Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

April 2011

The Gators and Bears of Spring

Managing Large and Potentially Dangerous Wildlife

In Alaska, spring brings bears. And sometimes they are where they shouldn’t be---in digging in dumpsters, eating dog food on your back porch, spreading your garbage all over your driveway, and even playing on your backyard swing set.

In Florida, spring brings alligators. They too are emerging from a dormant winter and looking for food and mates. Males, especially during the April mating season, move around a lot and account for most sightings.

Hungry bears and human foibles keep Alaska Department of Fish and Game biologists busy for months fielding nuisance bear calls, writing citations for improper garbage storage, and deciding when a particular bear has run out of second chances and needs to be destroyed. In Florida, a similar situation plays out with alligators. Despite the wide geographical and species divide, wildlife managers in both states face many of the same issues helping people coexist with these large, wild, potentially dangerous animals. Both species are dormant in winter and emerge in spring hungry and needing to put on a layer of fat.

Florida has over a million alligators, averaging between 3 and 8 feet in length - but they can grow up to 14 feet long and weigh 1,000 pounds. As they are cold blooded, they are most active during the warmest parts of the year---spring, summer, and fall. Alaska is home to about 100,000 black bears and about 30,000 brown bears, also called grizzly bears. Alaska’s black bears average about 200 pounds, brown bears and average 350 to 500 pounds, and big coastal bears can be more than 1,000 pounds.

Steve Stiegler, Assistant Leader, Alligator Management Program, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, estimates he receives about 15,000 calls a year about alligator sightings. “Most of the calls we get are from people observing alligators in their natural setting, from their property,” Stiegler said. “Practically everyone in the state lives near a water body, and if someone is new, not from the region, when they see an alligator they kind of freak out.”

Unlike bears, which are curious and inquisitive, most alligator sightings are of alligators moving from one aquatic environment to another. “They don’t specifically go on land to search for food,” Stiegler said. That they may pass through your backyard or accidently wander into your garage is incidental; if left alone, most will continue on their journey. Along their overland journey, any feeding will be opportunistic and will most likely involve tethered animals or carcasses. “If someone ties up their dog next to a canal or lake a large gator might see that as easy pickings,” Steigler said.

To have an alligator hanging around purposefully in your house or yard is rare, according to Steigler. In contrast, many Juneau residents have stories of home visits by curious bears. Beth Potter of Basin Road woke up from a nap a few years ago and found something large and black in her living room. Her first thought was “Oh my god, there’s a big dog in my house.” It was actually a bear. “I almost could have reached out and touched him.” She stood up and yelled and the bear ran outside, much to the amusement of passing tourists. A few hours later, in her back yard, she felt like someone was watching her. She was right. “I looked around and he was behind a big spruce tree about 25 feet away staring at me.” She stood up and yelled and he left, but not before giving her a look she characterizes as “Wait, what did I do?” Despite making the bear look sad, “I didn’t want him to think it was cool to be there,” she said.

Bears are endearing, especially cubs. It’s easy to see how the unwary can be tempted to feed them, get close to take pictures, play with them, or otherwise treat them like pets. Their movements and mannerisms can appear surprisingly human, as many have discovered at the Mendenhall visitors center viewing platforms in Juneau. It’s not unusual to see cubs in trees sitting on branches and swinging their little legs like children. Conversely, alligators are not really anthropomorphized and no one thinks they’re cute, but the sure path to both species’ demise as nuisance animals starts with humans feeding them.

“Keep Alaska’s Bears Wild” - Alaska’s public service campaigns entreat people to secure their garbage in bear-proof containers, keep pet food indoors, and take down bird feeders.

