Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

February 2020

Collared Pika

Big Questions about a Little Animal

Bears and whales are part of Alaska’s charismatic megafauna thanks to their size and appeal. Collared pikas, on the other hand, are admittedly smaller but equally charismatic due to their intrepid nature and ability to survive extreme environments. This species is thought to be an important indicator of changing alpine ecosystems.

Cousins to hares and rabbits (lagomorphs) and the size of a large hamster, pikas can be seen deftly scampering across alpine talus slopes, often carrying bits of vegetation in their mouths. The word pika (pronounced pike-uh) is derived from the Siberian name for this animal, puka. In Charles Sheldon’s iconic book “The Wilderness of Denali,” he calls pikas “conies”, which may be a derivation of the Italian “coniglio” meaning rabbit. Only two species of the little lagomorphs are found in North America - the American pika lives in mountains of southern British Columbia and the American West; the collared pika is found in Alaska and elsewhere in northwestern Canada. Collared pikas are so named because they have a white band of fur around their necks that contrasts with their dark grey coats.

In Canada, pikas were listed as a species of special concern because of their potential vulnerability to changing alpine ecosystems. In the state of Alaska, they are identified as a species of greatest conservation concern but have no formal designation under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). There have been efforts to list American pikas under the ESA in the Lower 48, and it’s important to learn more about collared pikas in Alaska so that state biologists can inform future management decisions.

Alaska state wildlife biologist Katie Christie is collaborating with researchers and biologists at the University of Alaska Anchorage, the University of Idaho, Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson (JBER), and the University of Oklahoma to better understand the distribution, demography, and foraging ecology of collared pikas in Alaska. Christie works for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s Threatened, Endangered, and Diversity Program.

“Pikas are really interesting animals to watch,” she said. “They’re in Southcentral and Interior Alaska and you can find them on high elevation talus slopes. They blend in well with the rocks. You have to be really close to one to see one, and you usually hear them before seeing them.”

They may be well camouflaged, but they aren’t secretive. They live in colonies and they are quite active in summer.

“They collect vegetation that they store in haypiles,” Christie said. “They survive winter not by hibernating or with a thick layer of fat, but by collecting plants and eating them over the winter under the snow.”

They can also be noisy. Members of the pika colony alert each other to the presence of predators, either aerial or terrestrial. They also respond to the alarm calls of marmots and ground squirrels. Ermine are major predators of pikas, but other predators include red foxes, northern harriers, and golden eagles.

“They do announce their presence,” Christie said. “They’re extremely vocal, but people confuse them with the call of a ground squirrel. The pika call is a short “eeep!!” that has been compared to the bleat of a goat, whereas the ground squirrel call is a sharp, high-pitched “tsik”. Christie said there is evidence that each pika has a unique call and can identify other pikas based on slight frequency differences between calls.

A Species of Concern

The pika’s vulnerability is thought to be their low thermal tolerance, both for hot summer days and for cold winter temperatures.

A profile of the closely related American pika on the US Fish and Wildlife Service website summarizes the issue well: “A key characteristic of the American pika is its temperature sensitivity; death can occur after brief exposures to ambient temperatures greater than 77.9 °F. Therefore, the range of the species progressively increases with elevation in the southern extents of its distribution. In Canada, populations occur from sea level to 9,842 feet, but in New Mexico, Nevada, and southern California, populations rarely exist below 8,202 feet.”

So what happens to a pika colony when summer temperatures begin topping 78 degrees?

“Pikas reduce their activity in the heat of the day, retreating to the cool spaces within the talus," said Christie. “Whether prolonged heat reduces foraging time or the ability of young pikas to disperse to new territories is unknown.”

Paradoxically, warmer winters can be bad for pikas, if the deep snow layer that covers the talus is compromised by warm temperatures. Christie said the insulative properties of snow protects pikas from the colder days of winter. A snow-covered pika den can be as much as 30 degrees warmer than the outside temperature. A rain-on-snow event, or a warm spell that melts that snow cover, followed by more cold winter weather, can result in lower survival rates.

