Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

August 2006

The Alphabet Hills Prescribed Burn

For updated information on Alphabet Hills prescribed fire, please visit https://adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=habitatrestoration.wildlifehabitatenhancement May, 2020

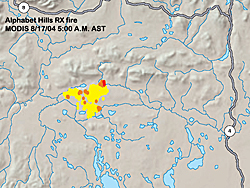

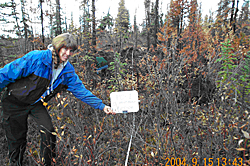

Like the Interior Alaska ecosystem, the boreal forest in the Copper River Basin in Southcentral Alaska is adapted to periodic wildfires. But wet weather conditions and years of fire suppression have deprived many areas of the natural burns that benefit wildlife and the forest. Land managers set a fire in one of these areas, in the Alphabet Hills northwest of Glennallen in August 2004, and biologists are excited to see the benefits of that prescribed burn. “Prescribed burns are a wonderful tool to turn back the clock on years and years of fire suppression,” said wildlife biologist Becky Kelleyhouse. “A lot of natural fires have been put out in the last several decades, to the detriment of the ecosystem. Though prescribed burns mimic natural processes, prescribed burning is an expensive tool, and these projects are very difficult to pull off.” It is well known that moose thrive in the early successional stages of the boreal forest, where willows are dominant. The new growth is beneficial to many wildlife species. In addition to the new shrub sprouts, fire promotes the growth of forbs and sedges, which are also used by caribou and grizzly bears during the summer. Kelleyhouse works for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game in Glennallen under Area Manager Bob Tobey. Tobey and other land managers in the basin proposed and first developed this prescribed burn back in 1981. Since then, weather conditions and the availability of work crews and other factors have been problematic. The burn was lit in 1982, in 1984, and again in 2003, all with no luck. Tobey’s famed phrase was becoming widely repeated: “Just how do you burn a sponge?” He had all but thrown in the towel, but longtime Glennallen Bureau of Land Management employee John Rego and Kato Howard of the Alaska Fire Service still held out hope. With a rewritten burn plan in hand (with a wider burn prescription window) summer conditions in 2004 proved ideal for ignition. Though weather conditions were perfect mid-summer, fire crews were unfortunately tied up fighting or monitoring extensive wildland fires elsewhere until August. “The Bureau of Land Management and the Alaska Fire Service made this burn happen after years of frustration and unsuccessful ignition attempts,” Kelleyhouse said. “They brought their skills and resources to the table, and were willing to wait till the time was right.” Kelleyhouse said that area residents were concerned about this fire, and there were a number of public meetings to address their misgivings. “People were very concerned about smoky conditions, as well as the fire getting out of control and burning cabins,” she said. “Hopefully people realize that having this burn has reduced future fire danger, and it was actually part of the current BLM fuels reduction program, which was specifically implemented to reduce the fire risk around communities in the Copper River basin.” Crews set the fire by dropping incendiary devices from helicopters. It took less than a day to light the fire and less than a week to burn the majority of the acreage affected before weather slowed the fire. In some areas, fire continued to burn away at the duff layer almost unnoticed, resulting in rootless shrubs and exposed mineral soil and rock. “The results were typical of what happens with wildland fire,” Kelleyhouse said. “Some areas were unaffected, or just lightly burned, and some were burned to the mineral soil. That’s what makes the mosaic – some kind of pattern to the burn based on soil moisture, vegetation, and wind.” The perimeter of the burn area included about 41,000 acres. Within that perimeter is a mosaic of different habitats that serve wildlife in different ways. Unburned areas provide cover, and the lush new growth that flourishes in the burned areas provides nutritious forage generally high in nitrogen and low in tannins. Snowshoe hares, sharptail grouse and the raptors and lynx that feed on them also benefit from the aftereffects of fire. The Alphabet Hills Burn was centered in the central part of Game Management Unit 13, which Kelleyhouse helps to manage. “This area is right past where four wheelers can reach, and it’s always been a moose refugia of sorts,” she said. “It’s also part of an active managment area. So, with lower predation and enhanced habitat in this area, we should see improvements in productivity and survival over the next few years. As good as the timing was on this burn, it was only a drop in the bucket when you consider Unit 13 has nearly 10,000,000 acres of moose habitat. This goes to show that habitat enhancement is not nearly as simple as one would like to think.” Using a burn severity map developed by Randi Jandt of AFS during the summer of 2005, Kelleyhouse and local BLM biologist Kari Rogers set up 30 vegetation monitoring plots within the burn with a grant from the Safari Club International. Both agencies are committed to monitoring the vegetation regrowth and wildlife use in the burn area. Kelleyhouse flew over the area in late 2005 and saw a number of moose using the new burn. Moose were not drawn to the area because of food – it was too early after the fire – but because the habitat had changed. She said the new openings have provided a place where moose have increased visibility and perhaps sense of smell because of altered, enhanced airflow, all aspects of an animal's habitat. Perhaps ironically, Kelleyhouse also observed a pack of six wolves in the burn on the same flight. “They too benefit from new openings in their habitat.” Kelleyhouse said the BLM has more acreage they hope to burn in the same area in the future. “The burn plan is still open,” she said.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.