Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

February 2021

Don & Mary Williams

Stewardship on the Kobuk River

Don Williams settled in the Arctic in 1963, embracing the life and people of Northwest Alaska. He met his Inupiaq wife, Mary, there and they started a family in Ambler, befriending biologists that came north to live and work. Caribou were central to that work, and Don and Mary Williams proved to be immensely valuable. They were recently honored with Fish and Game’s Public Stewardship Award, and Don and his colleagues reflected on their decades of work together.

Ambler, home to about 300 people, is on the Kobuk River, 45 miles north of the Arctic Circle. Wildlife biologist David James moved there with his wife and toddler son in the early 1980s.

“It would have been a completely different experience if it wasn’t for Don. He made a huge difference,” James said. “Mary was very helpful to us having a young son, and our daughter was born while we lived in Ambler, too. Mary was almost like a grandmother, very kind-hearted with this very young family there. We were adapting to the community while they were adapting to us as well.”

Mary gave their daughter an Inupiaq name – her own – Qalhaqpak. “Our son then, he wanted an Inupiaq name too, so Don shared the name he’d been given, Amigrak,” James said.

Adaptation was in order as it was a challenging time. Management of the Western Arctic Caribou Herd was sensitive, in part because the population had crashed in the 1970s. Cultural differences made communication difficult, and hunting regulations weren’t aligned with subsistence lifestyles.

“I’m from the government and I’m here to help,” was not a sentiment that went over well with local people, James said. His bosses, Bob Pegau and John Coady, wanted to improve communication and relations. Regional staff was based in Nome with area offices in Kotzebue, Bethel and Barrow (now called Utqiagvik), and Pegau wanted James to live in Ambler and to visit a dozen Northwest communities at least twice a year. Kotzebue, a regional hub, is on the coast, a couple hundred river miles west of Ambler, about an hour ride in a small plane.

“Don gave me good advice about the communication style,” James said. “One question is okay. Two, maybe still okay. But three, and you’re out. They see it as being peppered with questions. He’d suggest how to bring things up, open a conversation, get people talking.”

He suggested I say, ‘I saw some caribou tracks on the way out here, but I didn’t see any caribou…’ just leave it at that. It was a more tactful way to open a conversation. I could have been up there for years and not realized it.”

Don was in a good position to help. By then he’d been in that country for 20 years. He grew up in the small town of Cambridge, Ohio, and graduated from high school in 1954. He then headed west and found work in fire control in Grand Teton National Park. In 1960 he was drafted.

“In the Army I was in transportation. I drove a truck all over Germany, over 32,000 miles in just about 20 months,” he said. He bought a camera and began a lifelong interest in photography.

In 1962, after he was discharged, he drove his Ford Econoline van up the Alaska Highway with his friend Keith Jones. Jones found work with a caribou project that brought him to the Kobuk River.

“I got a job at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, working on an ice fog project, then ended up in Barrow on a snow survey project that ended in the spring of ’63. Keith kept writing to me about the Kobuk River and Onion Portage.”

After work in Katmai and McKinley National Parks, Don landed in Ambler where he met his wife. Mary was born and raised upriver from Ambler in Shungnak. “We had three kids,” Don said. “We have 20 grandchildren and 23 great-grandchildren, and there are two more on the way.”

He and Mary built their house and shop above a slough on the edge of town. “I saw this knoll was always bare of snow early in the spring,” he said. That was the spot. They cut down trees, hauled them to the site with their dog team, and Don milled the lumber with a chainsaw.

Caribou & the Kobuk

The importance of caribou to Northwest Alaskans can’t be overstated.

“I ate a lot of meals up there with people, and caribou was typically some part of three meals a day there,” David James said. “It was vital.”

The Western Arctic Caribou Herd roams the region – an area the size of California – and at times it is one of the largest herds on Earth. Caribou populations fluctuate and the herd has reached close to half a million animals at peaks. During the fall migration the herd crosses the Kobuk River, with many swimming the river at Onion Portage, 16 miles downriver from Ambler. A significant archeological site, people have been hunting caribou and camping at Onion Portage for close to 12,000 years.

Biologist Tony Gorn, the regional supervisor for Northwest Alaska, described a fall migration at Onion Portage.

“When it was good, you’d have moments when there is no end to the caribou. There are thousands upon thousands of caribou crossing the river. I remember our staff leaning up against our boats on the south side of the river, looking out from as close as five feet away and stretching out as far as you can see, thousands of caribou crossing the river. When you have a herd as big as the Western Arctic Herd, a quarter to half a million caribou, the potential to see vast numbers of caribou is great. It’s such an incredible to place to work and live.”