The Big Questions

Christie said the researcher’s main objective is to gain a better understanding of this species’ ecology in Alaska, including their response to changing alpine ecosystems. Summers are becoming hotter, growing seasons are becoming longer, and there are more melting events in winter. In addition to temperature changes, the vegetation is changing, with tall shrubs gradually encroaching on alpine tundra. Some of these changes, like higher plant productivity and milder winters, could benefit pikas, whereas others, such as mid-winter rain events, may be detrimental.

“We want to understand how resilient pikas are to these changes,” she said.

Christie and colleagues are focusing on three main questions: 1) What environmental factors and weather conditions are related to over-winter survival of pikas? 2) How broad is the diet of collared pikas and do they select alpine forbs and grasses over shrubs? and 3) What habitats support the highest densities of pikas in Alaska and has their distribution changed over the past several decades?

Christie and her colleagues are focusing on three study areas in Southcentral and Interior Alaska for the mark recapture and diet studies, and sites across the pika’s range in Alaska for the distribution study. More than 100 pikas have been captured, marked with ear tags, and released. Temperature sensors and remote cameras have been placed strategically at the colonies as well.

“We have one study site at Hatcher pass in the Talkeetna Range north of Palmer, another along the Denali Highway west of Paxson,” Christie said. “The two populations offer a good contrast of more interior conditions and more coastal conditions at Hatcher.” A third, recently added study area is on the 73,035-acre Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson (JBER) in Anchorage.

“We will tag pikas at this site and initiate a study of activity patterns in relation to weather conditions. It’s great to have the interest and support from biologists like Colette Brandt at JBER.”

Talus is a key habitat feature for pikas. Talus refers to a jumbled pile of rocks accumulated at the base of a slope or cliff, also called scree. Talus offers nooks and crannies for pika dens, and storage areas for their haypiles.

“They need to be able to get under the rocks,” Christie said. Good pika habitat consists of medium-sized boulders surrounded by alpine vegetation but not too overgrown with shrubs.

How do you catch a pika?

“We lure them into live traps with native vegetation,” Christie said. “They readily go into traps to grab the plant material and bring it back to their haypiles. We mark them with colored ear tags so that each individual has a unique color combination and can be identified through binoculars.”

So far 102 pikas have been tagged in Alaska for this study. Pikas are territorial and establish their territories when they are young. Once they claim and defend a territory they tend to stay where they are, a quality known as high site fidelity. Within the colony, pikas mate with neighboring pikas.

Researchers will visit the pika colonies in July and August to document which pikas made it through the winter. Because of their high site fidelity, if they are not re-sighted on or near their territory, biologists can safely assume they are dead.

One aspect is to learn is how far the juveniles disperse in search of a territory. Pikas don’t fare well with tracking collars, they either wiggle out of them or die, Christie said. Instead, researchers will compare genetic relationships between colonies.

“The genetics of collared pikas have been well studied,” Christie said. “We are collaborating with Professor Hayley Lanier, who did her Ph.D work at UAF on pika genetics. Now she’s a professor at the University of Oklahoma, and she’s still working on pikas.

A newly established rockpile in Denali National Park offered a snapshot of dispersal. The human-created rockpile near the Toklat River offered potential pika habitat two-to-three-kilometers from the nearest established pika colony on a natural talus slope. Researchers found that pikas had discovered the rockpile and established a colony.

“So we know they are capable of dispersing at least that far,” Christie said.

Do they still occupy historic territories?

Christie is collaborating with Paul Schuette at the University of Alaska Anchorage to revisit historically occupied sites and see if pikas are still there. Lower-elevation sites are of particular interest.

“We have a database of sites going back to the ‘60s,” Christie said. “UAA has been working on that aspect of the study. The analysis is not yet complete, but it appears they occupy most, but not all of the sites they occupied a few decades ago.”

The researchers are also drawing on the work of population biologist David Hik, who conducted a decade-long research project of collared pikas in Kluane National Park in British Columbia.

“Most of our knowledge of collared pika ecology comes from that study,” Christie said.

Pika diet and cafeteria trials

“It’s fascinating to learn about how they decide what to put in their haypile,” Christie said. “It’s an insane amount of food that they stuff under rocks. Pikas need the plants dry out nicely – there has to be good air flow. Dry vegetation lasts a lot longer than moist plants.”

