Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

October 2012

Back to Mahoney

A Special Mountain Goat Hunt

“Dad,” Trevor whispered, “there’s a goat!” Sure enough, less than 200 yards from our tent we could just make out the top of a goat’s back as it fed upslope amidst a bed of deer cabbage and crow berry. “Grab the camera,” I instructed, “and I’ll get the binocs.” Hunched over to stay hidden behind the small, bushy mountain hemlocks, Trevor and I hustled up the mountain a hundred yards and then moved slowly and quietly east along the hillside towards the goat’s location. Crawling on hands and knees, we peeked over a small hillock and caught sight of it, less than 30 yards away. The goat was oblivious to our presence as I put the binoculars to my eyes. “It’s a small billy,” I whispered, “about 2 ½ years old I’m guessing.” We watched as the goat fed for several minutes, intermittently flipping its ears and tossing its head to shake free of the flies that buzzed about it. Trevor took a few pictures and a short video clip. At some point the camera caught the goat’s attention and it locked its eyes on us. After staring at one another for a few seconds the goat got nervous and moved tentatively down slope, pausing occasionally to look back in our direction. Eventually it disappeared over the edge of the mountain and into thick brush.

“Wow, that was cool,” I commented. Trevor agreed. It was the closest he’d been to a goat in his life and the experience was clearly a memorable one. I offhandedly mentioned that we were easily close enough to take the goat, either with a bow or rifle, had we not flown that day. We had been dropped off in Upper Silvis Lake a few hours earlier in a de Havilland Beaver and we wouldn’t be legal to hunt goats until the following day. No matter, seeing the goat up close and watching it feed, shake off bugs, and scratch itself with its hind hoof provided ample satisfaction.

For Trevor and me, the goat hunt began when I was drawn by the State to participate in DG006, the drawing permit hunt located behind Ketchikan on Revillagigedo (commonly known as Revilla) Island. I had put both his name and mine in for the drawing but, despite my hope that he would be the one drawn, luck had favored me this time. The hunt would be special. Twenty-one years earlier, in August 1991, I had led the effort to introduce the original 15 mountain goats from the Quartz Hill area of Misty Fjords to Upper Mahoney Lake on Revilla Island. I was serving as the local area wildlife biologist for the Department of Fish and Game at the time, living with my family in Ketchikan. Trevor had been just 10 months old when our team of staff and volunteers took to the sky and sea on that sunny August 10th to capture, transport, and release the goats on the island.

At the time of the introduction I had worked closely with staff from the U.S. Forest Service, with leadership of the Ketchikan Sports and Wildlife Club (who proposed the introduction), with Dr. Vern Starks, Ketchikan’s local veterinarian, and with a slew of local volunteers. After many months of discussion, a public meeting, and a couple of evening planning sessions with the transplant team at the Fish and Game office conference room, we were ready to put the plan into action.

August 10, 1991 dawned clear and sunny, though patches of fog briefly threatened to interfere with our operation. Thankfully, the little bit of fog that formed initially was burned off by mid morning, allowing us to get into the mountains to search for goats. The machinery involved in the project was nothing short of impressive. We had three Hughes 500 helicopters, one piloted by flying legend and founder of Temsco Helicopters, Ken Eichner, another by Bob Hite of South Coast, Inc., and a third by Steve Seley, owner of South Coast. I flew with Ken in one of two capture helicopters and LaVern Beier, our Fish and Game technician out of Juneau flew with Bob in the other. Local photographer Steve Shrum flew with Seley as the project photographer, and Two Bell 206 Jet Rangers, owned by Ketchikan Pulp Company and piloted by Allen Zink and Cliff Kamm, transported captured goats from Pete Amundson’s processing barge in Smeaton Bay to the release site at Upper Mahoney Lake. A Cessna 185 piloted by Miles Enright and a Piper PA-12 piloted by Allen Jones flew to locate goats and give locations to the capture crews. A Forest Service-leased Hughes 500 transported a crew of reporters/photographers from KTOO in Juneau (a Rain Country episode was subsequently produced by KTOO about the transplant).

Several volunteers worked aboard Pete’s barge to keep captured goats cool, cover their eyes with blindfolds to lessen their stress, cover their horns with rubber hose to prevent them from poking holes in aircraft fabric or volunteers’ flesh, ear-tag each animal, and place a radio collar on seven of the goats (two billies and five nannies). Once delivered to the release site, another group of volunteers worked with Dr. Starks to administer antibiotics to combat any pathogens or infections the goats may have, and then administer the antagonist drug that brought goats out of their drugged state and allowed them to become mobile and walk off into the scrub timber and up the slopes of the lake’s bowl. At the end of the day, we had captured and introduced 10 nannies and 5 billies. Ages and weights of the introduced billies ranged from 4-8 years and 150-245 pounds, and for nannies 2-7 years and 85-166 pounds. I calculated at the time that the cost for the one-day effort would have amounted to a little over $47,000, had the aircraft, tug, barge, other equipment, fuel, and time not been donated. It was a truly phenomenal and generous community effort.

