Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

March 2020

Is it a Mountain Lion?

Using forensics for fur

Did you hear there was another mountain lion sighting in Interior Alaska? Seeing a mountain lion in Alaska is almost like saying you saw a Yeti, but not as mythical because they have been here. It’s understandable that they could come into the state following mule deer as the deer expand their known ranges. Mountain lion sightings have been reported in Alaska as far north as Fort Yukon and at least as far back as the 1940s. Most records of sightings come from Southeast Alaska but there has been very little conclusive proof from sightings of lions in the Interior.

ADF&G recently received a report of a mountain lion crossing a road and running off into the brush, so staff went to investigate. The person reporting had not been able to take any photographs, as the animal was too fast. Frustratingly, the tracking conditions were not ideal for a positive identification from the sign alone. The signs seemed to indicate cat; however, it was inconclusive from the tracks if they were made by a mountain lion or something else. By following those tracks, ADF&G staff were able to find and collect fur that was left behind in several of the footprints and attached to a barbwire fence where the animal crossed.

Fur on many animals comes in two types: guard hair and underfur. I’m sure many Alaskans have seen or pulled a clump of fur off a dog when they are blowing their coat in the springtime. What is being shed is the underfur. It is typically that soft warm insulating layer that is thin and fluffy. The guard hair is comparably much coarser and usually longer, thicker and rarely shed. Using fur alone, biologists have a few options to identify what kind of animal it came from.

One option is genetic analysis using DNA, but the hair itself is not the right kind of tissue to test. What you need is the follicle. If you pull a hair right up close to the body, you can sometimes pull out the hair follicle with the hair. This follicle contains tissue with genetic material. Scientists use DNA from the tissue to identify species, sex and sometimes with enough tissue we can identify the exact individual. This process is relatively long and expensive and requires enough follicles to test.

Patterns on the surface

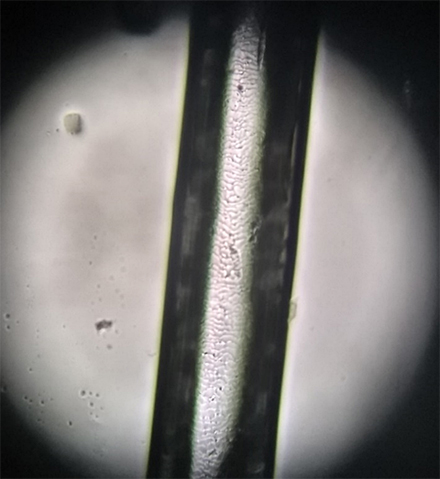

A less costly and significantly faster method to identify species using hair is by examining the pattern on the hair itself. You do not need follicles. You may have seen some shampoo commercials that show digital images of a magnified hair in which it looks cracked and peeling, then the commercial goes onto show how well that shampoo conditions and smooths out the frizzled hair. That “frizzled” look comes from the cuticular scales that are the outer lining of a hair. You have may have used a plant, bird or mushroom guide to help you identify what you are looking at, well there are also guides like these for animal fur. If we start off very simply by looking at color and length, we can begin to narrow down our options. But it requires zooming in for an even closer look to identify species. The details are in the patterns on the hair - those shampoo commercials were showing you the answer! Every species has a unique cuticular scale pattern, like a fingerprint that identifies animal species. Different patterns can be seen depending on which type of fur (underfur or guard hair) and where along the hair you look. The scale pattern changes on the guard hairs as it grows, so the pattern at the tip of the guard hair can look completely different than the portion closest to the body or midway down the hair. That means there are four different patterns (three from the guard hair and one from the underfur) that are combined to make one unique signature for each species.

To look at these scale patterns we need a microscope that can zoom at least 300x, clear fingernail polish or modeling glue and glass slides. You paint the slide with the glue, lay the hair down in the glue, wait for it to dry, and then peel the hair off. By doing that, the slide now has the impression of the scale pattern and can be seen under the microscope. Admittedly, this technique is not 100% fool-proof. Genetic testing is the far more conclusive technique because some animal cuticular scaling patterns are very similar. Even if you have all four different segments to examine, it can be a challenge for someone with little experience looking at patterns.

In the forensic feline fur case, we took fur from dog, wolf, house cat, lynx, and a mountain lion pelt and created our own references then compared them to our mystery fur. It was easy to eliminate the canines because the scale patterns were so drastically different than the felines. To distinguish between the cats, we looked at all segments and all five observers came to the same conclusion – the mysterious feline fur was lynx, so this time anyway, the lion got away.

We are still on the lookout for the elusive mountain lion, so if you can’t get a photo of the fast cat, then maybe following the tracks can lead to other types of evidence that can be used as proof. If you do spot a mountain lion (or a Yeti) please contact your local Fish and Game Office.

Kerry Nicholson is a furbearer-carnivore wildlife biologist based in Fairbanks

Cougars in Alaska from Alaska Fish and Wildlife News November 2017, with tips on how to make the most of a fleeting glimpse.

The Alaska Fur ID Project

Around 2008, staff at the Alaska State Museum launched the Alaska Fur ID project to help conservators identify the fur and hair of animals in objects in the museum’s collection. A reference set of images is available to the public free of charge, along with analysis and observations.

Alaska Native artifacts often feature mammal fur, and correct identification can inform cultural attribution, cultural meaning, trade relationships, historical period, methods of manufacture, and authenticity of artifacts. Curators wrote: “While our focus is to better understand technical aspects of Native artifacts, is also hoped that this project might prove useful to our allies in other professions such as zooarchaeology, biology and forensics.”

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.