In the early 1980s, biologists realized they could capture caribou as they swam across the river at and near Onion Portage in the fall, quickly fastening tracking collars and releasing the animals to continue their journey. Biologists had been using helicopters to catch caribou. Onion Portage offered a better way, but it was still a challenge. Don was instrumental in the early days developing and refining the capture technique.

“Don helped with collaring up on the Kobuk River, he supported that since the beginning,” James said. “In ‘81 I participated in what was the second river capture ever of caribou. They brought up a big, high-sided boat from Kotzebue. They’d go up to a swimming caribou, lasso it, pull it up to the boat and then lean way over and try and collar it. You’d be head down, and the caribou would be lashing out with its front hooves, beating the snot out of anyone it could reach.

“‘Use a low-sided john boat, that would work,’ Don said. It was so simple and safe, and that was the caribou capture boat from then on,” James said. “The level of support he provided just grew over the years. His help was many faceted, he was extremely helpful in so many ways.”

Don was skilled with a river boat and knew the river. He also repaired engines and could fix everything from snow machines to outboards. If someone needed a part, Don could get it. The crew often launched from Don’s yard and eventually based there, storing boats and gear at Don’s shed near his shop. He took on logistics and on-the-ground-coordination.

Caribou biologist Jim Dau said Mary also kept a close eye on the logistics and was quick to help.

“In the hustle and bustle of seven to nine biologists sorting piles of gear when coming and going, Mary was as quiet as Don was talkative, but she didn’t miss a thing in the melee of numerous conversations,” Dau said. She’d pick up that something was needed or had been overlooked and offer a solution. “Mary is the epitome of a kind, goodhearted, unflappable soul who was always willing to quietly help us solve our occasional dilemmas.”

Mary often sent fresh-baked bread and homemade cranberry sauce to the crews in camp at Onion Portage. The Williams opened their home to staff on many occasions, and Mary provided home cooked meals, usually featuring fresh caribou, while biologists waited at their house for their charter flight out to show up. That was especially appreciated when weather closed in and flights were cancelled. Don recalled one instance on Sept. 11, 2001.

“The crew had just come up from Onion Portage to fly out and all the airspace shut down,” Don said. Since they had their tent and bedding, Don invited them to stay at the house. "Jim said, ‘We hate to put you out’ but I said, ‘let’s cook up a bunch of food!’ We put on that movie, Oh Brother, Where Art Thou, they loved that. Our living room is not too big but we all fit in.”

Jim Dau worked with reindeer in Northwest Alaska in the late 1970s and ‘80s; in 1988, he moved to Kotzebue where he still lives. Now retired, he supervised the Western Arctic Caribou Herd Management program for decades. Onion Portage was a key aspect.

“I liked that project so well. It was very safe for the caribou,” Dau said. “Catching caribou with helicopters is expensive and dangerous. This was a respectful way – in the water with a boat. It was efficient. We could get all our collars out in short order, 25 to 30 collars in a few days, in some years.”

And those collars are important. “Ninety-eight percent of monitoring the Western Arctic Herd is based on information we get from having collared animals,” he said.

In 1992 biologists began inviting small groups of high school students from communities within the range of this herd to participate in the project each year. The schools often arranged for elders to accompany them and share traditional knowledge.

“They’d get millennia of information about hunting caribou, butchering, eating and cooking caribou, using caribou, how to do it right and what not to do,” Dau said. “Then they gathered information from us about mortality and range use, distribution, and numbers. It was the best merging of Western science and traditional knowledge the kids could have asked for.”

A long tradition of harvesting caribou at Onion Portage existed for local people, and continued into the 20th century with a few adaptations, including small caliber firearms and outboard motors. But those means of harvest were illegal. David James said that was something he wanted to address as a biologist working in the area.

“It was respectful, how people harvested caribou and why they did it that way. I proposed to the Board of Game and got the regulations changed. It was with the help of Don and others in this region, that we could reconcile the Native ways with the regulations. Don was instrumental in making the Fish and Game regulations compatible with the local practices.”

Don knew who to talk to when information was needed and he knew everything that was going on along the middle Kobuk River, Dau said. “He saved us a tremendous amount of money. Instead of making a lot of flights looking for caribou you could get on the phone and call Don and find out what was going on.”

Their generosity extended beyond Fish and Game, Dau said. “Don is a kind man. He helped other agencies and he helped other new people to the area. But I think with Fish and Game, Don and Mary got to know us because we stayed for years, and we got to be friends.”

Don brought another skill to the camp during the captures, one that was greatly appreciated at the end of the day.

“He played guitar, and I’m talking professional quality guitar player, not a couple chords,” James said. “He’d play with our folks when he could – he could never find enough people to play with – and he could play anything. He was really good and I always enjoyed that.”

