Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

September 2016

Alexander Creek and the Impacts

of Illegal Introductions of Northern Pike

Northern pike are native to Alaska, both north and west of the Alaska Range. Where they are native, they are considered a prized, sought after fish - both because of their size and voracity, and also because their flaky white flesh makes for excellent table fare. However, in areas where they are not native and have been illegally introduced they are capable of creating catastrophic impacts to native fish and animal communities.

Northern pike were illegally introduced to the Susitna drainage of Southcentral Alaska sometime in the early 1950s. This system encompasses tens of thousands of square miles and is roughly the size of the state of Indiana. The Susitna drainage system is comprised of glacial rivers, hundreds of both fast and slow flowing clearwater tributaries and side-slough channels, along with hundreds of interconnecting shallow lakes and ponds, large deep-water lakes and thousands of acres of adjacent wetland areas. The spread of pike in this drainage was fairly slow through the mid-1980s, however, since the 1986 flood pike have rapidly expanded their range and can now be found throughout the Susitna drainage. The bulk of the Susitna’s salmonid production takes place in the numerous fast clearwater streams and large deep clearwater lakes that support little or no pike habitat. In these waters, predation impacts by invasive pike are negligible. However, several tributaries support vast expanses of pike habitat where overlap between salmonid and invasive pike habitat can lead to over 90 percent predation on juvenile salmonids. Pike predation has had catastrophic impacts on salmonid communities, so much that pike biologist consider these systems as “pike factories”, one of which being Alexander Creek.

Northern pike were first illegally introduced into Alexander Lake sometime in the mid to late 1960s. Over the past 30 years, pike have slowly moved downstream and are now found throughout the entire drainage. Alexander Creek, with its headwaters about 100 feet above sea level, flows at a low velocity with numerous oxbow and side-slough channels. It also has large amounts of instream vegetative mats, shallow interconnecting lakes and ponds and tens of thousands of acres of adjacent wetland areas, all of which support exceptional pike spawning, rearing, and nursery habitat.

Prior to complete encroachment by pike, Alexander Creek supported some of the largest king (Chinook) and silver (coho) salmon returns in the entire Northern Cook Inlet area. Since then, king salmon numbers dwindled from a high of 6,300 in 1989 to a low of less than 150 in 2008; silver and red (sockeye) salmon numbers displayed similar trends. Salmon returning to Alexander Creek once supported a significant portion of Cook Inlet subsistence and commercial fisheries. Resident fish populations such as rainbow trout, Arctic grayling and burbot, long nosed suckers and whitefish declined as well. Chinook salmon once spawned throughout the entire mainstem of Alexander Creek including upstream of Alexander Lake. Since pike encroachment, nearly all the salmon spawning is confined to a fast clearwater tributary of the creek known as Sucker Creek. Alexander Creek once supported a multimillion dollar sport fish industry with ten full time lodges, along with numerous guides, air and boat charter services, and boat rentals - all which are no longer in operation since the king salmon fisheries plummeted.

The king salmon sport fishery in Alexander Creek has been restricted since 2002, closed to sport fishing since 2008 and was declared a stock of concern by the Alaska Board of Fisheries in 2011. This has taken an economic toll on both a local and regional level. Alexander Lake at the headwaters of Alexander Creek was once a productive waterfowl production area. Now, a person is lucky to observe a clutch of ducks with more than one surviving offspring. The lake use to support hundreds of muskrat caches and feeder piles where local residents were able to subsidize their incomes from trapping. Today, few if any muskrats are observed in the lake.

Northern pike are a prolific species in that their fecundity (number of eggs per fish) can attain more than a quarter million eggs from just one large female. Northern pike are a very hearty species of fish; tolerating fairly saline environments and thrive in waters with low oxygen levels. Under the right conditions northern pike can survive for several hours out of water so they are easy candidates for illegal stocking or transplanting activities. This has been a huge contributing factor in the spread of invasive pike not only in Alexander Creek but also to numerous other locations in Southcentral Alaska.

Concern over diminished king salmon numbers in Alexander Creek along with other salmon species and resident fish populations such as rainbow trout and Arctic grayling prompted the department to initiate an Alexander Creek pike suppression program. The primary goal of the program is to restore Alexander Creek salmonid populations to some semblance of historic levels by removing up to 80 percent of the invasive pike population in the sloughs and side-channels of the creek. This program was a multi-faceted project which included pike suppression/removal, radio telemetry, pike dietary analysis and adult and juvenile salmonid monitoring.

