Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

November 2004

Ancient Indications of Angling and Ethics

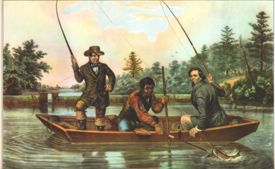

Humans have been fishing for sport as well as food for almost as long as fishing has existed. In Europe, angling for pleasure can be traced back to the first century A.D. In the Far East, sport fishing - with bamboo rods, silk lines, flies, and barbless hooks - dates back more than 3,000 years.

Parallel to this long history of sport angling are signs of the development of angling ethics. There were very early discussions about the need to limit one’s catch. Releasing fish alive may be nearly as old as the sport itself.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, state fish and wildlife agencies brought the weight of science to bear on the problem of renewing and sustaining wild fish populations. In recent decades, agencies have focused on developing a mix of management practices to ensure the health of fish populations while providing angling opportunities. Catch and release was formalized as one management tool through extensive research.

Some fisheries managers have said that “Fishing for Fun” began in the 1950s as a pseudonym for the first catch and release fisheries. Some fly fishers maintain that catch and release began with Lee Wulff’s 1939 admonition that “a sport fish is too valuable to be caught only once.” But catch and release is far more ancient in origin and practice.

From Martial’s poetry of the first century to Sir Humphrey Davy’s "Salmonia" in 1829, anglers have written about the need to release a portion of their catch. In America, the earliest discussion of the need to conserve resources and release fish comes with our first great author on fishing, Thaddeus Norris. His "The American Angler," published in 1864, was the first book published in the United States wholly written by an American angler about our fisheries. Uncle Thad, as Norris came to be known, wrote about the destruction of our fisheries and the need for resource conservation. He also wrote of releasing as many fish as he kept.

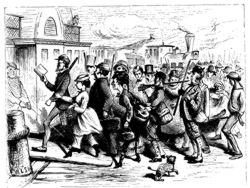

Perhaps the most influential book in the conservation movement of the early years after the Civil War was written by a Boston minister named William Henry Harrison Murray. “Adirondack Murray”, as he was known, published his "Adventures in the Wilderness" in 1869. The book went through eight printings in its first year and led to the building of over 200 “Great Camps” in the Adirondacks within five years. “Murray’s Fools” flooded the wilderness from the East Coast through the Midwest each weekend, packing specially scheduled railroad trains which ran from urban centers to wild places. This was the birth of industrial tourism that we experience in Alaska today.

Murray wrote of the need to restrict one’s harvest of fish and game to that which is needed for food, and of releasing fully half of his catch. In the final 20 years of the 19th century, editors of outdoor magazines championed releasing fish as a means of conservation. By the time of the “Golden Age” of fly fishing, during the first several decades of the 20th century, catch and release was well established as part of the ethics of responsible angling. Just a few quotes from some of the more prominent writers of the day will illustrate this.

Theodore Gordon, perhaps the most revered angling writer at the turn of the last century, remarked in 1905 on the growing practice of releasing fish. “Some say it is well to kill off the big fish. I doubt this greatly” and “I know Mr. LaBranche by reputation, and his ideals are high. He fishes the floating fly only and kills a few of the large trout. All others are returned to the water.... I fancy that a trout should be big enough to take line from the reel before it is considered large enough to kill.”

In "Streamcraft" (1919), George Parker Holden took time out from describing the habits and lures of trout and bass to declare “not the least of the beauties” of fly fishing is that the quarry is hooked “lightly through the lip.” Holden then instructed on how to release fish easily, with minimal damage. He quoted Harold Trowbridge, from Outlook magazine, Aug. 6, 1919, extensively on the use of barbless hooks. Here was perhaps the first documented example of catch and release with no intent to harvest:

“In one morning’s fishing out of fifty successive fish which I hooked I found it necessary to take only three out of the water in order to release them from the line. Two dropped off as they came over the side of the boat, and only one required an instant’s touch before the hook could be slipped from its jaw.”

Holden declared: “Do not be afraid to join the slowly growing fraternity of those anglers whose password is ‘We put’em back alive!’”

Hewitt’s "Handbook of Fly Fishing" (1933) touched briefly on releasing fish: “It is surprising what freedom and relief one feels when the basket is left home. I rarely carry one any more, as I seldom kill more than one or two fish for a day’s sport, knowing only too well how long it takes to grow these fish and how few of them are in any stream. I do not want to injure my own sport or the sport of others in future.”

In 1936, Gifford Pinchot published "Just Fishing Talk." He referred repeatedly to releasing fish.

“We love the search for fish and the finding, the tense eagerness before the strike and the tenser excitement afterward; the long hard fight, searching the heart, testing the body and soul; and the supreme moment when the glorious creature, fresh risen from the depths of the sea, floats to your hand and then, the hook removed, sinks with a gentle motion back from whence it came, to live and fight another day.”

These writings and many others led to Lee Wulff’s famous declarations in 1939 “Game fish are too valuable to be caught only once,” and “The fish you release is your gift to another angler and remember, it may have been someone’s similar gift to you.”

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.