Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

April 2025

Stalking Shorebirds on Alaska’s Remote Outer Coast

Part 4 The final season: 2024

The pilot season was featured in January and the first two seasons in February and March. Jenell Larsen Tempel picks up the story as the project progresses and wraps it up this month.

This time last spring I was beginning my field preparations for our final 2024 season. Technicians were already hired, safety training dates were set, and flight schedules were ironed out. It was a different type of field season for me. I had a knee injury that resulted in an ACL and meniscus repair and this year I would be managing the project from afar rather than from afield, as my knee was not recovered enough for hiking.

My plan was to be based in Cordova, about 70 miles west of the study area, for five weeks. I would serve as the daily safety point of contact, do all the resupply shopping, submit technician timesheets, enter data, ship biological samples, and shuttle technicians and biologists to the airport and bunkhouse when crew switches occurred. In my first season I did not hire someone to do these things. Rather, I relied on Charlotte Westing, the area biologist in Cordova and her administrative assistant Samantha Renner to handle Cordova responsibilities, and my husband in Douglas was my daily check-in person and weather forecaster. Administrative staff in the Juneau office handled all the crazy timesheets that we sent to them via Inreach messages. It worked, but I felt that I was burdening people with extra duties and that it could have gone smoother if I had just one person to do all the logistics from town. So, in 2023, I hired someone whose job was to run all the logistics. This worked out splendidly. Now this would be my role.

I had a blend of returning staff and newcomers in 2024. Tory Rhoads, a Juneau-based wildlife biologist in my program, stepped into my earlier role running the ADF&G field camp. Tory has a plethora of field experience including fisheries work and a decade of bat research projects. I  trusted her judgment in the field and knew she had all the skills to run a field camp and oversee the crew of three people. Aside from Blake, my returning photographer, the others stepping into the field were new faces.

trusted her judgment in the field and knew she had all the skills to run a field camp and oversee the crew of three people. Aside from Blake, my returning photographer, the others stepping into the field were new faces.

The Forest Service (FS) crew was all returning staff, which I was extremely grateful for. Even though it was our third year, I still had some difficult decisions to make about camp placements. In the past the FS crew ran the Bering River camp and ADF&G ran the Okalee Spit camp. This worked well but the Bering River camp was a mile bushwack from the coast before you were at the closest of the two survey polygons (study areas) and a five-mile bushwack before you even made it to the far polygon. For the crew doing the far polygon this  resulted in a daily roundtrip commute of 12 to 14 miles depending on how much walking you did to get to the birds that day. It was not energy efficient, but it was a good campsite, and good sites were hard to find. It was in a wooded area, well protected from high winds and had a good freshwater source. The trouble with moving it closer to the birds was finding a landing zone that would not get too wet for the fully loaded beaver aircraft to land. The amount of moisture on the coast fluctuates greatly from year to year depending on snow conditions and air temperature, which effect the breakup dates of frozen rivers and snowmelt. While 2023 was a wetter year, 2024 was drier. This was welcome news. I did a recon flight with our pilot Steve to check out the potential of moving the Bering Camp closer to the Red Knot hot

resulted in a daily roundtrip commute of 12 to 14 miles depending on how much walking you did to get to the birds that day. It was not energy efficient, but it was a good campsite, and good sites were hard to find. It was in a wooded area, well protected from high winds and had a good freshwater source. The trouble with moving it closer to the birds was finding a landing zone that would not get too wet for the fully loaded beaver aircraft to land. The amount of moisture on the coast fluctuates greatly from year to year depending on snow conditions and air temperature, which effect the breakup dates of frozen rivers and snowmelt. While 2023 was a wetter year, 2024 was drier. This was welcome news. I did a recon flight with our pilot Steve to check out the potential of moving the Bering Camp closer to the Red Knot hot  spots. If the birds behaved like in years past, moving the camp to the mouth of the Campbell River would essentially put the crew right on top of them and even out the distances walked to reach each polygon. (Campbell River camp, right). I also knew from experience that the drinking water up the Campbell River was the best in this stretch of the bay. The drawbacks were that this area didn’t have much wind protection (there were very few trees to serve as a windbreak) and that conditions could change. The dry, sandy dunes surrounding the Campbell could become saturated with heavy rainfall, or flood water due to warm temperatures increasing meltwater. It was a gamble, but I decided to take it and make some adjustments. My ADF&G crew would run this camp so that if the beaver could not land here, using the helicopter

