Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

January 2018

‘Swarming’ Behavior in Southeast Bats

Could Reveal Key Information on Hibernation Habits

Bat researcher Karen Blejwas has documented a behavior in the small, winged mammals that will not only help her hone in on their hard-to-find winter roosts, but it will also provide valuable insights into habitat selection, hibernation timing and emergence.

It’s called swarming. It happens every fall, as the bats congregate around their roosting sites either as part of mating behavior or to teach young bats where to find a decent hibernation site. The term “swarming” may conjure up images of bees or starlings moving in unison, like a shadowy mass in the air. But unlike colonies of bats on the East Coast, bats in Southeast Alaska swarm in much smaller groups.

Still, the discovery was both a surprise and cause for excitement for Blejwas, a wildlife biologist for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

“This is cool because it opens up additional ways to find these winter roosts without having to tag and radio track bats,” she said. “There’s a lot of activity through a good chunk of the night, and it’s during the summer when bats are above ground.”

Because of this above-ground activity, and because the timing can be predicted, researchers are able to set up cameras and bat detectors in habitats they think bats are using as roosting sites. Then, they sit back and wait, letting their “tools” capture the nighttime activities.

A motion triggered camera at one of the known sites captured bats flying in circles around the entrance. Like most in the region, this roost looks like nothing more than an indiscriminate cluster of rocks on a steep, forested slope. The camera also captured bats landing and crawling in and out of the hole. In all, seven videos were logged showing this behavior not as a unique occurrence, but instead as a predictable event.

With the discovery of this swarming behavior, Blejwas said it will be much easier to locate where bats are hibernating.

In contrast, there’s a lot of time and energy that goes into tagging a single bat, which was the only other method to discover where it spent the winter. But that was just one bat, and one roost.

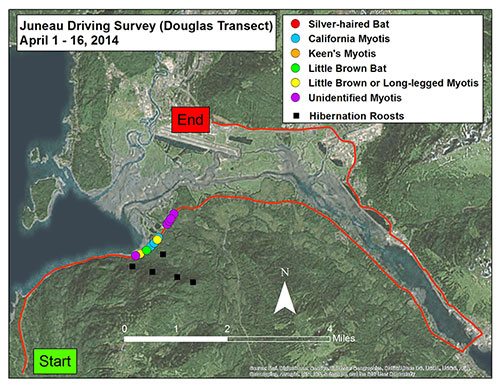

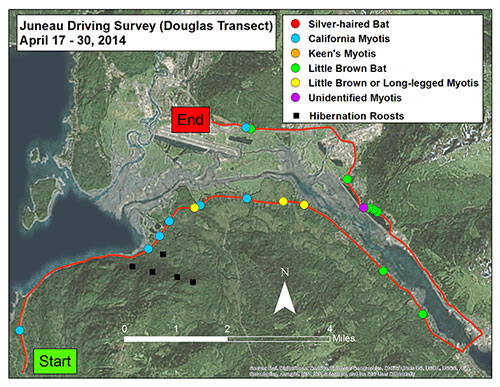

A second discovery came after Blejwas plotted bat calls from early spring driving surveys on Douglas Island in Southeast Alaska, near Juneau. Surveys were conducted with a bat detector — a device that picks up the echolocation calls bats use to navigate and find food. She noticed that in early April, all of the calls, from multiple species, were clustered near the area where little brown bats are known, based on radio telemetry, to overwinter, suggesting they were just emerging from hibernation. By the second half of April, the calls were spread out along the entire survey route as bats began moving to their summering areas.

“I got really excited about that because I think (the discovery) increases the tools we have at our disposal to figure out what these guys are doing,” she said. “We could potentially identify overwintering areas in other communities without having to do an expensive, labor-intensive capture and telemetry study.”

