they light flares and extinguish fires, and do damage control. They have classroom sessions on cold water shock and hypothermia.

“I think the need is pretty great - if anyone is going out at sea, they need some kind of safety training, whether it’s through AMSEA or not,” Whiteside said. “We all know there are inherent hazards in anything boat based, whether you are in a skiff near shore or you are way out in the ocean. A lot of people know somebody who’s gone overboard, been on a boat that caught fire, or died at sea.”

Whiteside has been through a broad gamut of training himself, and also helps to train the trainers through AMSEA’s weeklong marine safety instructor training course (MSIT). He came to Fish and Game in 2016; prior to that he was a Program Debriefer and the lead marine safety instructor for the federal West Coast Groundfish Observer Program.

“In my previous position, I got MSIT certified in 2011, and since then I’ve had four re-certifications and refresher trainings, and they’re all a little different. I attended the marine firefighting academy in Oregon and aviation dunker training – escaping an aircraft, helicopter or fixed wing, that’s in the water.”

Most hazards that mariners encounter fall into four broad categories - person overboard, fire, flooding, and abandon ship. The training teaches individuals how to respond, how to recognize hazards leading up to an incident - and how to potentially prevent it.

“People really need to know how to operate a fire extinguisher,” Whiteside said. “And how to fire a flare – those things are pretty powerful, it’s a rocket projectile coming out of a tube, they have quite a kick to them. And handheld flares, people have no idea how much molten metal is dripping off the thing. What if you’re in a raft and holding that with all that slag coming off? Plus, you have to do this under pressure in an emergency.”

Programs are being developed to address specific hazards each biologist may face in different niches. “We can tailor our training to our group and its needs,” Whiteside said. “Some training is geared for people on vessels going really far offshore, where you are not going to have rescue coming in 30 minutes. Some is geared toward vessel operators.”

Whiteside said he’s been working towards developing a marine safety culture at Fish and Game and it’s gaining momentum thanks to support from Department leadership. Multiple staff have received their AMSEA Marine Safety Instructor Training certifications, and all sea going staff in the region (Region 4) are attending AMSEA sponsored Drill Conductor trainings, or similar training, prior to deploying on a vessel. This teaches the biologists and staff how to run the four primary emergency drills at sea.

“We have also just begun to conduct internal marine safety trainings with many more to come,” Whiteside said.

The sinking of the crab boat Scandies Rose, west of Kodiak Island on December 31, 2019, was particularly chilling for Whiteside. Two crewmembers barely survived, and five were never found. Whiteside said under different circumstances there would have been a fishery observer onboard at the time. “There wasn’t an observer on board, but there was a 20 percent chance there would have been,” he said.

He wondered if an employee of his program had been in that harrowing event, would they have been prepared? What kind of training would have made the difference between life and death?

When the National Transportation Safety Board finished the investigation of the Scandies Rose incident in 2021, NTSB Chairman Robert Sumwalt was quoted at the meeting when they announced their findings: “Commercial fishing in 2019 was not just one of the most deadly occupations in America, it was the most deadly occupation in America,” he said. “Commercial fishing had a fatality rate of 145 fatalities per 100,000 full-time employees. Compare that to the average of all workers, which is 3.5 fatalities per 100,000.”

The work is less dangerous than it was 30 years ago, but it’s still dangerous. Whiteside noted that the development of a safety culture, whether it is firearms, field based or out at sea, is an ongoing process. It’s also complicated by the seasonal nature of so much of the Fish and Game work.

“With the seasonality of our work, people come in and start a job and they might go out in the field the next day,” he said. “The logistical challenges have been difficult, but it’s something we have to place emphasis on working towards as we develop the culture.”

More information

NIOSH and commercial fishing safety

AMSEA and upcoming courses in Alaska

Coast Guard dockside vessel safety inspections

Surveillance and Prevention of Occupational Injuries in Alaska: A decade of Progress, 1990-1999

An excellent overview of the industry can be found here - Fatal Occupational Injuries in the U.S. Commercial Fishing Industry: Risk Factors and Recommendations Alaska Region (Looks at trends 2000-2009)

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.