spots. If the birds behaved like in years past, moving the camp to the mouth of the Campbell River would essentially put the crew right on top of them and even out the distances walked to reach each polygon. (Campbell River camp, right). I also knew from experience that the drinking water up the Campbell River was the best in this stretch of the bay. The drawbacks were that this area didn’t have much wind protection (there were very few trees to serve as a windbreak) and that conditions could change. The dry, sandy dunes surrounding the Campbell could become saturated with heavy rainfall, or flood water due to warm temperatures increasing meltwater. It was a gamble, but I decided to take it and make some adjustments. My ADF&G crew would run this camp so that if the beaver could not land here, using the helicopter  was an option for camp breakdown and crew switches. This was not an option with FS due to their own aviation rules.

was an option for camp breakdown and crew switches. This was not an option with FS due to their own aviation rules.

After multiple shuttles, I dropped everyone and all the gear off at the airport on May 5th. It was a bittersweet feeling riding back in the truck alone. I was sad that I was not partaking in the shorebird spring, thinking I may never put my feet in the mud again on that spectacular slice of the Lost Coast. But soon I was too busy to be melancholy. I was the one sending out weather updates, was on call from sunup to sundown as I got safety check-ins, data reports on specific flag IDs and numbers of flags recorded, and kept a running list of needed items from the store for the weekly resupply. One of the activities I enjoyed the most was tracking the migration, as this wasn’t something I could do in the field. I corresponded with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and their Red Knot field crew to get updates on numbers of birds sighted and how many leg flags they were getting. The Washington crew was utilizing the same methods I was to develop their own abundance estimate. Ebird was another asset in tracking migration. I regularly checked reports from local birders down in Washington to see the flock sizes that were present in Willapa Bay and Greys Harbor. When flock sizes were large, I knew the migration was peaking down there and it would be about a week until our numbers jumped up.

Tracking migration with Motus

Another useful tool we had were Motus towers. "Motus" is a Latin word meaning "movement" or "motion," and is  the name of the Motus Wildlife Tracking System, an international collaborative research network that uses radio telemetry to track the movements of migratory animals. The tower is essentially a sturdy pole about 12-meters high with several antennas. Motus towers act as receiving stations that use automated radio telemetry to pick up signals from birds with Motus tags. The Motus tags are very small. In fact, the tags are so small they can even be attached to flying insects like dragonflies! Above: A biologger and a Motus tag on the back of a Red Knot tagged in Mexico. The very thin antenna can be seen extending behind the bird. The tags send out radio signals, which are individually unique and digitally encoded. Stationary Motus towers use a shared frequency, so

the name of the Motus Wildlife Tracking System, an international collaborative research network that uses radio telemetry to track the movements of migratory animals. The tower is essentially a sturdy pole about 12-meters high with several antennas. Motus towers act as receiving stations that use automated radio telemetry to pick up signals from birds with Motus tags. The Motus tags are very small. In fact, the tags are so small they can even be attached to flying insects like dragonflies! Above: A biologger and a Motus tag on the back of a Red Knot tagged in Mexico. The very thin antenna can be seen extending behind the bird. The tags send out radio signals, which are individually unique and digitally encoded. Stationary Motus towers use a shared frequency, so  they operate as a network, rather than a solo tool used by one researcher. Once a tagged bird is detected by a tower a “tag report” is generated and the data is stored in a computer that is connected to the tower. Originally (and still in some cases) researchers manually download data that is received and stored by the Motus tower through a microSD card, but with new technology there is a convenient upload option through a cellular network which is what is being used on the Copper River Delta and the Controller Bay towers. Pictured here - setting up a Motus tower, and below, left, a tower on Egg Island on the Copper River Delta. In this instance the data are transcribed and relayed to the Motus website rather quickly. Although we did not have cell service at camps or throughout the bay, if one hiked out to the end of the spit, a bar or two of cell service could be found and this is what the Motus tower at our site relied on. FYI this was good enough to send a text but not very good for calls, downloading music, or audio books! Lastly, the towers work in very remote locations without cell service or internet. In this case the data must be downloaded

