Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

August 2016

Ten days at the Alcan Border

Trailered watercraft as a Pathway for Invasives

Who doesn’t like to get out of Alaska for a quick dose of sunshine in the Lower 48 or somewhere else when our early spring days are short and the snow is still low on the mountains. Then, as the days warm and lengthen, like salmon returning to their natal streams, residents and visitors alike start making their way to Alaska for the beauty, the fish, the wildlife or because it’s home.

Early this May, I had the opportunity to glimpse the human migration to Alaska. If you’ve traveled the Alaska Highway, through the Yukon Territories from other Canadian provinces or the Lower 48, you know the welcome sight of the Alcan Border Station. The scenery is unbeatable at that vantage with the Wrangell and St. Elias mountain ranges in view on a clear day; wetland lakes reflect the surrounding hills, and breeding pairs of tundra swan nest along the shorelines. Native northern pike and coho salmon can be caught in lakes by walking a quarter mile or more off the highway, while Arctic grayling inhabit clear streams you can access from the roadside. Great predatory birds like great grey owls and bald eagles fly overhead. It’s easy to understand why there are lines of cars at the border. As they passed through, I often heard drivers say, “It’s great to be home!” But I wasn’t there for the scenery.

Over a ten-day period this spring, I watched cars, trucks, and recreational vehicles with their canoes, kayaks, and trailered pleasure boats streaming through the Port of Alcan. I was there to observe how many and what types of watercraft entered the state. I was also available to provide technical assistance to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agents involved in “Operation Northern Creep,” an effort to address the threat of invasive species entering Alaska on boats brought in through the Alcan border. Watercraft are a key way aquatic invasive species are transported from infested waterbodies across the continent, and natural resource agencies want to prevent their introduction into Alaska waters.

According to the National Invasive Species Council, an invasive species is an organism not native to the ecosystem under consideration, whose introduction causes or is likely to cause economic or environmental harm, or harm to human health. Two aquatic invasive species Alaskans may have heard of are northern pike and Elodea. Northern pike, while native to Interior Alaska, were illegally introduced into waters of Southcentral, causing population declines of Pacific salmon and resident fish species and resulting in reduced sport fishing opportunities. The common aquarium plant Elodea has been detected in water bodies around Fairbanks, Anchorage, Cordova, and on the Kenai Peninsula. Both of these introduced organisms endanger aquatic ecosystems and their food webs, which means fewer recreational and economic opportunities for anglers, boaters and floatplane pilots. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game, the Department of Natural Resources, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have cooperatively put their shoulders to the wheel to address to aquatic invasives species in Alaska. Response actions include educating the public about aquatic invasive species, partnering with local governments and organizations to monitor hundreds of lakes and rivers, and collectively eradicating invasive northern pike and Elodea from numerous freshwater systems.

In 2008, preliminary research suggested that the low-end annual cost to the Great Lakes region from aquatic invasive species introduced by shipping could be upwards of $200 million a year, because invasions limit the ability of natural ecosystems to support commercial and sport fisheries, raw water uses, and wildlife watching. Though seemingly disconnected from Alaska, the Great Lakes region is where zebra and quagga mussels were first introduced to U.S. waters in the late 1980s. Twenty years later, these mollusks from the Dreissenidae family (dreissenids) made their way across the country to Colorado, Utah, Arizona, Nevada and California. An evaluation, completed in 2010, of potential economic costs from invasive mussel infestations of the Columbia River Basin in the Pacific Northwest estimated a one-time cost of $21 million with an ongoing annual cost of $26 million. Without connecting waterways, how did dreissenid mussels get translocated hundreds, if not thousands of miles to the west coast, causing environmental and economic impacts in their wake?

