Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

July 2025

How old is my bear?

Using a tooth to age animals

Bear hunters are curious about the bears they harvest in Alaska – as are wildlife biologists. Hunters are required to bring the hide and skull to a Fish and Game office for “sealing” (so named because a seal or tag is attached to the hide) and we gather information on the animal and the hunt. One important piece of that is the bear’s age.

Paul Converse in Douglas seals bears, which includes extracting a very small tooth which is used to determine the bear’s age. He offered me this suggestion: In spring and fall we have numerous bear hunters, and some moose hunters, ask about the process of aging an animal via the tooth sample, and our reply is always something like, “We send it to a lab and they count the rings. Like a tree.” It occurs to me that many hunters would appreciate a more-detailed explanation.

His suggestion is good, as is his basic explanation. As it turns out, Alaska wildlife biologists were among the scientists to develop and refine the technique, known as cementum age analysis. Back in the late 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, the department had its own wildlife lab in Anchorage for analysis of tooth sections from Alaska bears.

The rings in the tooth

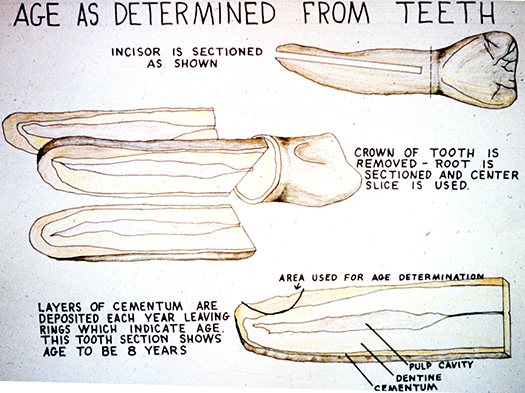

The “rings” in the root of a tooth are layers of a type of connective tissue, appropriately called cementum. Cementum surrounds the root of each tooth and interacts with connective tissues in the gums to anchor teeth in the mouth. It also aids in repairing damaged teeth.

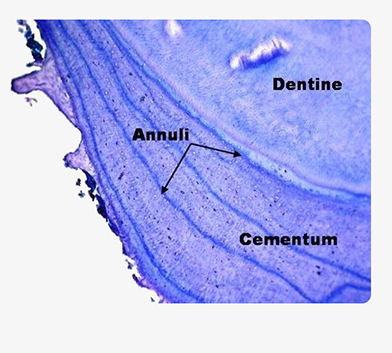

Throughout an animal’s life, cementum is continuously deposited over the root of the tooth, forming layers which appear as rings (also known as annuli). Cementum rings tend to coincide with seasons, appearing dark and thin during winter, when resources are scarce, and light and thick during spring and summer, when resources are more abundant (which fits with the tree ring analogy). This results in a microscopically visible pattern that is used to determine ages.

The cementum rings are more distinct in animals that live further north than their southern counterparts - likely because climate and resources are more uniform across seasons in southern regions but are more pronounced in the north.

Aging bears

Famed mountain man Grizzly Adams, an observant naturalist, noted the annual patterns in bear teeth in the 1850s. A century later the correlation between age and cementum layers was confirmed in other animals, and bear teeth were first examined to determine the age of a bear. In the 1960s, a wildlife biologist in Montana named Gary Matson began refining the technique - as did biologists with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Larry Van Daele remembers that work. In his 40-year career as a wildlife biologist with Fish and Game he worked with Kodiak bears and served as the Kodiak area biologist. He’s now retired and still lives in Kodiak. In the late 1980s he was in the Anchorage office, and he recalled the lab there and the biologists who worked on cementum age analysis.

“Enid Keyes ran the lab, which started around statehood,” he said. “They collected teeth from black, polar, and brown bears. Two bear biologists, Lee Glenn and Lee Miller, were some of the first ones to do it. Enid helped to expand it for practical use, in the late 1960s and into the 1970s. You know how it is, science builds on teamwork, and others had done some annuli work, they were not the only ones.”

In the 1980s, Alaska bear biologists Larry Aumiller and Harry Reynolds were active in the lab. At that same time, Gary Matson was doing the work commercially at his lab in Montana, Matson’s Laboratory. In 1988 the Alaskans invited Matson to visit the Anchorage lab to compare notes and analysis.

