Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

September 2023

Wolverines and Other Mysterious Mustelids

We woke to a chilly May morning in Chugach State Park. We were camping along Eagle River just a few miles from the river’s source, Eagle Glacier. Knowing it would take time for the sun to rise above the surrounding mountains and provide any warmth, a few in our group gathered and began our morning routine. Others remained in their tents, unwilling to rouse themselves from their sleeping bags. We lit camp stoves anticipating warm drinks and oatmeal, and the sound of the river and our stoves blended together.

Movement drew our attention. A dark brown body with a whiteish-gold stripe appeared across a nearby creek. A wolverine. The wolverine crossed the creek and walked just 50 feet from where we sat, still and staring. An instant later the wolverine walked out of view, back into the forest. We sat silently, hoping it might reappear. The forest was still, and after a few moments we were brought back to the sound of the stoves and the river.

Wolverines (Gulo gulo) are the largest terrestrial member of the mustelid family (Mustelidae), a group of mammals identifiable by their long, narrow bodies, elongated skull, and relatively small head. Mustelids are carnivorous mammals with sharp teeth and claws. There are eight species of mustelid in Alaska: fisher, mink, marten, wolverine, ermine, least weasel, sea otter, and river otter.

After breakfast I walked over to where the wolverine crossed the riverbed, excited for the opportunity to see wolverine tracks. The tracks stood out in the glacial sand; five toe marks with claws and a distinct impression of the pad. The tracks moved from the edge of the riverbank into the forest. The wolverine was traveling northwest along Eagle River, but there are many valleys and drainages for the wolverine to roam.

According to David Saalfeld, a research biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish & Game, wolverines have been known to travel up to 40 miles in a day. On average, females travel seven miles a day while males travel between five and 13 miles. Knowing this, the wolverine we saw along Eagle River could have traveled to virtually any corner of Chugach State Park later that same day.

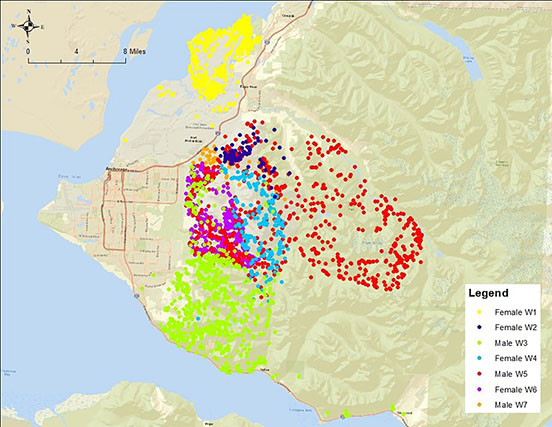

Saalfeld is leading a project to learn more about wolverine movements, habitat use, and population dynamics in Game Management Unit 14C, which includes the Anchorage area, Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson and Chugach State Park. To date, researchers with this project have collared 14 wolverines. Wolverines are trapped near Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson during the winter, and as the GPS collars indicate, they travel all over Chugach State Park. The GPS collars send the wolverines' locations at regular intervals, daily or several times a day, whatever the researchers set. The data enables them to track and map the animals movements and use of habitat.

Most wolverines live to be five to seven years old in the wild, but some are known to survive to 12 or 13 years old. Females rarely produce a litter of kits before they are three years old. Wolverines might have a litter of two to four kits in the spring, but by fall typically only one to two of the kits will have survived.

“Monitoring wolverine populations is important because there are many user groups interested in wolverines,” Saalfeld said. “Wolverines are prized not only by trappers but also wildlife enthusiasts.”

The map below shows the movements of seven collared wolverines Between January and March, 2023, each identified by color. Most of the animals have fairly distinct home ranges (many overlapping) and virtually all the movements are within Chugach State Park and Joint Base Elmendorf Richardson lands. Note that Male W5 (in red, ranging east to the Eagle River drainage) and Male W3 (green) tend to range much farther than the females. Note also that females W1 (yellow) and W4 (light blue) each made a brief foray south at some point before returning to their main areas of use in the home range.

Tracks in the snow

The following year I was skiing along Peters Creek in Chugach State Park on a cold but sunny day in March. Fortunately, it was midday and the sun had risen above the surrounding mountains providing some much-appreciated warmth. As I skied along the valley floor, I noticed a set of animal tracks paralleling my path. In areas where the snow was hardened by the wind the tracks were very clear. The size and shape of the tracks, as well as the location and time of year made identifying them straightforward. Wolverine tracks.

I skied alongside the tracks and followed their path. The tracks meandered a bit but traveled with purpose and efficiently navigated terrain features. Following animal tracks will never get old, and oftentimes tracks and game trails provide efficient routes through terrain. When it was time to part ways with the wolverine’s trail I wondered if this could be the same wolverine I saw the previous spring. What a journey that must have been.

More on wolverines

Stay tuned for the next issue of Wild Wonders Magazine that tells a story about another mustelid named Ferocity and follow along as she goes on her own journey. The issue will be available this Fall.

Alaska's Wild Wonders Magazine is produced by educators from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game's Wildlife Education program. It encourages participation in outdoor learning and conservation concepts across Alaska.

Alaska educators are welcome to request a FREE annual subscription.

Learn more and access digital copies of the issues 12 issues have been produced, featuring animal tracks, skulls, fur and feathers,bears, birds and more.

Wolverines: Behind the Myth (Alaska Fish and Wildlife News December 2014)

Breeding Wolverines (Alaska Fish and Wildlife News May 2016)

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.