they operate as a network, rather than a solo tool used by one researcher. Once a tagged bird is detected by a tower a “tag report” is generated and the data is stored in a computer that is connected to the tower. Originally (and still in some cases) researchers manually download data that is received and stored by the Motus tower through a microSD card, but with new technology there is a convenient upload option through a cellular network which is what is being used on the Copper River Delta and the Controller Bay towers. Pictured here - setting up a Motus tower, and below, left, a tower on Egg Island on the Copper River Delta. In this instance the data are transcribed and relayed to the Motus website rather quickly. Although we did not have cell service at camps or throughout the bay, if one hiked out to the end of the spit, a bar or two of cell service could be found and this is what the Motus tower at our site relied on. FYI this was good enough to send a text but not very good for calls, downloading music, or audio books! Lastly, the towers work in very remote locations without cell service or internet. In this case the data must be downloaded  manually, periodically or at the end of the season, on a microSD card which is then uploaded to the Motus website by the user.

manually, periodically or at the end of the season, on a microSD card which is then uploaded to the Motus website by the user.

Best of all, Motus allows for public access to available data for any tower that is registered. By visiting motus.org anyone can click on any active Motus station on the interactive map and see what species are being tagged and tracked and even look at individual migration routes by clicking on the animal ID. It’s not a perfect system, but it has been very useful for tracking migration and specific stopover locations, especially for migratory birds. Detections of tagged animals depend on the distance to the tower (our tower in Controller Bay can detect tags from as far as 15 km away), type of tag that is being used, the terrain (if there are mountains, hills or trees), and the direction in which the tower’s antennae are mounted. While some Motus stations have omni-directional antennae, we used four, directional antennas pointed at different parts of the key staging areas of the bay to help maximize range and detections. Additionally, the Motus coverage in Alaska is not widespread like it is in much of the Lower 48. The very first Motus tower in the state was launched in 2021 at Alaganik Slough, a location on the Copper River Delta. In 2022, an additional tower was put up  to monitor shorebird passage on Little Egg Island, also located within the Copper River Delta. In 2023, when we launched the Controller Bay motus tower, there were 1,200 motus stations across 31 countries and there were five in Alaska, three of them being within the Copper River Delta and Controller Bay area. Because there were no stations north of Beluga, Alaska, (across Cook Inlet from Anchorage) no detections would occur on the breeding grounds. We can’t use Motus to track birds where there are no nearby towers. All of this is to say that the ability of the towers to detect tagged critters is not perfect, but it allows for remote sensing in one spot for 24/7, and it even has the ability to pick up flybys or birds at night. Currently the website shows seven towers in Alaska that reported last season and the network is continuing to expand with biologists and research groups in the Pacific Flyway.

to monitor shorebird passage on Little Egg Island, also located within the Copper River Delta. In 2023, when we launched the Controller Bay motus tower, there were 1,200 motus stations across 31 countries and there were five in Alaska, three of them being within the Copper River Delta and Controller Bay area. Because there were no stations north of Beluga, Alaska, (across Cook Inlet from Anchorage) no detections would occur on the breeding grounds. We can’t use Motus to track birds where there are no nearby towers. All of this is to say that the ability of the towers to detect tagged critters is not perfect, but it allows for remote sensing in one spot for 24/7, and it even has the ability to pick up flybys or birds at night. Currently the website shows seven towers in Alaska that reported last season and the network is continuing to expand with biologists and research groups in the Pacific Flyway.

The Motus tracking of Pacific Red Knots is a flyway-wide effort being led by our partner Julian Garcia Walther down in Mexico as part of his PhD project. Julian conducted the captures of these birds on the wintering grounds in northwestern Mexico in the spring. The tags don’t usually stay on for a full year, so the best we can hope for is that the tags stay on for half the migratory journey and maybe if we are lucky on a few, the full journey from Mexico to the Arctic and back. In 2023 and 2024 we were lucky enough to have a Motus tower on the tip of Okalee Spit plus the two other locations along the Delta.

