Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

May 2007

White Mountain Elder Shares Caribou Stories

The Return of the Caribou to the Seward Peninsula

Jacob Ahwinona’s grandparents predicted that the caribou would return to the Seward Peninsula.

“Someday they’ll come back. When we’re gone, in your time they will come back,” he remembers them telling him. He is grateful that he has been able to see their prediction come true.

“I got to see the day,” he said. “They knew what they were talking about.”

Ahwinona was ‘Guest Elder’ at the February 2006 meeting of the Western Arctic Caribou Herd Working Group in Anchorage. He was born in Death Valley, northeast of White Mountain, a small community about 50 miles east of Nome.

During much of the 1800s the Western Arctic Caribou Herd wintered on the Seward Peninsula in northwestern Alaska. But in the late 1800s, for reasons not entirely understood, the caribou shifted their winter range to the Nulato Hills east of the Seward Peninsula. The loss of this subsistence resource caused local Natives to place more dependence on marine mammals, which were being depleted by commercial hunting.

About this same time reindeer and reindeer herding were introduced to the Seward Peninsula as a way of providing a more reliable food source for the Native population. Caribou and reindeer are the same species, but reindeer have been domesticated and kept by herders in Europe and Russia for centuries. Reindeer were first brought to western Alaska from neighboring Russia in1892. Chukchi reindeer herders, and later Sami herders from Norway, were employed to teach Alaskan Inupiat and Yup’ik Natives reindeer husbandry. Reindeer herding thrived for nearly 100 years on the Seward Peninsula, and 15 Native-owned herds were under active management through the late 1900s.

In 2000, the Western Arctic Caribou Herd unexpectedly began to range farther and farther west onto the Seward Peninsula during the fall and winter months. When the herd of over 400,000 caribou made their annual trek north to their spring calving grounds on the North Slope, they swept whole herds of domestic reindeer along with them, wiping out many second and third generation Native reindeer herders.

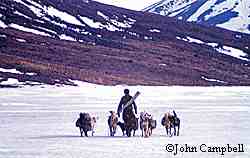

Although wild caribou were absent from the Seward Peninsula during his lifetime, Ahwinona had the opportunity as a young man to hunt caribou in the Nulato Hills to the east. He and his group hunted caribou by dog team, with the guidance of an elder.

“There were no snowmachines,” he said. “I had a good dog team – a basket sled and 11 dogs.” He recalled camping in the snow, stalking caribou by snowshoe and learning to “shoot downhill.” The elder, a guide for the group, told them where to hunt, which caribou to shoot, and when to shoot it.

Ahwinona and his hunting group came upon 13 caribou near the headwaters of the Shaktoolik River and caught 11 of them under the “strict” guidance of the elder. “Two got away,” said Ahwinona, who indicated it was his first and last caribou hunt. “After that hunt, I went to work.”

Despite that, he clearly remembers the stories his parents and grandparents told of earlier times when they would follow the caribou from their wintering grounds on the Seward Peninsula all the way to their calving area near Point Hope. “They walked with packs on their dogs. My grandparents had 13 dogs. And my grandparents said they would see gold in the creeks along the way,”

Ahwinona also learned from his grandparents how they hunted caribou from kayaks before they had guns. Jacob’s grandfather, Tookoona, was a fast runner, and when the caribou would arrive at Salmon Lake on the Seward Peninsula, he would drive them over a low pass and into Safety Lagoon. “Hunters in kayaks on the beach would be waiting with spears and knives. When the caribou started swimming out they would kayak out and spear them,” Jacob told the group. Others would butcher the animals on shore. Ahwinona stressed how in the days before they had guns, a successful hunt required the cooperation of the entire village.

Ahwinona’s parents and grandparents also taught him to utilize everything from the caribou. “We were brought up to respect the land and subsistence living, and our natural resources,” he emphasized. “You don’t kill unless you are going to eat the animal.” He said it was a time when, “we listened to our elders, and you didn’t waste caribou. When I go out and see animals wasted it hurts me in here,” he said as he pointed to his heart. “It hurts you, and it also hurts the future of the caribou.”

Sue Steinacher is wildlife information specialist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game in Nome, and also edits Caribou Trails, the newsletter of the Western Arctic Caribou Herd Working Group

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.