Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

December 2017

How Old is That Crab?

In the quest for sustainable fisheries management, determining the age of commercial species is an important piece of the puzzle. Rough age estimates are often drawn from animal size; however, as with humans, size can only say so much about an individual. Consider LeBron James and Danny DeVito: LeBron is about 20 inches taller yet 40 years younger than Danny.

Alaska’s largest and most valuable crab and shrimp fisheries estimate age using size measurements, because it is the best method available. More accurate and direct age estimations could improve the assessment of stock status and productivity (e.g. estimates of survival rates, age at the onset of maturity, and the age when an animal is targeted by the fishery), which helps to determine sustainable catch levels.

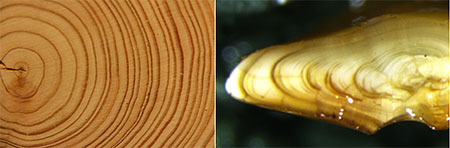

For many Alaska commercial fish species, accurate ages are determined by direct examination of hard structures like scales or ear bones (otoliths), which contain banding patterns associated with seasonal fast and slow growth, like growth rings in trees (light and dark bands in Image 1).

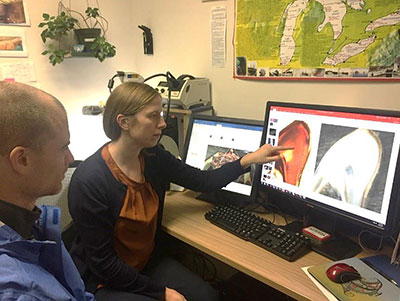

Crabs and shrimp do not have otoliths or scales, but they do have other hard structures that show potential for direct age determination. In 2015, researchers Kilada et al. identified banding patterns in stomach structures (ossicles) of snow and red king crab as well as the eyestalks of spot shrimp. That’s where our lab comes in. Operating in Juneau, within the Mark, Tag, and Age Lab (MTAL) of ADF&G’s Commercial Fisheries, the Age Determination Unit (ADU) is collaborating with University of Alaska Fairbanks and NOAA, joining a world-wide mission to explore crustacean stomachs and eyestalks as potential age structures. Following the discovery of banding patterns, we are developing the best methods to process stomachs and eyestalks to yield the clearest banding patterns for potential age determination. From there, we are taking a closer look at the ring counts to determine whether they can be used to infer age and growth. In the case of crab stomachs, the experience and results thus far have been encouraging.

Processing crab stomachs

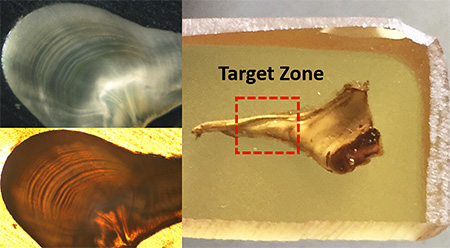

When dissected and cleaned, the stomach ossicles form a “W” shape about the size of a small pretzel (Image 3).

To begin our project, we isolated the ossicles of 20 snow and red king crab, embedded the structures in resin, thin-sectioned them from end to end with a high-speed precision saw, and looked for banding patterns within each section (Image 4). We used microscopes and imaging software to study approximately 2,000 thin sections, each about as thick as a strand of hair. Next, we located the clearest banding patterns in the structures for each species, and identified the areas from which they came as target zones (Image 4).

A closer look at indicators of age and growth

To assess banding patterns as an indication of age and growth, we focused on snow crab, which support the largest crab fishery in Alaska. Snow crab go through a terminal (final) molt which, from that point on, leaves them in the same exoskeleton (shell) for the rest of their lives. The appearance of this “retirement home” degrades in color, wear, and texture over time, allowing researchers to clearly distinguish newshell (actively growing crab, or recently molted) from oldshell crab (crab that have not molted in some time; Image 5). Mark and recapture studies have verified these differences; finding that newshell and oldshell crab can differ up to 7 years in age. Using target zone sections of stomach ossicles taken from snow crab, we began comparing band counts in the stomachs of oldshell and newshell crab.

Our ongoing research may reveal differences in the stomach structures of oldshell vs. newshell crab. If the results suggest that the banding patterns seen in their stomachs do indicate growth and, therefore, age, then we could be on our way to groundbreaking age determination methods! Studying these crustacean hard structures is a good reminder that, when it comes to the quest for sustainable fisheries management, it takes guts to do the right thing.

More information or check out the hashtag #AgeTheCrab on Instagram.

April Rebert is a biologist at the Mark, Tag, and Age Lab in Juneau and is currently an M.S. student in Fisheries at UAF. She first wrote about working with microscopes when she was in the 3rd grade.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.