Four months after the release, a 7 year old nanny was found dead on a mountain snowfield above Ketchikan. The animal’s radio collar, with its programmed mortality signal, led us to its location. Its cause of death appeared to be starvation. A second mortality, this time a 10 year old billy, was also detected as a result of the goat’s collar in April 1994. This goat had likewise succumbed to winter starvation. No further mortalities were detected during the time the radio collars’ batteries remained active. A subsequent aerial survey I conducted in fall 1998 resulted in a count of 59 goats. And now, 21 years later, Trevor and I stood together, watching the young billy, a distant relative of those originally introduced, wander off into the woods. Wow, pretty special!

We were up early the next morning and climbed the ridge to the top of Mahoney Mountain. There, as we snuck over the top, we came upon a goat that rose from its bed when we approached. We lowered ourselves slowly and quietly to the ground. Trevor put the range finder on the goat while I assessed it through binoculars. “Seventy-five yards, Dad,” Trevor informed me. “It’s a nanny,” I replied, “and an old one.” The nannies’ horns appeared to be at least 10 inches in length, long for any goat. Nonetheless, knowing the importance of nannies to goat population growth and stability and the desire to focus harvests on billies, I passed up the nanny, despite the fact she didn’t have a kid and was legal to harvest.

Satisfied that we meant her no harm, the nanny bedded back down in a dirt-filled depression. We watched her for several minutes as the rising sun backlit her with streams of red and orange light. Trevor took a couple photos and then we slowly and deliberately eased back over the top of the mountain and continued our search.

We hiked northward along the ridge of Mahoney Mountain until we found ourselves looking down into Upper Mahoney Lake. “There, Trevor, in that small bowl on the north side of the lake, that’s where we released the goats.” Trevor looked down. “Hey, we should take a picture of both of us with the release site in the background,” Trevor suggested. “Good idea,” I replied. Trevor set the camera on a small tripod, programmed the self-taker, and joined me in the photo.

We continued north along the ridge of Mahoney Mountain, dropping down off the steep north end and crossing a stream running with clear, clean snowmelt. We filled our water bottles and then climbed up onto the northwest flank of John Mountain where we spotted 17 goats, mostly nannies and kids, but also a lone goat bedded on a steep cliff overlooking the Ketchikan Lakes bowl, likely a billy. Looking northeast, we spotted another group of 16 nannies and kids about a mile away. They were streaming southward over the top of the ridge north of Upper Mahoney Lake. Trevor and I debated whether to climb the flank of John Mountain with its steep, snow-covered slope, but ultimately decided to retrace our steps and follow the northwest edge of the lake separating Mahoney and John mountains. It was a beautiful day and the glare off the snowfields was intense as we crossed them enroute back to our camp.

While relaxing in camp we were visited by Ketchikan residents, Kerry Watson and Al Murray, who were in the process of hiking the 13 mile route from Deer Mountain to Beaver Falls. We chatted for a few minutes and they shared with us that they had seen over 60 goats during their trek. They commented how great it was to be able to see and enjoy goats so close to town. I shared with them that Boyd Porter, Fish and Game’s Ketchikan wildlife biologist, had indicated to me that he’d seen over 180 goats during a recent area-wide survey. Knowing that not all goats are seen during surveys, it was fair to assume that well over 200 now resided on the mountains north of Ketchikan. Pretty impressive considering the meager beginning of 15 goats, and a far more successful outcome than I had anticipated 21 years ago!

Trevor and I spent the evening glassing the mountains from camp and observed eight goats on the south and east sides of John Mountain. We decided to forego pursuing them in lieu of scouting the southeast side of Mahoney Mountain. With the evening light fading, Trevor suddenly pointed upwards at the side of Mahoney. “Look, Dad, goats.” Indeed, we could see four goats feeding northward along the upper flank of the mountain. Grabbing our rifles and gear, we scurried up the mountain, crossed a snowfield in a small saddle, and snuck through rock rubble until we lay on our stomachs in a patch of crowberry. Glassing the goats, we determined there were three nannies and a kid. For ten minutes we enjoyed watching them feed. As they disappeared behind a bluff, we turned and retreated back downhill to camp.

As we were finishing dinner in the growing darkness, Trevor suddenly whispered excitedly, “Dad, there’s a goat!” Looking uphill, I could just make out a white form. I brought my binoculars to my eyes and confirmed that it was indeed a goat, and it was standing broadside to us. “Two hundred fifteen yards,” Trevor whispered. Clearly within range, I needed to determine whether it was a billy or nanny. My eyes caught movement to the side of the goat in question. I glassed it; a kid. Trevor and I watched as the two disappeared into the darkness.