Motus tracking lets us visualize the whole migration from Mexico to Alaska, and allows us to understand migration ecology on a large scale. For instance, you can intimately see the migration of a single bird and look at the route it took and determine if it got off course or used any unexpected stopover locations or habitats. Julian’s project is focused on understanding large scale migration patterns like these. But Motus is also useful for understanding habitat use on a small scale. For my work, I was most interested in the habitat use of knots in the Copper River Delta Complex and Controller Bay. The towers could tell us how long the birds were stopping over, if the birds were visiting all three sites where the towers were, if they had a preferred site, or if their visits were correlated with tide, time of day, or weather events. And perhaps best of all, it let me jest my crew a bit. “You guys, six Motus-tagged birds were detected from the Controller Tower yesterday!” I could message them or relay on the satellite phone. “Have you seen any of the Motus tags?” We rarely saw the tags. Although there is a fine antenna that sticks out several inches beyond the bird’s tail, it was just too difficult to make out.

Managing the field from afar

As the town of Cordova became more and more lively with fishermen and women, the bunkhouse filled up with ADF&G fisheries technicians. When space became limited, I moved out to an apartment that one of my FS  collaborators owned for the following three plus weeks. Heavy downpours ensued out my window for three straight days in town and I thought of my crew. The weather reports I was sending them were not good, but likely, their weather was better out on the open coast where clouds are pushed on by gusts of wind and intermittent sunshine could be found. I’ve learned from experience that weather passes more quickly on the outer coast. Our first resupply was scheduled for May 11th and Tasha DiMarzio was going out to replace Charlotte. Tasha has long red hair and a combination of tan skin and freckles from endless hours spent in the field chasing, counting, and tagging waterfowl. She works for the Waterfowl Program at ADF&G and came recommended to me by several people in the department as an amazing bird biologist and outdoors athlete when I began the project in 2022. She came out

collaborators owned for the following three plus weeks. Heavy downpours ensued out my window for three straight days in town and I thought of my crew. The weather reports I was sending them were not good, but likely, their weather was better out on the open coast where clouds are pushed on by gusts of wind and intermittent sunshine could be found. I’ve learned from experience that weather passes more quickly on the outer coast. Our first resupply was scheduled for May 11th and Tasha DiMarzio was going out to replace Charlotte. Tasha has long red hair and a combination of tan skin and freckles from endless hours spent in the field chasing, counting, and tagging waterfowl. She works for the Waterfowl Program at ADF&G and came recommended to me by several people in the department as an amazing bird biologist and outdoors athlete when I began the project in 2022. She came out  for a stint during the inaugural year and took to the work, “like a pig to mud,” as my pilot said, who knew Tasha from years of flying with her on goose work in the Delta.

for a stint during the inaugural year and took to the work, “like a pig to mud,” as my pilot said, who knew Tasha from years of flying with her on goose work in the Delta.

I picked Tasha up from the airport on Friday afternoon. “The weather is looking pretty crappy for tomorrow,” I told her once we were in the pickup. “We will be on standby in the morning, but Steve thinks we will need to cancel. Sorry but you might be stuck in town an extra day.”

“That’s alright, we can go birding out at Hartney Bay and the Delta,” she said cheerfully. “Now how many flags did you guys end up getting last year? What’s the number I need to beat?” (Flagged Red Knot, above right)

I loved her competitive edge. “We had 46,” I smiled. “You’ll be out at Okalee Camp with the Forest Service crew this year, plus one new Fish and Game technician named Nate. He’s great and I hired him on as a photographer, but he might need some guidance out there.”

“Oh, has he worked with you before?”

“No, not at all. I actually met him packrafting up in Haines over the summer and he was really interested in what I was doing and wanted to come work on my Red Knot project. He’s very competent outdoors, has a background in guiding, and I think it’s going ok out there, but I don’t hear much from him on the Inreach. The Forest Service crew also has a new International Programs Biologist named Sharon, and I want to make sure she’s doing ok out there too.”

“No, not at all. I actually met him packrafting up in Haines over the summer and he was really interested in what I was doing and wanted to come work on my Red Knot project. He’s very competent outdoors, has a background in guiding, and I think it’s going ok out there, but I don’t hear much from him on the Inreach. The Forest Service crew also has a new International Programs Biologist named Sharon, and I want to make sure she’s doing ok out there too.”

