Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

April 2007

What is Age Validation

and How Does it Relate to Fortune Cookies?

Years ago, while eating at a favorite Chinese restaurant in San Francisco, I had a fortune cookie state, “You will age well.” I didn’t realize then that this was a premonition. It foretold my future, but not exactly in the way I would’ve anticipated.

You see, when most people think of fishery biologists, they visualize people zooming around in boats in remote locations, catching, tagging and tracking fish. I’ve often been asked, “But what do you DO during the winter?” Winter months are busy with other duties – analyzing data, writing reports, planning for upcoming projects, and aging fish.

One of the myriad winter duties of a fishery biologist is to estimate the ages of fish species. This is done using various structures collected over the course of a field project. Structures commonly used for aging are scales, otoliths (ear “stones” or bones), fin rays, vertebrae, and opercula (gill covers). Knowing the ages of fishes allows fisheries managers to understand the dynamics of fish stocks and how fish populations react to environmental stresses like commercial and sport fishing, natural mortality and predation.

Each aging structure has its advantages and disadvantages, depending on the species of fish. Some structures such as otoliths and vertebrae require a dead fish and are often collected during creel and carcass surveys. Scales are one of the most commonly collected structures, are easily removed from most fish, and do not require the fish to be killed. However, the dimensions and growth of scales are directly correlated with that of the surface area of the fish. So, as the body approaches an asymptotic (maximum) and rate of growth slows down with the increase in size, scale size will do likewise. For some relatively short-lived fish such as the Pacific salmon species, by the time the fish reach their maximum size, they are ready to spawn and subsequently die. However, for relatively long-lived resident species such as inconnu (sheefish), lake trout and northern pike, scales have been shown to underage the fish, since once the fish stops growing, so does the scale. Some fish, like burbot, have minute, imbedded scales that lack discernable annuli (growth rings).

Next to scales, otoliths are the most popular structure to age. They are easy to collect and prepare for aging. Otoliths are small, paired white structures found in the heads of all fishes other than sharks, rays and lampreys. Otoliths provide a sense of balance to fish in much the same way that the inner ear provides balance in humans. Fish otoliths also aid in hearing.

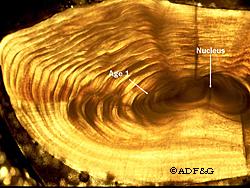

The basic idea on aging a structure is similar to what foresters do with trees: Count the growth rings, or in fishery terms, the “annuli.” However, acquiring ages from otoliths is not necessarily straightforward. The most difficult part of aging a fish using otoliths is trying to ascertain Year 1. From the photograph of a burbot otolith that has been cross-sectioned and viewed under a microscope with a polarizing filter, the first annulus is assumed to be the first distinct and complete dark zone formed outside the nucleus. Later years appear to be fairly straightforward with each annulus forming alternating light/dark rings. The light rings are usually larger and form during the summer months when food is readily available. During the winter, the rings will darken as growth slows. Unlike scales, otoliths will accrue material throughout the life of the fish even after the fish reach their maximum size.

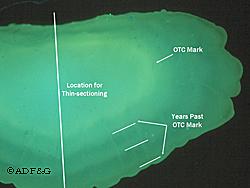

Because of the importance of acquiring accurate ages, many studies have been conducted for the purpose of proving that an aging structure and/or technique is valid. That is, what we think are annuli really are. One such study took place in 2000 with burbot. Back in 1995, 231 young burbot were injected with oxytetracycline (OTC), the same broad-spectrum antibiotic commonly prescribed by doctors to treat a myriad of bacterial infections in humans. The OTC antibiotic is commonly used as a marker because it binds with proteins in the blood and is incorporated in newly forming and mineralizing bone. The OTC is fluorescent under ultraviolet light and can accurately mark the date of application. Each of these OTC injected fish received a tag which identified them for later capture. The burbot were in two temporary settling ponds at the Fort Knox hard rock gold mining complex near Fairbanks. Between 1995 and 2000, 47 of the 231 OTC injected fish were captured and sacrificed for their otoliths.

The main purpose of the study was to estimate the proportion of correctly aged annuli past the OTC marks of burbot otoliths that were captured between 1996 and 2000. For each otolith pair, one was thin-sectioned and the other left whole. The thin-sectioned otoliths were sectioned through the center, epoxied to a microscope slide, and then ground until they were thin enough for light to easily transmit through. The otolith pair was then “read”; that is, a “reader” (me) estimated the ages past the OTC marks under a compound microscope that was also equipped with a mercury lamp that supplied the UV radiation. Care had to be taken, though, to minimize exposure of the otoliths to the UV as well as white light since the OTC mark will fade over time with exposure.

The burbot incorporated the OTC into its otoliths very well and the mark fluoresced bright as the northern lights in both the whole and thin-sectioned otoliths. I found the thin-sectioned otoliths to be easier to view under both the microscope with the mercury lamp turned on and with just the transmitted light with the polarizing filter in place. I was able to tell with the thin-sectioned and whole otolith pair what the annuli looked like, and knowing the time after injection with OTC, how many years should have elapsed past the fluorescing mark. Or, in other words, I was able to “age burbot otoliths well.”

Lisa Stuby is a research biologist who has worked for Sport Fish Division in Fairbanks since 1995. She has also supervised counting towers and supervised and/or assisted with radiotelemetry projects on salmon on the Copper, Unalakleet and Kuskokwim Rivers. Her office in Fairbanks is covered with salmon art.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.