Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

November 2006

Lingcod

The Snake Tooth Fish

You’ve chugged out of the Seward Small Boat Harbor before the sun even peeked over the mountains. In the dim greyness of the typical Alaskan late summer morning, voices are quiet. The captain anchors up near a rock outcropping, and your 8-oz. jig is the first to zip through the cool blue to hit the bottom. A couple of reels up, and you’re set.

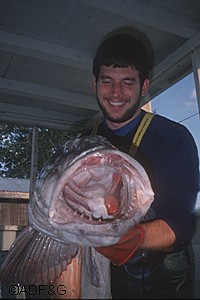

Still half asleep, you’re using the gentle rocking of the boat to bounce the jig, when your rod suddenly bends in half and starts to shake. After a short battle, captain, crew, and other anglers shouting instruction and encouragement while the rod tries to jump out of your hands, you haul up a fish with a huge, gaping mouth, and with huge flaplike gill covers. It looks like another fish’s giant head has grown out of a long, skinny, mottled rockfish. The mouth is so large, your 8-oz. jig looks like a size 10 trout fly. You’ve just caught a lingcod, whose scientific name, Ophiodon elongatus, means “snake tooth”

“Lingcod are attractive to recreational anglers mostly because they’re big, and they’re tasty, although a lot of anglers release them,” says Scott Meyer, Southcentral Region research biologist in Homer. “They’re also fairly aggressive and therefore easy to catch, and sometimes you can catch them in fairly shallow water, right next to shore.”

As the huge mouth filled with sharp teeth would suggest, lingcod are very predatory fish and will eat almost anything: herring, salmon, rockfish, crabs, shrimp, jellyfish, even other lingcod. The lingcod is not a true cod. Rather, it is the largest member of the “greenling” family, which includes Atka mackerel and the various greenlings. While greenlings can be found as far east as the Sea of Japan, the lingcod is unique to the west coast of North America, ranging from Sand Point on the Alaska Peninsula south to Mexico’s Baja Peninsula. In Alaska, they are common in open coastal areas from Kodiak east to the Copper River Delta, and in the fjords of Southeast Alaska.

Lingcod are long-lived, compared to many other fish, with some specimens aged to at least 26 years old. Most fish harvested in the Southcentral Alaska sport fishery are 8 to 16 years old. Lingcod prefer rocky areas, reefs and kelp beds, especially in areas of strong tidal movements. Male lingcod are widely known to guard nests of fertilized eggs for up to 11 weeks during the winter and spring season, but currently there is some debate on their movements.

It has been assumed that lingcod are fairly sedentary, staying within several hundred yards of a home site. However, recent studies may show that lingcod are more migratory than previously thought. One 1990 study reports significant numbers of fish moving nearshore and offshore in a bay in Washington. Recent tagging studies are beginning to show that lingcod may actually travel from two to more than 300 miles from their original tagging location. It may be that lingcod establish a “home” site, then frequently travel in search of food, and then return to their home site. Most studies show that the vast majority of the fish are recaptured within 4.5 miles of the tagging location.

In fact, their movements present one of their biggest research challenges. “Lingcod are actually fairly straightforward to study,” Meyer continues. “They don’t have swim bladders so they can be brought up from any depth without decompression injuries. They have a high rate of survival when released, so they can be successfully tagged.” However, because of their range of movement, and distribution over a wide area, it has been difficult to produce an estimate of the size of the population that would be useful to the Board of Fisheries.

Although lingcod continue to be an important recreational and commercial fish species in Southeast Alaska — primarily because of their large size, fine flavor, ease of catch, and because, in some areas, it is relatively easy to deliver fresh fish by jet aircraft — because the stock status is unknown, Alaskan fishery managers must be extremely careful.

“Lingcod are already fully allocated in Southeast Alaska,” continued Meyer, “and we haven’t yet used a stock assessment model to determine a harvest policy.”

The conservative approach is warranted. In 2000, the Pacific Fishery Management Council declared lingcod to be an overfished species in Washington, Oregon and California waters. The Pacific lingcod stocks have since been rebuilt. In Alaska, several areas have multiple special regulations to prevent overharvest, and research on lingcod movement and stock assessment continues.

In the meantime, however, you can help. Carefully release any lingcod that you don’t wish to keep, and keep lingcod only of legal size. Also, lingcod are often found very near yelloweye rockfish, a species of management concern, and one that has very strict regulations throughout the state. Lingcod are often found on the top of underwater pinnacles, while the yelloweye are usually on the deeper sides. To minimize yelloweye catch, avoid fishing the deeper water around pinnacles.

Lingcod flesh may seem a little blue, but changes to white after cooking. Try foil-wrapped in the oven with a little Parmesan cheese and zucchini, or coated with bread crumbs and sautéed in a little butter and fresh parsley.

Lisa Olson is an information officer with the division of Sport Fish, based in Anchorage.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.