Tory and I know each other well and she communicated the happenings at the Campbell Camp with me at all hours of the day. I could always count on her for Red Knot numbers, coyote sightings, or funny snippets. But the male dominant crew at Okalee Spit was not as vocal. I mostly got responses like, “I’m doing fine” or “it’s all good.” Tasha knew not being out there was killing me inside and I knew I could count on her to give me honest feedback on how everyone was doing out there, if the crew was getting the data, and to tell me if anything was needed to boost morale. The best way to boost morale at a field camp is usually through food. So, Tasha made  sure that her resupply trip included tasty snacks from Anchorage that could be hard to come by in Cordova during the height of fishing season -- like goat cheese, cheese curds, hummus, fresh salad and vegetables, power bars that were flavored like donuts and cake, and some specialty food items for folks in camp that were vegetarian or diary intolerant. We baked brownies that night to send out to both camps and at the request of my Bering Crew I purchased large quantities of Oreos.

sure that her resupply trip included tasty snacks from Anchorage that could be hard to come by in Cordova during the height of fishing season -- like goat cheese, cheese curds, hummus, fresh salad and vegetables, power bars that were flavored like donuts and cake, and some specialty food items for folks in camp that were vegetarian or diary intolerant. We baked brownies that night to send out to both camps and at the request of my Bering Crew I purchased large quantities of Oreos.

As soon as she was on the ground at Okalee Spit the communication picked up.

“Nate’s doing awesome, he fits right in.” “I don’t think Sharon has been in the field this long before and could use a break in town at the next resupply.” “Four leg flags total today, numbers are picking up.”

She and Nate paired up and while she counted and glassed for flags, Nate squatted alongside her photographing  them. (Nate, above, photographing Red Knots; right, back at camp after getting the shots. Below, the tagged Red Knot in flight.)

them. (Nate, above, photographing Red Knots; right, back at camp after getting the shots. Below, the tagged Red Knot in flight.)

“At one point I think he held a squat for 45 minutes as we waited for the tide to push the birds towards us,” she told me. “He was completely exhausted. I think I pushed him pretty hard.”

But he did get an awesome shot of a Motus tagged bird in flight! On May 17th the Okalee Camp reported 15 leg flags in a single day, setting a new all-time high! By the end of the week when Tasha departed, we had racked up 41 individually flagged birds and still had one more week of fieldwork. We were on track to blow our previous season’s count out of the water.

Stopover abundance

I didn’t have a final count of flags when we pulled camp. Not all the flags were reported to me (some were simply on datasheets but not relayed to me in daily comms), and I think some of my FS friends liked making me wait desperately for numbers and withheld information deliberately. There were multiple days where we had duplicate reports, and we needed some time to sort through the photos to ensure we didn’t miss any birds. I spent much of June going through datasheets of resighted birds and sorting through photos saved to numerous folders, and submitting information to the Bird Banding Lab for confirmation. At the end of the season my gut feeling was that we had ~75 or 80. As it turns out, all in all, we had a total of 97 individually marked birds and 29 of them were resighted across more than one day! This was astonishing. All but a few had photographic evidence. From corresponding with the crew in Washington state (the ones using the same methods to estimate the stopover abundance at Greys Harbor and Willapa Bay) they recorded 96 individually flagged birds at the end of their season and they also found it to be an excellent resight season. What was particularly mind-blowing about this was that it has been assumed that almost all of the population stops in these coastal Washington sites. That fact that we had nearly the same number of resights made me wonder if most of the population also stopped in Controller Bay in 2024. This really demonstrates how important Controller Bay is for this population.

Months later, working with biometrician Grey Pendleton, we estimated that the stopover population size in Controller Bay in the spring of 2024 was about 16,590 Red Knots. Using the former population estimate of 21,770 knots this would indicate that about 76% of the population stopped over in Controller Bay. Our 2023 results indicated that about 9,000 knots used the bay that year and resulted in 42% of the population stopping over. All of these results are preliminary at this time. In the coming months I’ll be hunkering down to  finish the data analysis and start preparing a scientific paper for publication, but as of right now these are the numbers we have.

finish the data analysis and start preparing a scientific paper for publication, but as of right now these are the numbers we have.