Minutes later, we slipped into our sleeping bags, with our heads sticking out of the tent so we could look up at the brilliant star-filled sky. “Whoa, look at that shooting star,” Trevor exclaimed as we stared skyward. I too had seen the bright star shoot across the sky; the brightest and most pronounced either of us had ever seen. “I read somewhere recently that this month and next are supposed to have more shooting stars than have been or will be seen in a long time,” Trevor told me. “Interesting,” I replied. A nearly full moon showed itself, adding ambiance to an already incredible evening. Looking up at the sky, we chatted for several minutes about various things, including the awesome day we’d shared, before finally drifting off to sleep.

I awoke at 4:15 to the sound of a ptarmigan cackling nearby. At 5:00 I crawled out of my bag and got dressed. By then a second ptarmigan had joined the first and the two stirred up a cacophony of clucking and cackling, taking to the air and then landing to begin the chorus all over. This continued for several minutes. In the meanwhile, I took a moment to scan the hills in the dim morning light. A movement caught my eye and on closer inspection I realized a goat was feeding upslope about 100 yards east of our camp. “Trevor,” I whispered, “there’s a goat where the little billy was the other night.” Trevor scrambled out of his bag and into his clothes and the two of us snuck through a thicket of mountain hemlock and side-hilled across a patch of deer cabbage. Peeking over a small mound, we spotted the goat, a scant 30 yards away. Through my binoculars I determined it was a nanny. “Look,” Trevor whispered, “a kid too.” Sure enough, another nanny and kid, perhaps the same ones we’d seen the night before in dim light. We watched the pair for a few minutes and Trevor snapped a couple photos. Unintentionally, the flash went off on one photo, which caught the nanny’s attention and she locked eyes on us. The kid remained oblivious to us. After looking our way for a few moments, the nanny became nervous and slowly began moving away, her kid following dutifully but ignorant to our presence. Trevor caught one last photo as the two crested a ridge, stood silhouetted briefly, and then disappeared.

Back in camp I noticed a thick fog bank building to the southeast of us. As we boiled water for oatmeal and coffee, we watched as the fog moved rapidly in our direction, pushed by a growing and steady breeze. Like boney fingers, the fog enshrouded the ridge and peaks of Achilles Mountain before pouring into the deep Silvis Lake valley. “Here it comes,” I observed to Trevor as the fog swept upward and over us. With astonishing speed our clear sunlit ridge was transformed into a damp, gray, soup-like cloak. Visibility shrank to less than 50 feet. “I think this is going to last a while,” I said to Trevor. “Feels like the predicted rain will settle in as well,” I added. Given the circumstances, and with impending commitments back home, we decided to pack up and head down the mountain. By 8:00 we had shouldered our packs and begun the 6-mile descent.

With the fog compromising visibility, we made our way slowly. In places I would stop and wait for Trevor to scout ahead to relocate the trail before leaving the segment we knew to be part of the trail. Flagging and markers along the trail were helpful and appreciated. We dropped down off the alpine ridge into the subalpine scrub forest before entering timbered old-growth forest. The fog thinned but rain persisted as we descended. As we approached Upper Silvis Lake we were greeted by the sound of a dog barking and soon after spotted the dog as well as a man working to improve the trail. Approaching, we hailed the man and learned his name was Jon Swada. I had worked with his wife, Leslie, years ago on field projects when she was working as a wildlife technician for the Forest Service. Though Jon and I had never met, he said he knew me by reputation as the guy who had introduced the Mahoney goats. He and two others had been contracted by the Forest Service to improve the Silvis Lake trail and Trevor and I shared our appreciation for the great job they were doing.

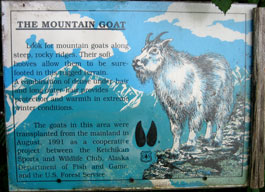

As we continued down the trail to Beaver Falls and our ride into Ketchikan, Trevor observed that it was funny that even people I didn’t know personally knew me by name as the guy who spearheaded the effort to bring goats to Ketchikan’s back yard. At Lower Silvis Lake we observed a sign commemorating the transplant. We stopped to take photos by it.

So ended my return to Mahoney and the site of the 1991 goat release. Though we had no goat in our packs to show for our efforts, Trevor and I had something far greater. We had the experience of sharing together an incredible homecoming, and to see the phenomenal success of the collaborative effort that had taken place 21 years earlier; an effort I had been privileged to be part of. “Boy,” I offhandedly quipped to Trevor as we walked the final quarter mile to the truck, “I’m sure glad we didn’t ruin a perfectly good hunt by shooting something!” Trevor laughed.

Wildlife biologist Doug Larsen serves as the Regional Supervisor for the Division of Wildlife Conservation in Southeast Alaska.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.