“He stayed at my house when we were doing this,” Van Daele said. “Gary Matson and I did some blind tests to determine how accurate their tests were. We got teeth from known-age bears and gave the teeth to both labs. I coordinated this with our lab, and he coordinated with his lab in Montana.”

Each lab received 100 samples, and each sample was “read” by biologists at each lab three times. The results were impressive, Van Daele said.

“We found out they were very effective at what they did,” he said. “It was more cost efficient to have them do it, and we closed our lab in the late ‘80s.”

Matson’s Laboratory

Matson’s Laboratory is in Manhattan, Montana, about 20 miles west of Bozeman. They do cementum age analysis for hunters and for scientists from all over the world, and age over 100,000 samples each year. Most of their work is with deer and bears.

I called and spoke with Lab Manager AJ Stephens. He told me they aged about 38,000 black bears last year - 2024 was a record year, he said, about 33,000 is more typical.

The top animals they age are black and brown bears, deer, moose, elk, bobcats, river otter, mountain lions and marten. They aged 2,000 martens last year. Other furbearers include wolverines and fishers.

“Any game animal or furbearer, we’ve done them,” Stephens said. “We did 62 different species in 2024.”

He said they also do marine mammals, including seals, walrus, and porpoise. “We did a 62-year-old beluga whale, that was the oldest animal we’ve aged here that I know. It was probably a little older because the tooth structure was worn down a little into the area where we were aging.”

Stephens has a bachelor’s degree in biology and started at Matson’s Laboratory in 2015. He said it was a year of training before he started aging teeth. “It takes about two years, maybe two and a half years to learn everything.”

He said while any of the agers can age any species, they tend to focus.

“We delineate by species, ungulates and carnivores. I’m one of the main carnivore agers.”

He and another skilled carnivore ager cross-check each other’s work. “The goal is at least 10% of the work, and anything you have a question on you highlight as you go through.”

Some species, like wolverines, are given to specific people, since they are best at aging those animals. “River otters are tricky,” he said. “River otters, mountain lions, and sheep are the hardest animals to age, I’d say.”

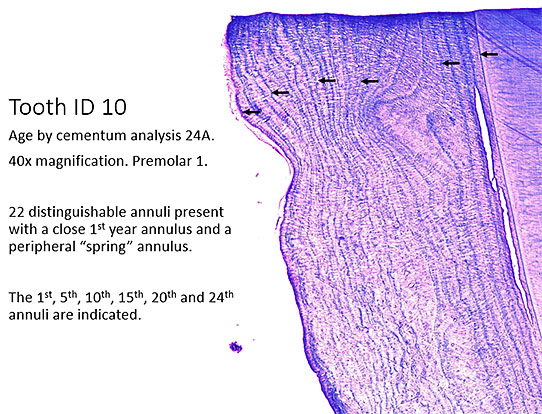

Cementum patterns vary between animals, and the best type of tooth for the cementum age analysis varies by species: in bears it’s the premolar, in bobcats it’s canines, and in ungulates it’s incisors. However, in the absence of these tooth types being available, any tooth can be processed and aged.

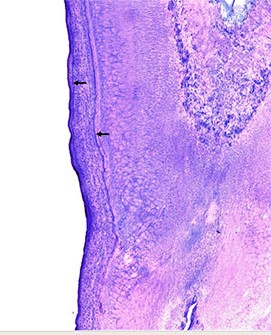

When teeth arrive at the lab, they are prepared for analysis – they’re cleaned, decalcified, and embedded in paraffin. Extremely thin sections of the root of the tooth are sliced, mounted onto glass slides, and stained purple to make the cementum annuli more visible under a microscope. The annuli are generally examined at 40-power magnification, and more densely packed annuli of older bears may be magnified 100-200 times.

Stephens said the annuli on black bears are pretty distinct and bears two to six years old tend to be the easiest to age.

“As they get older the annuli get compressed, makes it hard to see the separation,” he said.

They age brown bears that are into their late 20s, and even older. “We get them into their 30s, “he said. “The oldest bear I personally aged – I aged a 35-year-old black bear the year I turned 35, and that’s the oldest bear ever aged in Montana.”

“I also aged a walrus that was 34 on my 35th birthday,” he added. “It was taken the previous year, so we were born the same year.”

More

More on Matson’s Laboratory

More on sealing bears and why knowing the age of bears is important for wildlife management.

Sealing requirements (from the hunting regulations)

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.