Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

January 2021

Native vs. Invasive Pike

A Tale of Two Ranges

If you follow social media posts about northern pike in Alaska, it is common to read discussions that look something like this: “Northern pike are native here”. “No they’re not”. “Yes they are”. “Nope, not true.” – there is so much confusion about this in Alaska, and rightfully so. Turns out all these statements are correct; it just depends what part of the state the question is asked. This is because northern pike are BOTH native and non-native in Alaska, and their management in different parts of Alaska varies significantly because of this. To understand this better, let us begin with some history.

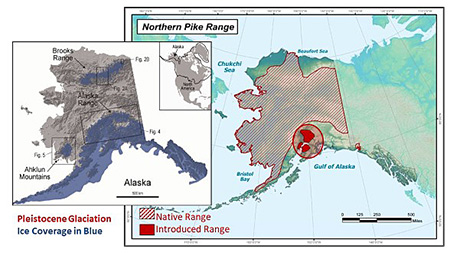

Northern pike, hereafter pike, have a native circumpolar distribution including northern Europe, Asia, and North America generally above 40° latitude. In Alaska, they naturally occur in waters north and west of the Alaska Mountain Range. However, glaciers during the last ice age locked up Southcentral Alaska south and west of these mountains, and this geologic barrier was pivotal to the development of the freshwater fish communities we know in the state today. Species like pike and Alaska blackfish were restricted to drainages in areas of Alaska that were not covered by these glaciers. Genetic evidence even seems to indicate that Alaskan pike are related to populations in Siberia. During the ice age, sea level was much lower because of all the glaciers, and this exposed the land bridge known as Beringia. Pike, like many other animals, are thought to have naturally moved between Siberia and Alaska, with fish using streams flowing through this ancient land bridge. For the past 10,000 years, pike resided in interior and western Alaska but were never in Southcentral waters. Then, in the late 1950’s this changed.

The tale of how pike came to take up residence in Southcentral somewhat depends on who you ask, but descriptions from local long-time Alaskans and homesteaders converge on the account that a pilot illegally transferred pike from the Minto Flats near Fairbanks where pike are native, and released them into Bulchitna Lake where he owned property. At the time, there was not much forethought into what would happen if pike escaped Bulchitna Lake, but years later, significant floods allowed that to happen. Pike now are widespread throughout the Susitna Basin, often through their own pioneering of new waterways. Unfortunately, this process has been sped up dramatically by many more incidences of people moving them to new waters. Today, pike have been found in close to 150 waters, and in many of those, the consequences have been catastrophic for native fisheries and the local economies that rely on them, making pike one of the worst invasive species in Southcentral Alaska.

The impacts that invasive pike have on native fish populations varies greatly by water body. Pike thrive is shallow, vegetated waters without a lot of flow. In Southcentral Alaska, habitats like this function as important rearing areas for other species like coho salmon, Chinook salmon, and rainbow trout. If pike are introduced to an area that has this kind of habitat, and the entire lake system or drainage is all pretty similar, then there is nowhere for native fish to hide from pike, and they can be preyed on quite heavily. This was the case in Alexander Creek, for example, where pike were a significant cause behind the loss of the once-popular Chinook salmon fishery there. In shallow lakes in Southcentral, a pattern repeats many times where pike get introduced and initially do quite well because they have abundant prey sources. Pike are opportunistic predators, meaning they will eat anything that they encounter. However, research studies in Southcentral have shown that if juvenile salmon are available, they are typically preyed upon first. In the worst-case scenarios, they are preyed on so heavily that every last one is eventually eaten by pike. When this happens, pike move on to other less desirable fish prey, like spiny sticklebacks and sculpins. Eventually, these populations go away too, and all that is left for pike to prey on are water bugs, the occasional duckling or mouse, and sometimes even each other. When prey quantity and quality depletes like this, the pike no longer have the energy available to support their growth, and remaining fish stay small and skinny – not usually what anglers think of when they want to go catch that trophy pike. These stunted pike continue to reproduce, but few of them get very large, and eventually all that is left is a population of very abundant and skinny “hammer-handle” pike.

