Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

April 2008

Rockfish Through The Ages

Local Traditional Knowledge of Rockfish

Rockfish have been harvested by Alaska Natives in Southeast and Southcentral Alaska since the earliest-known human occupation of the areas. Remains of rockfish have been found in a 9,000-year-old archaeological site in the Prince of Wales Archipelago. Rockfish bones have been found in two archaeological sites in Mitchell Bay, near the village of Angoon. Remains of bottomfish have also been found in archaeological sites in Prince William Sound.

Over 30 species of rockfish (Sebastes) inhabit the waters of the Gulf of Alaska. As a species, rockfish are sedentary, long-lived, slow to reproduce, and reproduce in low numbers. As such, the population cannot sustain high levels of mortality from fisheries, and may suffer from local depletion. The Alaska Board of Fisheries has recognized subsistence uses of rockfish in Southeast Alaska, Prince William Sound, Cook Inlet, and Kodiak, among other areas.

Documentation of local traditional knowledge (LTK) of rockfish is the primary objective of a joint project of the ADF&G Division of Subsistence and the North Pacific Research Board. The project entails interviews with key respondents in Sitka in Southeast Alaska, and Nanwalek, Port Graham, and Chenega Bay in Southcentral Alaska.

The Tlingit of Southeast Alaska have indigenous names for at least two species of rockfish: léik’w for yelloweye rockfish (Sebastes ruberrimus), locally known as red snapper, and lit.isdúk for black rockfish (Sebastes melanops), locally known as black bass. In the Alutiiq language, the general term for rockfish is tu kuq, which can also refer specifically to black bass, while yelloweye rockfish are ushmaq.

Traditionally, rockfish were eaten fresh although not consumed in the quantities that salmon or halibut were. However, the amount of rockfish consumed does not reflect the importance of rockfish in the Native diet. In Southeast Alaska, rockfish were harvested during the winter and early spring, when it was difficult to obtain fresh fish. Winter rockfish fishing was conducted in sheltered areas near shore; in the spring, rockfish as well as halibut were taken in more open waters. Young men or boys, accompanied by an uncle, went fishing for rockfish during the winter months. The uncle supervised the fishing to make sure that the appropriate amount of fish was caught.

In Prince William Sound, bottomfish, including rockfish, were harvested throughout the year, as weather permitted. In Lower Cook Inlet, these fish were taken primarily during the summer. Rockfish were also mostly eaten fresh in these areas, but after the introduction of salt by Europeans rockfish were occasionally preserved by salting.

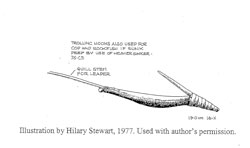

Prior to European contact, wood and bone were used for fishing hooks, and fishing line was made from kelp, cedar bark, twisted spruce root, or rawhide. In Southeast Alaska, several types of traditional hooks were used for catching rockfish: circle and U-shaped hooks were “jigged” on a hand line, and a simple compound V-shaped hook, constructed of a barb of sharpened bone or wood attached to a wooden shank, was set in deep water by use of a heavy sinker. A Tlingit elder interviewed in Sitka said that, prior to European contact, people used hooks made from, “That heavy abalone shell from California . . . It flashes when you’re yanking it back and forth.” These indigenous hooks were eventually replaced by copper and lead hooks, scraped and polished to make them shiny.

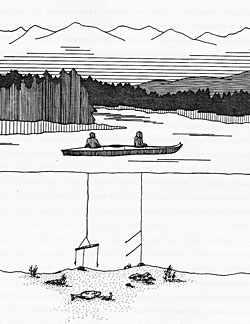

Longlines with multiple hooks, referred to as “skates” in Alaska, were also used by Tlingits to target bottomfish. Heavy stones were fastened to both ends of a main line, and multiple hooks were spaced about six feet apart. An inflated seal bladder was attached to one end of the main line to act as a buoy. The hooks were baited with clams or bits of fish and the gear was set on sand or mud banks and left to soak for one tide change.

In Southcentral Alaska, rockfish, along with other bottomfish, were harvested with modified hand lines. In Port Graham and Nanwalek, the lines were called nuakatat and made from smoke-dried kelp roots rolled tightly together, or of sinew. The line was attached to a horizontal bar from which several hooks and weights were suspended. In the first decades of the 20th century, residents of Nanwalek and Port Graham used single-hook hand lines made from seine net hanging twine. Another method used was rrtuwaq, which means “to swing it and throw out.” Anglers fishing from the beaches caught several species of fish using this method. The line was thrown out, tied to a log, heavy rock, or other anchor, and left overnight or through a tidal cycle. The hooks were usually baited with fish heads or tails.

Rod and reel has largely replaced hand lines as the primary gear for harvesting rockfish today. Bait or commercially-made lures are used. Respondents fishing for halibut say their incidental harvest of rockfish is low because their longlines are not set in deep waters or over rocks, and the lines are most often pulled by hand.

Key respondent interviews and survey results reveal that Sitka fishers catch rockfish with both longline and rod and reel. Key respondents stated that they target halibut with longline gear, while the preferred gear for rockfish is rod and reel. Respondents set their longline gear on sandy or muddy bottoms, away from rocks, pinnacles and coral structures, to avoid both snagging their gear and catching rockfish. Several respondents said that the type of bait used on longline gear also deters rockfish. One respondent said that rockfish prefer herring or other fish and octopus. Another respondent said that he uses larger hooks and bigger pieces of bait to avoid catching rockfish, and another has found that hooks spaced at least 5 to 10 feet apart on a longline tend to catch fewer rockfish.

Our research has found that rockfish have been harvested in Alaska for centuries and continue to be taken for subsistence purposes in many coastal Alaska communities.

ADF&G Division of Subsistence staff members Mike Turek, Bill Simeone, Davin Holen, Nancy Ratner and Lisa Olson contributed to this article.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.