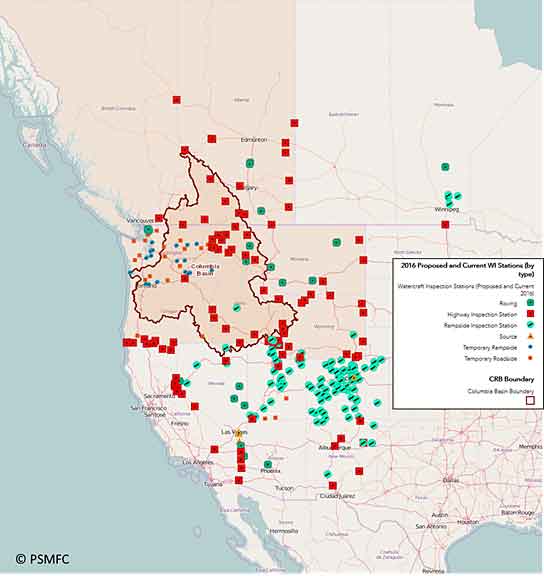

By the early-2000s, natural resource agencies understood that the overland movement of watercraft (e.g. boats on trailers, canoes and kayaks on cars) from invasive species infested waters could result in new introductions. Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission (the Commission) recognized recreational watercraft from the Great Lakes region were carrying both adult and larval stages of invasive dreissenid mussels and other aquatic invasive species to western freshwater systems on their hulls, in ballast tanks and in compartments. This pathway posed risks to the aquatic habitats and fisheries of the west. Consequently, the Commission developed protocols and standards to inspect and decontaminate watercraft, thereby reducing the chance zebra or quagga mussels could survive transport and be introduced into another water body. Today, most western states and Canadian provinces inspect watercraft either upon entering their state or province, or before allowing boats to launch. To be sure, states have various ways of implementing their aquatic invasive species programs; however, all states that inspect watercraft follow the same protocols and standards that were developed by the Commission. Back at the Port of Alcan, I was available to assist the Fish and Wildlife Service if questions arose about implementing the protocols and standards of watercraft inspection and decontamination.

During my stint at the border, the Fish and Wildlife Service was operating a “roving” or temporary watercraft inspection and decontamination station. I watched as they asked individuals carrying watercraft on trailers or atop their vehicle to stop after having cleared Customs and Border Protection. Once stopped, the driver was asked where and when the boat had last been in the water. This information allowed Fish and Wildlife Service to determine the level of risk the boat posed. High-risk watercraft are those that have been in an infested waterbody or a state considered positive for invasive zebra or quagga (dreissenid) mussels in the previous 30 days. Other high risk factors include “dirty, crusty or slimy” hulls, presence of standing water, and watercraft with ballast tanks and internal compartments because of their ability to hold water for long periods of time. If a boat was found to fit these descriptions, Fish and Wildlife Service asked the boat owner for permission to conduct a thorough inspection of their boat.

According to David Wong, a researcher at University of Nevada at Las Vegas, “People don’t realize how resilient these mussels are.” He’s found that larval mussels (mussel babies) can survive on a boat out of water for as long as 27 days! It certainly doesn’t take 27 days to travel to Alaska from infested waters in the Lower 48 or Canada, even if coming from the heavily invasive species infested Great Lakes region. If mussels can survive out of water for 27 days, imagine how well they do in the moist nooks and crannies of a motor or the internal compartment of a boat.

The Tetlin National Wildlife Refuge headquarters located near Tok, Alaska provided the Fish and Wildlife Service team with a hot water pressure washer to decontaminate any boats that needed it. According to research completed by Comeau et al. and published in the journal Biofouling in 2011, hot (120° when flushing or 140°when applying direct contact), pressurized (3,000 psi) water has been proven to effectively kill adult and veliger (juvenile) mussels on or in recreational watercraft. Aside from allowing a watercraft to completely dry for 30 or more days, hot pressurized water is the silver bullet for eliminating invasive dreissenid mussels on watercraft.

During the period of May 6 – 16, 2016, the Fish and Wildlife Service operated an inspection station between 8am and 8pm, inspecting 10 boats per day on average, with a total of 95 watercraft inspected overall. The public seemed to have some knowledge about aquatic invasive species. To increase their understanding outreach materials about the issue were distributed. A few of the boats that stopped at the inspection station had previously been inspected in Wyoming, Idaho, or in the province of British Columbia. Of a sample of 27, watercraft were reported from 17 states and one province, and 13 watercraft were from states with infested waterbodies. One vessel had standing seawater, so to eliminate any risk the plug was pulled and the boat drained. A canoe with loose gravel inside was inspected for New Zealand mudsnails. During the inspection period no zebra or quagga mussels were detected in or on any of the watercraft, and the pressure washer went unused.

After ten days observing watercraft entering the state I now have a glimmer of insight as to where boats are arriving from. I learned that high-risk boats are entering Alaska. Since, at this time, there is no known method for controlling or eradicating zebra and quagga mussels once they have become established, prevention is still the best and most cost effective way to protect our waters from aquatic invasive species.

What can I do?

Watercraft owners can be good stewards of the waters where they love to recreate when they “Clean, Drain and Dry” their boats, equipment, gear and even pets. We all should take extra time at the boat launch to check for and remove any lingering plant material, sediment or mud on the motor, hull, inside the boat or on the trailer. Remember to pull the plug and allow all standing water to drain out of the boat and compartments. After disposing of garbage and left over bait in an appropriate waste receptacle dump and rinse out any standing water in buckets or coolers before you leave the area. Keep a sponge or rags in your watercraft to wipe off remaining water. These are the easiest ways to avoid moving aquatic invasive species and to insure you are part of the solution. Call the Department of Fish and Game if you have questions about how to Clean, Drain and Dry. Please help keep Alaska free of all invasive species by taking time to inspect yourself and your gear before you visit and before you leave water bodies and recreational areas. Alaska is a big state, we need your help! Please report all suspected or known invasive species by calling 1-877-INVASIV (1-877-468-2748).

Tammy Davis is the coordinator of the Invasive Species Program, with the Division of Sport Fish.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.