Pikas appear to collect whatever vegetation is available nearby and the researchers found a wide diversity of plants in sampled haypiles that varied from site to site. That said, they do have preferences. Published research suggests pikas may choose plants with secondary compounds like tannins that store better and last through the winter.

“We did some ‘cafeteria trials’ to test hypotheses regarding pika selectivity of different alpine forbs and shrubs. We were interested in whether pikas would select tannin-laden shrubs over alpine forbs and grasses” Christie said. “Plants that are nutritious when consumed immediately may not keep well over the longer-term”.

Pikas were offered a “cafeteria tray” of different foods: alpine forbs, grasses, and different species of shrubs. Six short sections of PVC tube make up a tray, and each is stuffed with a different food.

“We give them an hour, once they discover the tray,” Christie said. “We look at how quickly they take food from each of the PVC tubes. They empty their preferred tubes and just leave the ones they don’t like. They seem to prefer willow leaves and certain forbs over grasses and shrubs with thick, waxy leaves.” Christie is working with animal nutrition experts at Washington State University to determine the digestibility of each of the food types used in cafeteria trials.

The Comfort Zone

Researchers have also deployed tiny “ibutton” temperature sensors to monitor the temperatures inside the pika dens as well as outside. The sensors record the temperature six times each day and store the data. They are retrieved in the summer and the data is downloaded.

“We found the temperature inside the den can be up to 30 degrees warmer than the ambient temperature,” Christie said.

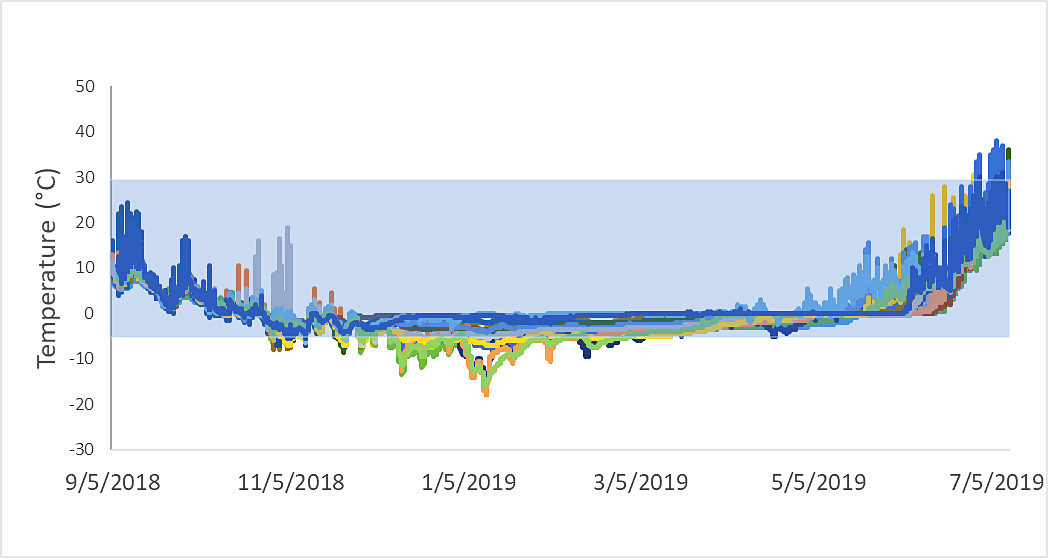

They also found that all dens are not created equal. The best dens maintain a consistent temperature range within the pika comfort zone. A graph of dens in the Hatcher Pass study area shows temperature fluctuations between early September 2018 and early June 2019. The light blue shaded area defines what is considered to be the comfort zone for American pikas. Researchers are still learning what the comfort zone is for collared pikas.

Each den is a colored line. A flat line means the den is well insulated from the winter cold, and some dens are much better insulated than others. While the temperature in all dens goes up in summer, some go up noticeably more than others.

“Some territories are better than others,” Christie said. “The yellow and blue lines show dens that get well above that comfort zone in the summer. Some are below the comfort zone in winter. The more snow there is, the higher the likelihood of temperatures staying in the comfort zone.”

