Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

November 2006

Investigating The Decline of The Northern

Alaska Peninsula Caribou Herd

Caribou populations fluctuate naturally. But when the Northern Alaska Peninsula herd began spiraling downward more than a decade ago and not stopping, caribou hunters and Alaska Department of Fish and Game biologists became increasingly concerned.

The drop was dramatic – from more than 20,000 animals in the 1980s to about 2,000 today. Biologists were unsure what was causing the decline but guessed that predation, poor range, disease and parasites might be playing roles.

Hunting was reduced but the population continued to plummet. The population objective for the herd is about 12,000 animals.

A research project initiated by Fish and Game in 2005 aimed to collect data on the influence of nutrition, disease and predation on calf production and survival within the herd. The work is partially funded with special general funds provided by the Alaska Legislature to enhance game management efforts and is a collaborative effort by three Fish and Game biologists: caribou expert Bruce Dale, King Salmon area biologist Lem Butler and veterinarian Dr. Kimberlee Beckmen.

The Northern Alaska Peninsula herd ranges from King Salmon to Port Moeller. Butler said the herd is important for subsistence and hunters have taken a keen interest in research findings.

“Everyone is wondering when this herd will turn around,” Butler said.

The biologists also hope their work will help explain why three other nearby caribou herds are also showing declines.

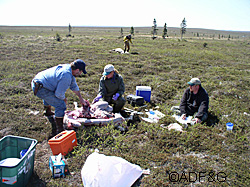

The project includes full health assessments of the caribou and detailed necropsy work by Beckmen. Cows and calves were captured and fitted with radio collars. The biologists then examined the nutritional status of the animals by measuring fat content and body condition and by looking at micronutrients in the blood such as copper and selenium that are important for immune system health and reproduction.

“We expanded it to make a true health assessment,” Beckmen said.

The biologists also tracked calves to determine mortality rates and better understand predation. They examined kill scenes to determine the cause of death, and took tissue samples to look for parasites.

Researchers soon learned that pregnancy rates had dropped by about 20 percent from the mid 1990s. Survival rates of calves were also lower than in other Alaska caribou herds.

They still didn’t know why, however.

The first clue that disease might be playing a significant factor surfaced in the late 1990s when former Fish and Game biologist Dick Sellers found a high rate of lungworm pneumonia among the herd.

“It appeared there was significant impact of disease on young caribou,” Beckmen said.

To learn more Beckmen began comparing the disease profiles from the collared caribou to 15 years of archived serum samples from the same herd and other herds across the state. That work has yielded a breakthrough discovery: Beckmen found that prior to 1999, the Northern Alaska Peninsula herd appeared relatively disease-free. But beginning in 2000, the blood work showed the presence of antibodies to Bovine Respiratory Viral Disease Complex.

Bovine Respiratory Viral Disease can cause difficulty breathing and even death in domestic cattle but its effects on caribou are not known.

Examinations of adult caribou also showed the caribou were heavily infested with parasites including Ostertagia, also known as the brown stomach worm. The parasite infects caribou as well as domestic reindeer and is known to reduce pregnancy rates and calf weights. A similar species in domestic cattle is a serious problem for cattle producers worldwide.

Beckmen said it was the highest parasite load that she’d ever seen in caribou. “It was pretty spectacular,” she said.

Biologists don’t know yet why the Northern Alaska Peninsula herd has so many health problems. Some diseases may have been introduced from other caribou herds or by cattle while the increase in parasites may have something to do with climate change.

But those are only guesses, Beckmen said. “It’s something to think about.”

Beckmen noted that the recent test results on the levels of essential trace minerals in the blood of the caribou reveal that they are not ingesting sufficient selenium and copper to maintain a healthy immune system compared to other caribou herds. This nutritional deficiency may contribute to their increased susceptibility to disease and parasites.

The studies also contained an experimental component designed to determine whether the caribou impacted by disease and parasites gave birth to weaker calves that were more susceptible to predation by wolves and bears.

The biologists captured and collared caribou and treated some with ivermectin, a medicine that kills parasites. A control group was not treated. The biologists are continuing to follow those animals to determine whether the animals treated with ivermectin had higher reproductive rates, and whether they gave birth to healthier calves with higher survival rates.

Beckmen said this kind of work is cutting edge and has never been done on a free-ranging caribou herd, although extensive studies in reindeer in Scandinavia have demonstrated the long-term beneficial effects of just one treatment.

So far conclusions have been difficult to make because not enough caribou have survived to make statistically significant comparisons. The adult cows treated with ivermectin do show healthier blood profiles and many tests are still being analyzed.

The biologists said the study is exciting because they are able to examine multiple possible causes for the caribou herd’s decline. In addition to understanding more about predator-prey dynamics, the biologists are also trying to learn about nutrition and habitat, and to understand the role of underlying health problems such as disease and parasites.

“A declining herd probably never has just one problem,” Dale said. “We’re doing our best to sort these things out.”

Elizabeth Manning is an outdoor writer and an educator with the division of Wildlife Conservation. Formerly a journalist with the Anchorage Daily News, she has extensive experience writing about the wilds of Alaska and outdoor recreation.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.