Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

October 2010

Keeping Chronic Wasting Disease out of Alaska

A $5 bottle of deer urine could be two ounces of trouble for Alaska, and wildlife managers don’t want the product in the state.

Deer urine is possible route into Alaska for chronic wasting disease (CWD), a degenerative, fatal illness that affects deer, moose, and elk. The disease has not yet been found in Alaska, and wildlife managers are working to keep it out.

Hunters sometimes use deer urine as an attractant, or to mask human scent. It is sold in hunting supply stores, and through on-line catalogues.

“Although other states and provinces are enacting regulations, Alaska does not currently prohibit the import, sale or use of doe urine but should,” said Dr. Kimberlee Beckmen, a wildlife veterinarian with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. “By continuing to allow hunters to purchase deer urine collected or produced in other states which have chronic wasting disease, the disease could be introduced to Alaska. So far, there is no known method to eradicate the disease once it is introduced into a free-ranging cervid population.”

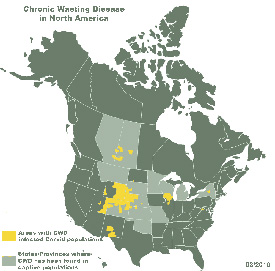

Cervids are members of the deer family, and CWD is spreading in cervid populations in the Lower 48. It has been found in free-ranging deer and elk (and in captive or farmed deer and elk) in 18 states and two Canadian provinces. In recent years CWD has also been detected in wild moose in Colorado and Wyoming. Evidence from genetics studies conducted in collaboration with ADF&G indicates that caribou are highly likely to be susceptible as well, although the disease has not yet been found in wild caribou.

There is no evidence that CWD can be transmitted to humans or domestic livestock, but the disease is a real concern for deer, moose and elk populations. CWD is caused by an infectious protein and is in the same group of diseases as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE or Mad Cow Disease). No treatment is available for animals affected with CWD, and there is no vaccine available yet to prevent CWD infection in deer or elk. Once clinical signs develop, the disease is invariably fatal.

The most obvious sign of CWD is progressive weight loss – thus the name chronic wasting disease. In addition to emaciation, classic clinical signs of CWD include wide stance, lowered head, droopy ears and excessive salivation. Although CWD has a long incubation period where no symptoms are apparent, once symptoms appear the clinical course varies from a few days to approximately a year, with most animals surviving from a few weeks to several months.

CWD has an extended incubation period – some 18 to 24 months on average between infection and the onset of clinical signs – and that makes controlling the spread of the disease more difficult. Infected animals may not show symptoms, and infected animals or animal parts may more easily be spread inadvertently. Another problem is the infectious agent – prions.

The disease is believed to be caused by abnormal proteins called rogue prions and it accumulates in the brain of infected animals. Prions are extremely resistant to degradation and can persist in the environment for decades in contaminated soil. Prions can also be found in deer saliva, feces and urine, and in the soil where an infected carcass decomposed or where infected animals lived.

David Phillips, a hunter who works at Rayco Sales, an outdoor shop in Juneau, said Rayco sells some scent attractants based on artificial ingredients, but none based on urine. He doesn’t think urine-based attractants are used much in the Juneau area. They are very popular in the Southern United States, he said, but the hunters he knows in Alaska attract deer by sound, not scent.

“Around here you wouldn’t want to be spreading that stuff around because of bears,” he said. “You might as well wear a hunting coat made out of steaks.”

A number of states and Canadian provinces have already banned the use of hunting products that contain fluids or tissue from any cervid. To prevent the spread of CWD, many also prohibit the transport of tissue and materials from cervids. Some body parts are particularly risky.

“Nearly all states, including Alaska prohibit the importation of ‘at risk materials’ from members of the deer family,” Beckmen said. “At risk materials are generally considered the brain, lymph nodes, and spinal cord. So any parts of the spine or skull must be cleaned of all tissue, and meat must be boned out to be allowed across state or provincial lines. Hunters they cannot take ‘at risk materials’ from their deer, moose, or caribou into other states or provinces, even though we do not have chronic wasting disease.”

At-risk materials have been responsible for introducing CWD to new areas. Beckmen said CWD was introduced to New York state by a taxidermist who was working on infected animals. The taxidermist was also hand-rearing orphaned deer fawns in the same workspace, and it is believed the fawns were exposed to infected materials and then released into the wild.

Once a deer or elk head has been completely prepared and mounted by a taxidermist, it is safe and legal to transport. Because the disease agents have never been demonstrated in cervid skeletal muscle, boned game meat is not considered an at-risk material.

Whole carcasses and at-risk parts from deer, elk and moose cannot be brought into Alaska. However, in addition to boned-out meat, wrapped or processed meat can be imported. A hide without the animal’s head is okay. A skull plate that is clean and disinfected; polished antlers with no meat or tissue attached; and a clean and disinfected whole skull (European mount) may be imported. Prions have been detected in velvet antler, thus antlers must be cleaned or polished to be imported.

Fish and Game has had a CWD surveillance program since 2003, supported by funding from the USDA. Hunters provided deer heads as tissue samples for examination, and road-killed deer, moose and elk were also collected and tested. Several thousand animals have been tested - as of Jan.1, 2010, 1,965 Sitka black-tailed deer, 91 elk, 55 caribou and 134 moose have been tested, all negative, with no positives detected in Alaska.

Wildlife technician Stephanie Sell works with the Alaska CWD surveillance program. Currently, the surveillance program focuses on testing ‘target’ moose and deer. These are animals that have clinical signs consistent with CWD such as emaciation, or are found dead. Road-killed moose in the areas near game farms, especially Palmer, Wasilla, Delta Junction, North Pole and the Kenai Peninsula are targeted.

Kodiak Island was the first focus in Alaska.

“The reason we started in Kodiak was there had been a large game farm there, with elk,” Beckmen said. “They had interacted with (wild) deer, and at one point the whole herd had escaped.”

There are a number of game farms in Alaska, raising bison, elk and reindeer. Farmed or captive deer and elk have played a major role in the spread of CWD. According to the USGS National Wildlife Health Center, CWD was first documented in a Colorado research facility in 1967. Over the next ten years, additional cases were documented in Colorado and Wyoming research facilities. The first detection in a free-ranging population was in Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado in 1981. CWD was first detected in farmed cervids in 1996 in Saskatchewan, and the source was tracked to a South Dakota facility; CWD was confirmed there in 1997.

Prior to 2000, CWD had been documented in only a handful of counties in southeastern Wyoming and adjacent northeastern Colorado. Since 2000 and after significant increases in surveillance efforts, CWD has been detected in many additional locations, and has continued to increase in prevalence in areas where it was known to exist.

For more information, see: http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=disease.cwd

Questions about CWD can be emailed to dfg.dwc.vet@alaska.gov

CWD map courtesy Chronic Wasting Disease Alliance

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.