Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

January 2017

Documenting Steller Sea Lions

Using Time-Lapse Cameras

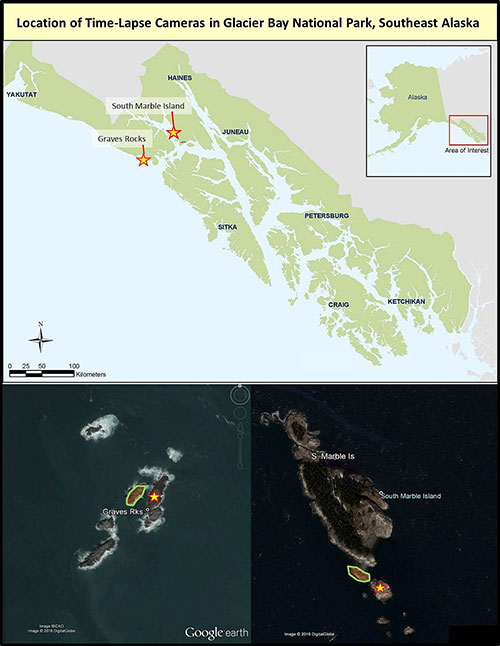

Alaska Department of Fish and Game biologists have been studying the life history of Steller sea lions throughout their range in Alaska for more than 50 years. In some areas such as the western Aleutian Islands, populations have declined more than 90 percent since the 1970s and have not shown signs of recovery. Meanwhile, overall eastern population counts have been increasing roughly three percent per year during this same timeframe. Sites in and around Glacier Bay National Park in northern Southeast Alaska were first colonized during the 1980s through 2000s and have seen even higher annual growth. This region saw an overall average increase of about eight percent per year, with yearly growth as follows: Graves Rocks about four percent, South Marble Island greater than 16 percent, and Inian Islands greater than 14 percent.

You might be wondering, “How do scientists know that all the “missing” Steller sea lions from the declining sites aren't just moving to Glacier Bay where conditions are apparently better for some reason?” Well, researchers from a number of agencies have been permanently marking a small number of Steller sea lions from various sites and documenting them during annual surveys, so they can use that information to estimate population survival rates and discern movement patterns.

The rugged coastal Alaskan sites preferred by Steller sea lions are extremely remote so the simple act of just getting there to survey what’s around is very time consuming and as they say, time is money, especially on a boat. What’s more, these surveys only really provide a short glimpse of what’s going on out there. As such, even if you encountered sufficient workable weather windows (that’s a really big if), sending people to remote sites multiple times per year is prohibitively expensive. However, in recent years digital cameras, batteries, and solar panels have seen vast improvements, coupled with decreasing costs, which means that deploying a year-round automated observation post (i.e. autonomous camera) has become a reasonable supplemental tool for collecting sea lion survival data.

During summer 2016, Fish and Game researchers installed autonomous time-lapse cameras at six sites as part of our effort to observe year-round presence of Steller sea lions in Alaska. Two of these cameras were deployed in Glacier Bay National Park at the aforementioned Graves Rocks and South Marble Island. The camera system consists of a modified, watertight, Pelican case which contains a Canon DSLR camera body, zoom lens, and supplemental battery pack. The camera is pointed out a clear acrylic viewing window installed on the side of the Pelican case. The battery is connected to a compact 20-watt solar panel and both the Pelican and solar panel are mounted to a wooden frame which is in turn secured to the ground via a combination of heavy mass (e.g. sand bags or rocks), temporary anchors (e.g. climbing nuts), and adhesives (e.g. two-part epoxy resin). The tower is then camouflaged with paint, netting, and if available any vegetation dislodged during installation (Figure 2). The camera system has an adjustable timer, 256gb memory card, and supplemental solar power so it should in theory allow for a year or more of uninterrupted observations. Mother Nature is hard on equipment, however, so we visit our cameras several times per year to ensure they’re still functioning as intended.

The South Marble Island camera was deployed during mid-August and has not been serviced since then, so we do not have any current data from this site. The camera at Graves Rocks was deployed during July and serviced during mid-August. Nautical conditions on-site during August were challenging, with large waves sweeping through from all directions (Figure 3) so surveying Steller sea lions from the boat was not a good option. The time-lapse camera was unaffected by these swells which is precisely why we deployed the camera in the first place. A quick review showed that marked Steller sea lions are clearly visible throughout the deployment period. We’ll know more about whether our camera systems are viable and produce useable data or not when we get back to service them again this winter.

Justin Jenniges is with the Steller Sea Lion Research Program at Alaska Department of Fish and Game

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.