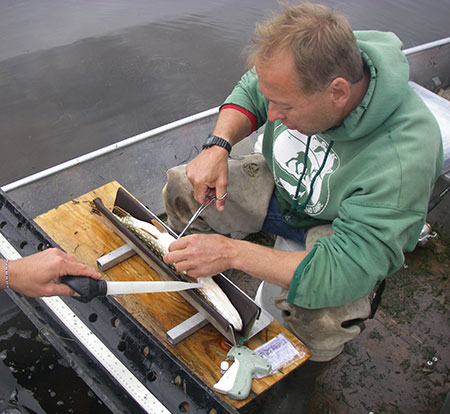

Suppression efforts commenced in the spring of 2011 and are ongoing. Each spring - depending upon water level - up to 62 side-slough channels of Alexander Creek are intensively netted using variable mesh gillnets in a 40-mile stretch of Alexander Creek in an effort to remove as many invasive pike as possible. To date, more than 18,000 pike have been removed. In June 2011, in an effort to determine if northern pike were migrating from the creek into the lake or vice versa, 150 northern pike were captured and surgically implanted with radio transmitters. Aerial surveys were flown once or twice monthly to document individual fish movements. This effort was conducted to determine if it would be necessary to expand the suppression efforts to include Alexander Lake. If it was determined that a large number of pike were leaving the lake to spawn in the creek the cost of the project would have likely doubled.

Information from radiotagged fish indicated that few pike migrated out of the lake. The few that did were captured by gillnetting crews during spring suppression efforts so it was not necessary to extend our suppression efforts to the lake. This was a huge cost saving measure.

In order to gauge current and long-term success of the northern pike suppression efforts, a crucial component of the project was to monitor adult salmon returns, resident fish production, and assess juvenile salmon production and distribution behavior. The adult salmon monitoring portion of this study was initiated primarily to document increases or decreases in adult salmon abundance as a key indicator for overall project success. King salmon were monitored via aerial survey’s to document the number of spawning fish and to assess if there has been any re-colonization of historical spawning areas in the mainstem of the creek. Other salmon species and resident fish were monitored via anecdotal observations from king salmon surveys, catch and harvest trend information generated from the departments Statewide Harvest Survey along with reported information from local and area residents and sport fishers.

Juvenile salmon production was measured using minnow traps in concert with stomach content analysis of northern pike. Minnow trapping was conducted on a bi-annual basis where 180 traps were baited with salmon roe and distributed evenly between three sections of the creek; upper, middle and lower. This effort was necessary to assess whether or not there was an increase or decrease in relative abundance of juvenile salmon and to document changes in distribution patterns over the duration of the study. For all study years, approximately 12,000 northern pike were examined for stomach contents and dietary preference. The northern pike sampled were collected from the same three study sections as juvenile salmon sampling.

Although it may still be a little premature to tout project success, there are several positive indicators that Alexander Creek salmon stocks are showing signs of recovery. Since 2011, numbers of invasive northern pike in the creek have been reduced substantially. Escapement numbers of adult spawning king salmon in the past four years have been the highest in the past decade, increasing from a low of 150 in 2008 to a high of 1,117 in 2015. Though recent escapement numbers are very encouraging, they are still far below historical levels when avenge returns hovered around 2,500 to 3,000 fish.

Visual observations during recent aerial surveys also indicated that king salmon are recolonizing historic spawning grounds in both the lower and upper reaches of the creek that have been void of spawners for nearly two decades. Although other salmon species are not specifically targeted for index surveys, visual observations from king salmon aerial surveys indicate other salmon species are increasing in abundance as well. This trend is mirrored by harvest and catch trend data generated from the department’s Statewide Harvest Survey, and echoed by reports from local area residents and sport fishers as well.

During the first two years (2011 and 2012) of the project, juvenile king salmon were only captured in minnow traps in the lower portion of Alexander Creek (River Mile 1-10), while in recent years (2013-2016) they have been captured throughout the entire length (40 miles) of the creek. The stomach content portion of the study displayed a similar scenario, where at the beginning of the study all the pike stomachs containing juvenile salmon were only in the lower portion of the creek, during the previous two years, juvenile salmon were found in pike stomachs throughout the entire drainage.

King salmon are multigenerational species in that siblings from a single spawning female may spend from one or two years in freshwater, and one to five years in the ocean environment. Given that, and the fact that these returning fish are only beginning to reestablish historic spawning grounds, it may be several years down the line before we are able to say with confidence that the project was a success.

Once this project is deemed as being fully successful, it will be necessary to continue suppression work at a reduced level on this system in perpetuity. The cost will probably run about $20,000 a year. However, that would be a small price to pay for the restoring a multimillion dollar fishery.

This project was funded through a sustainable salmon grant administered through NOAA along with a general fund match through the state legislature.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.