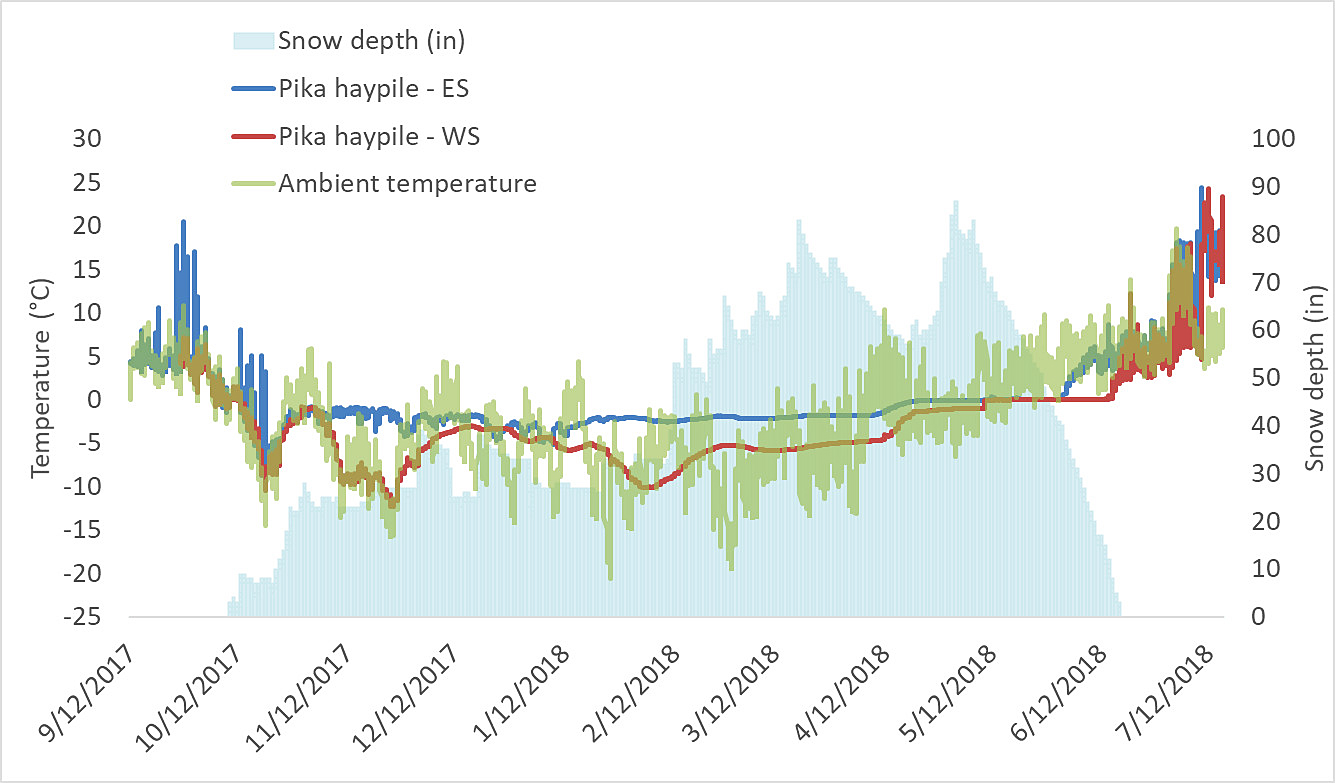

In graph 2, the light blue bars indicate snow depth, which tops 80 inches in March and May of 2018. It’s gone by mid-June and back in mid-October. The messy green line is the fluctuating ambient temperature outside, which bottomed out at 20-below in late January. The blue and red lines are two pika hay piles under the rocks.

“So before there is significant snow the temperature of the dens track the ambient temperature, but once there is snow it levels out quite a bit,” Christie said. “On coldest day of year the temperature of one of these pika dens was 32 degrees [fahrenheit] warmer than outside.”

Pikas are active in winter under the rocks and snow, avoiding ermine, rearranging their haypiles - and raiding their neighbors’ stores if they can. The cameras and sensors are quietly collecting data, and researchers will retrieve them in July.

“We’ve completed two years of field work, and the plan is to complete two more to answer our immediate questions,” Christie said. “I’d love to extend it further, but we’ll see.”

Excerpt from a BBC special on Alaska, featuring pikas and their calls

Riley Woodford is the editor of Alaska Fish and Wildlife News and produces the Sounds Wild! radio program.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.