One question that comes to mind is, why the variance from 2023 to 2024? Was it truly from an increase in birds? Or did we increase our skill in detecting them? Why would so many more birds stop in 2024 compared to 2023? Could this be driven by environmental conditions? We don’t have all the answers to these questions, but I hypothesize that it was truly an increase in the number of birds. Our effort didn’t change from 2023 to 2024, we covered the same polygons, i.e., surveyed the same area daily across both years. While having returning members helped folks to be familiar with the survey protocol, I do not think the field crew alone could make up the difference. Biologists in Washington also reported that it was an excellent resight year and they had been doing this method and fieldwork for several years prior. One explanation could be that more flags were put out prior to the 2024 season. Julian put out 42 new leg flags during the fall of 2023 and spring of 2024. In the previous season he was able to put out only 23. Still, this is not a tremendous amount given the population is estimated at nearly 22,000 birds.

Washington also reported that it was an excellent resight year and they had been doing this method and fieldwork for several years prior. One explanation could be that more flags were put out prior to the 2024 season. Julian put out 42 new leg flags during the fall of 2023 and spring of 2024. In the previous season he was able to put out only 23. Still, this is not a tremendous amount given the population is estimated at nearly 22,000 birds.

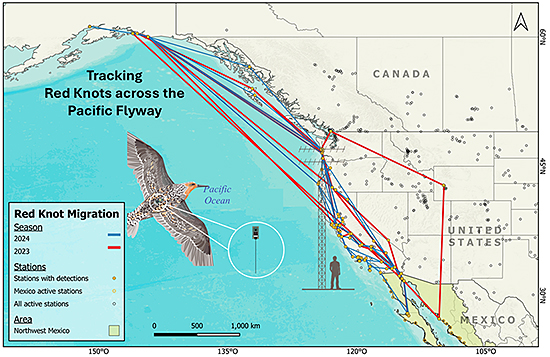

Migratory connectivity

The results from two years of tracking data following birds on their spring migration showed us some interesting patterns. It has always been assumed that Red Knots are tied to the coast, except for the short time they spend during the breeding and nesting season in the Arctic. What we expected to see was that the knots would follow a coastal route as an energy-minimizing strategy. From 25 tagged knots in northwestern Mexico, individuals actually tended to follow three general routes: a coastal route, a desert route and an inland route. You can see one  individual took a detour very far inland and was picked up in Wyoming! Julian originally hypothesized that a storm that coincided with this bird’s migration was responsible for throwing it off course. However, he noticed that other tagged birds departed at the same time, also experiencing this storm, but didn’t seem to wind up beyond inland California. Likely, he surmised, this was a juvenile bird experiencing its very first migration and got a bit lost! Somehow it knew to fly west and was reunited with other knots in coastal Washington.

individual took a detour very far inland and was picked up in Wyoming! Julian originally hypothesized that a storm that coincided with this bird’s migration was responsible for throwing it off course. However, he noticed that other tagged birds departed at the same time, also experiencing this storm, but didn’t seem to wind up beyond inland California. Likely, he surmised, this was a juvenile bird experiencing its very first migration and got a bit lost! Somehow it knew to fly west and was reunited with other knots in coastal Washington.

I dove into the finer scale habitat use of Red Knots across the Copper River Delta from the birds that the towers picked up in 2023. In that year we had five birds detected across Controller Bay and the Copper River Delta. All five were tagged on the same day in the Gulfo de Santa Clara in Mexico in April 2023. What I found was that almost all of the birds used all three sites, they did not backtrack to more southern foraging sites, and they tended to stop the longest at Controller Bay. Red Knot 859 tagged in Mexico, and photographed a year later in Controller Bay, Alaska. It is in non-breeding plumage in early spring and breeding plumage in Alaska. However, time spent across the Delta (including Controller Bay) as a whole, ranged from one to six days with an average of three days. This is very short! I expected that birds might forage for three or four days in Controller Bay alone, as were the results from a previous telemetry study, and then would stop for only a day or two at Alaganik and Little Egg Island on the delta.

Red Knot 859 tagged in Mexico, and photographed a year later in Controller Bay, Alaska. It is in non-breeding plumage in early spring and breeding plumage in Alaska. However, time spent across the Delta (including Controller Bay) as a whole, ranged from one to six days with an average of three days. This is very short! I expected that birds might forage for three or four days in Controller Bay alone, as were the results from a previous telemetry study, and then would stop for only a day or two at Alaganik and Little Egg Island on the delta.