The road to death for nuisance animals starts with access to human food or edible waste. In Southeast Alaska, several communities had problems with bears feeding at their landfills. According to Sandra Woods, Environmental Program Specialist with the State of Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation, many of these communities found that shipping their solid waste to Washington state solved their bear problems. “The last time I was in Klawock, there were no bears in the landfill,” she said. Other Southeast communities that have reduced their nuisance bear problem by shipping out their household waste are Ketchikan, Petersburg, Sitka, and Wrangell. This year, Yakutat will be testing a bear-proof electric fence around their landfill.

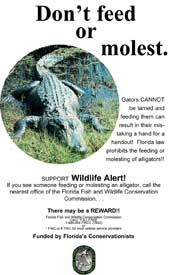

Florida’s public service educational campaigns stress “Don’t feed or molest.” Typical instances of alligator molesting involve people capturing a baby alligator, or trying to snag one with a fishing hook. “They’re only about 8 inches long as babies,” Stiegler said. People think it’s cool to have an alligator, not realizing that keeping one as a pet is illegal. Even a children’s coloring book “All About Alligators” available on the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation commission web site repeatedly stresses to children the importance of not feeding alligators.

It is illegal to feed alligators or keep them as pets---for the same reasons those activities are illegal in Alaska. Animals habituated to humans and domestic food sources---while exciting at first---often ends in tragedy with the animal first becoming a nuisance and then a danger to people, property, or pets. Both bears and alligators can difficult to relocate, as both usually return to their initial capture site.

What happens to nuisance animals?

Destroying nuisance bears is almost always the purview of Alaska Department of Fish and Game biologists. “It’s rare to have law enforcement destroy a bear without Fish and Game involvement,” said Ryan Scott, wildlife biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game in Juneau. In contrast, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission contracts licensed trappers to capture nuisance alligators. Each area has a trapping contractor who is required to make a site visit to the area of a legitimate nuisance alligator call. If the alligator is larger than 4 feet long, the trapper is allowed to kill it and sell the hide and meat for profit, which is how Florida’s licensed trapping contractors are paid. If the alligator is less than 4 ft long, it is relocated. Of the 15,000 calls received each year, only about 5,000 alligators are deemed a nuisance and removed.

“Alligator hide is a luxury product,” Stiegler said, and added “The hide market is depressed right now, along with the global market. The meat market is a novelty market, trappers probably get between $5 and $6 a pound selling to restaurant or seafood markets. When prices are high, all nuisance [alligator] trappers are fairly compensated.”

Alaska Department of Fish and Game biologists euthanize nuisance bears after first immobilizing bears with capture drugs. Scott explains “Per protocol, we use drugs to capture bears. It’s more humane.” Because of the drugs, the meat cannot be harvested for consumption, but the hides, bones, and skull are saved for requests from groups looking for bear hides and bones. ADF&G will permit the possession of bear parts for civic groups, schools, Native American organizations, and other groups with legitimate educational uses of the animal.

Risk to humans?

Florida’s 1.2 million alligators are found in all 67 counties. Despite the steady human population growth, now at just under 19 million, unprovoked bites by alligators have remained steady at only five per year between 1948 and 2004 with only 15 fatalities. Bear populations are not closely tracked; Alaska is too vast for precise counting. The population is managed for hunting, and neither brown or black bears have ever been endangered.

Humans are seldom the intended prey for either alligators or bears. Both may charge defensively if threatened, but neither are usually a threat unless guarding their young. Nest-guarding female alligators will sometimes hiss and open their mouths to frighten intruders, but it’s unlikely you will find yourself being chased on land by an alligator. Alligators are opportunistic feeders; they do most of their hunting by ambush in aquatic environments.

Humans are seldom intended prey for wild bears either, unless their natural fear of humans disappears once they associate humans with food. In the last decade, public service announcements, the availability of bear-proof garbage containers, and other awareness campaigns have helped curb the incidence of “garbage bears.” In the Juneau area, although number of nuisance bear calls averages around 100 per year, nuisance bear mortality has declined each year.

Amy Carroll is a publications specialist with ADF&G, covering the shark and alligator beat for Alaka Fish and Wildlife News.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.