Further south, in Petersburg, the same behavior was recorded by a volunteer who was part of Blejwas’ citizen science program. During an evening driving survey in April, the volunteer picked up many calls coming from a steep ridgeline. While there are no known roosts on that ridge, Blejwas suspects that was evidence of emergence from hibernation and guesses there are roosts in that area.

“So I mapped out this survey,” Blejwas said. “There were these cluster points at the base of this one ridge, and I remember driving by that ridge thinking, ‘Wow, that looks exactly like the habitat that bats hibernate in in Juneau.’ And that’s where the clusters were in that first, early season survey. And I was like, ‘Holy cow, can we use driving surveys to identify the general areas where bats are overwintering?’”

That would really narrow things down. “Whether we are using radio telemetry, or some other technique to find those actual roosts, at least we have an idea of where to start looking.”

Back in Juneau, where a detector captured bat calls during swarming at that same known roost site on Douglas Island, Blejwas came across another revelation: Different species of bats may be roosting together.

“It looks like there were three different species involved, all at the same location,” she said.

Bat calls are unique to each species, and Blejwas thinks she was able to identify the little brown bat (Myotis lucifugis), Keen's long-eared bat (Myotis keenii) and the California bat (Myotis californicus).

“When we set up the detectors, we got a lot of California myotis calls there, so at least two species are present,” she said. “There are calls that look like they could be Keen’s myotis, but the calls they use at roosts … it’s a pretty high-clutter environment … so the calls tend to look more similar. So, I can’t be 100 percent sure about the presence of the Keen’s, but there are definitely California and little brown bats present at the roost sites and during the timeframe of the swarming behavior.”

Which means the different species of bats found in Southeast Alaska — at least the Myotis species — may all be roosting together.

“We’ve pretty much gotten every Myotis species around at the North Douglas site,” she said.

That’s a big deal not only because it’s somewhat of an unexpected discovery — very little is known about hibernation sites and habits of bats in Southeast — but also because it may contribute to the spread of white nose syndrome (WNS), a deadly disease caused by a fungus that often appears looking like white powder on the nose of the bat. The fungus affects hibernating bats by causing wing tissue damage and disrupting physiological processes. It hits little brown bats particularly hard, and has caused widespread mortality in eastern and Midwestern North America. Thus far, the disease has not been detected in bats in Alaska, but Blejwas is nervous because she fears it’s only a matter of time. And, even though she’s excited about the discovery of the swarming behavior and what it might mean for research, she sees a downside, as well.

“It’s not really such good news because then the white nose syndrome could transfer that much more easily between species,” she said. “If the little browns have white nose syndrome, and they go to this roost, and they spread the spores, and then California myotis bats are also using this, then they’re getting infected too. And so then it’s spreading from species to species, and not just from bat to bat.”

Any bat can carry the spores, even if they don’t end up showing symptoms.

In March 2016, a little brown bat in Washington State died from symptoms associated with WNS, the first detection of such a case on the West Coast. Spores of the fungus can be carried on virtually anything, including other animals or birds.

“The other thing that made me realize the significance of this issue is there are other animals that go in and out of these holes. Mice, squirrels and mink — depending on the size of the hole — and so there’s yet another route for potential transmission.”

The size of the roost, the distances between roosts, all affect transmission. “The conditions inside the roost — temperature and humidity, for instance — affect the growth of the fungus,” Blejwas said. “And the duration of hibernation also affects what the fungal load will be by the end of hibernation, and mortality is tied to fungal load.”

In other words, what bats are doing during hibernation really has a huge impact on how the fungus is going to interact with the bats.

Still, Blejwas said she’s “totally stoked” to learn of this new information.

In the coming year, she plans to continue to recruit citizen science volunteers to carry out driving surveys throughout Southeast Alaska and beyond. Currently, they survey in Sitka, Wrangell, Juneau, Petersburg, Haines and in Cordova.

Abby Lowell is an Education Associate with the Division of Wildlife and is based in Juneau. She wrote about white-nose syndrome in bats in 2016.

Bat monitoring and citizen science projects

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.