For a bird that can fly for hundreds or thousands of miles without stopping, likely the entire Copper River Delta River Complex (including Controller Bay) is seen as just one town on their way north, with each bay, river mouth or barrier island appearing as a single restaurant. From a conservation perspective, this indicates that all of these locations are of great importance to this species, as well as the other five million shorebirds that are stopping to forage in each of these locations. But I still think Controller Bay is especially important for knots. Given that our tagged birds stay there longer, it is likely the first pit stop they see from the air that promises rich feeding grounds. Much of British Columbia and Southeast Alaska is comprised of rocky intertidal, making it difficult for knots to probe their bills into the sediment and effectively forage on clams. We know there are several other large river deltas containing sand/mud sediment that could also provide food for them like the Stikine, Alsek and Dangerous Rivers, but there is a lack of information on shorebird use at these locations, particularly the latter two as they are uninhabited and few birders, or people in general find themselves there in April or May.

There are still mysteries to solve related to Red Knots. And I’m hoping to contribute to solving several of them. The lab work for our diet questions will continue for the next year or two. Although we have some answers on numbers of knots using Controller Bay, efforts are underway to develop estimates for Coastal Washington and the overwintering grounds in northwest Mexico - both locations have ongoing resighting fieldwork. This will give us information we can use to infer an updated population estimate and help us understand if the population is stable, declining or even increasing.

This spring I’ll head back to Cordova to finish up the project and ship back the bikes, tents, cook stove, and cooler to our Fish and Game storage unit in Juneau. I’ll do some final benthic sampling to boost our sample size of Limecola balthica clams. But what I’m looking forward to the most is connecting with all the friends I have made while working on this project. I’ll be presenting my work to the community at the annual Copper River Delta  Shorebird Festival in May. It will be a mixed audience of serious and casual birders, local families, and visiting biologists. I’m excited. I’ve never been able to take part in the festival before because it always coincided with our field launch. I used to work on marine mammals and fish. And while I loved that work too, the research I have been doing with shorebirds has made me feel connected to others in ways those other projects did not. I have spent time in the field with birders, artists, college students, waterfowl hunters, guides, large game biologists, and international biologists. I have connected with researchers from Peru, Chile, Mexico, the Netherlands, Washington, New England, and all across Alaska.

Shorebird Festival in May. It will be a mixed audience of serious and casual birders, local families, and visiting biologists. I’m excited. I’ve never been able to take part in the festival before because it always coincided with our field launch. I used to work on marine mammals and fish. And while I loved that work too, the research I have been doing with shorebirds has made me feel connected to others in ways those other projects did not. I have spent time in the field with birders, artists, college students, waterfowl hunters, guides, large game biologists, and international biologists. I have connected with researchers from Peru, Chile, Mexico, the Netherlands, Washington, New England, and all across Alaska.

On particularly nasty days in Southeast Alaska when the Taku winds blow and sideways rain pelts me in the face, I think of Controller Bay. I’ll think of those knots on the mud flat, their feathers blown upwards in the wind and rain drops the size of their toes hitting them on the head. I like to think of where they are during other times of the year. Sitting at a salt lake in a desert in California or running with their toes in the sand on the coast of Mexico fat and happy, bolstered by fresh clams and the surf. I think of all the humans that get to see these mighty little athletes as they trapse across the globe.

My husband knows my affinity for this work runs deep. One day we will take our own fat tire bikes (we bought ours after the initial reconnaissance trip we took there four years ago) there he assures me. “When you forget how it felt in the field and you miss it, we can pack up our binoculars and do our own great migration on the Lost Coast.”

Stalking Shorebirds on Alaska’s Remote Outer Coast - Researching Elusive Red Knots

More on the Threatened, Endangered and Diversity Program at ADF&G

Photos ADF&G by Jenell Larsen Tempel, Blake Richard, Nate Arrants, Danny Casner, Tasha DiMarzio, and Lyda Rees. Photos of Red Knots in Mexico by Julian Garcia Walther, photo of Motus tower on Little Egg Island by Erin Cooper, USFS.

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) reviews programs and projects to ensure animal welfare. IACUC protocol numbers for work done for 2024: 0107-2024-021

Thanks to Nick Docken for MOTUS expertise and review.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.