Stunted pike

One of the best examples of this process was observed in Anderson Lake in Wasilla. This lake was part of a recent northern pike eradication project to protect other lakes in the Cottonwood Creek drainage and other Knik Arm drainages from pike invasion. In October 2020, ADF&G used rotenone, a fish pesticide, to remove them. ADF&G crews clean up fish carcasses after all rotenone treatments. In this lake, over 12,000 pike were removed. None were any larger than about 24 inches, and the average size was only about 6 inches. Only five longnose suckers and not a single stickleback were found. This lake was ecologically devasted by the pike, and the pike population, itself, was resultantly very stunted! The condition of these former fish populations observed during the clean-up efforts was one of the worst ADF&G has seen in twelve years of invasive pike eradication projects. The bright side is that with the pike now gone, the work of restoring Anderson Lake can begin.

So, would this happen in all waters? To some degree, pike will always prey on native fish, but if there are substantial areas of deep water or access to high flow rivers, the effects are much slower to occur, and typically much less severe because there are areas where native fish can avoid encountering pike. Big Lake is a good example of this. Pike are present, and they are most certainly preying on native fish. However, the complexity and size of that lake make it less likely that pike will destroy the fish populations and then stunt to the degree that happened in Anderson Lake. This is also one of the biggest reasons pike are not a problem where they are native. For instance, where they are native, they are a natural member of the fish community and have been co-existing with other fish for thousands of years. Western Alaska is home to the world’s largest sockeye fisheries…and has pike too. Why can balance between pike and other fish be achieved so well there, but not in Southcentral?

Fish communities

First, try and image what the complex habitats looks like in many of the huge, sockeye-producing systems in western Alaska. Drainages like the Wood-Tikchik are enormous, complex areas with very deep lakes, fast-flowing rivers, as well as shallow backwaters and wetlands. In the slow-moving and shallow waters, pike, as apex predators, are a dominant species and play an important role in shaping what the rest of the fish community looks like. In the deeper waters or fast-moving rivers, there is a different species assemblage, one where salmon are abundant and pike are rare. This is the natural balance of things as they evolved long ago. In contrast, the Minto Flats near Fairbanks, also where pike are native, has always been an area with lots and lots of pike because it is primarily all shallow and slow-moving water, and therefore, is not habitat that naturally supports salmon. Now, in Southcentral where pike are not native, similar slow, shallow habitats to those in Minto Flats, such as those prevalent throughout the western Susitna drainage, were naturally home to salmon and trout before pike moved in. That is the difference. Where pike are native, they naturally shaped the fish communities. Where they are not native in Alaska, pike are re-shaping them. In Southcentral, there is a clear before and after picture of what the fish communities looked like in many of the waters where pike have invaded. Businesses, like those that serviced the former Alexander Creek Chinook fishery, developed around these fisheries. The changes that pike have brought about in Southcentral have happened quickly, too quickly for native species to adapt, and the ecological and economic consequences have often been quite dire.

For these reasons, the way pike are managed is very different in Interior and Western Alaska than in Southcentral. In Southcentral, where pike are invasive, there is no limit to how many you can catch. You can use multiple methods like hook and line, bow and arrow, and spear. You can use up to five lines while ice fishing in some waters, and all pike you catch must be dispatched. In Interior and Western Alaska, this is not the case. Here pike are native and are an important sport and subsistence resource. When fishing for pike where they are native, always check the regulations for where you’ll be fishing to make sure you are following them and protecting these native pike resources. While it is easy to be confused about the status of pike in Alaska, it is important to recognize the difference in management and follow the regulations as they pertain to the different areas of the state. With the hardwater season upon us, enjoy ice fishing for pike (Ice Fishing for Northern Pike, Alaska Department of Fish and Game). Out west and in the north, you will have the pleasure of catching some of the greatest fighting fish there are. In Southcentral, you will have the same experience with the added bonus of helping to thin their numbers to benefit the salmon we all depend on when the ice melts.

Kristine Dunker is an Invasive Species Research Biologist, with the ADF&G Division of Sport Fish.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.