Dau added that Don also played fiddle and harmonica. “He played harmonica in camp when he didn’t have a guitar, and he’d serenade us in the evening. We loved it. The Ookpik Waltz - he played the best version of that ever.”

Wildlife biologist Doug Larsen was based in Kotzebue between 1985 and 1990, and frequently worked in Ambler. He spent time at the cabin with Don and Mary and their family, and bought a guitar from Don, which he never did learn to play. He noted that Don’s exceptional sense of humor was also an asset.

“He had a way of laughing at his own jokes that made them funnier – and you know you’re not supposed to laugh at your own jokes,” he said. Don has a unique style with an observation and understated comment, combined with the ability to poke fun without making a person feel bad about goofing up.

“I really enjoyed the time I spent with Don,” Larsen said. “He’d always go above and beyond. He’s fun, reliable, and really handy at keeping things running. He’s all the things you’d hope to get in one package.”

Counting Caribou

Don harbored another talent that even he didn’t know about, one that eventually made him famous in the world of Alaska caribou management.

The number of caribou in the Western Arctic Herd (WAH) is estimated every one-to-three years using a technique called a photocensus. During late June or early July, mosquitoes, warble flies and bot flies force caribou to form huge aggregations on snow patches, gravel bars and windy, exposed ridges.

The radio collared animals scattered throughout the herd enable pilot biologists to locate these groups and to quickly assess whether at least 90-95% of the herd is there or, if not, to keep looking. Each morning, two to four ADF&G planes fitted with telemetry equipment radio track the collared caribou; if they are adequately aggregated a specialized plane fitted with a large format camera flies transects over each group making a series of photographs. The individual caribou on the nine by nine-inch photos are then counted, one-by-one.

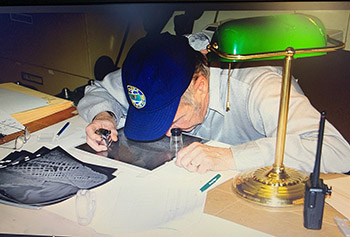

For many years biologists shared the work of counting the 800-1,200 census photos but this required time that they didn’t really have. Luckily, during the 1990s, Don was hired to help the biologists count census photos, and with each subsequent census he counted a greater percentage of them. Don eventually became the sole person counting WAH photos with biologists serving only to “audit” his work for accuracy.

“You have to be so meticulous – you’re hunched over a magnifying glass counting these little dots on a photo, tens of thousands,” James said.

“He’s counted more caribou dots than anybody alive,” Larsen said. “We used to parse it out and then he took on the whole job, all those shots of caribou – what a Godsend.”

In a 2007 article for this magazine, Nome wildlife educator Sue Steinacher described Don’s work: “Don will spend eight hours a day, from the dark of January until the spring light of March, peering through a magnifier at each of the photos and counting. Each and every caribou, hundreds of thousands of animals. One by one – except for the two-headed caribou which are actually cows with a calf tucked closely beside them. It is tedious work but Don loves it. He has done most of the counting for the last three Western Arctic Herd population censuses – enough times that he’s beginning to feel he knows each animal personally.”

“That was a good job,” Don said. “I got to pick my own hours and I even got paid for it. The biologists were always nervous, they’d check my work. Jim Dau called one day, he said, ‘I checked out your photo, you counted 321 caribou, I only got 320.’ I asked him, did you go back to look for the other one?”

Counting made people dizzy, Don said, but he looked forward to receiving a packet of new photos. “I’d have the box open in no time; I was so excited about seeing all those caribou. Some of those bunches, you’d count 14,000 caribou in one photo - you knew you’d counted some caribou then. I still have the grid sheet, the loupe, all that in my shop.”

At the same time, Don was in the Arctic Cat snowmobile business. People would come down to his shop for parts and see the pictures.

“They’d say, ‘what are you doing?’ I’d explain how it worked, show them, and they’d just shake their heads and walk away,” Don said.

In recent years high-resolution digital photography, GPS technology and computer software have improved the caribou counting process, and Don retired from counting. He turned his attention to his own photography.

Don has noticed that the Arctic is changing and the timing of the herd’s migration is shifting. “From the first day I landed in the country I kept a logbook,” Don said. “I wrote every day. I ran dogs and I wanted to know the weather.”

The caribou have been late in recent years, Don said, sometimes really late. “Last year when Fish and Game came up to do the collaring, in September like they’ve done for years, there were no caribou. They didn’t see one at Onion Portage.”

“We had one day in December we hit 36 below for a day. Then the temperature went right up and it rained. Last year it rained in December and January, little squalls. I feel so sorry for the animals, the snow crusts up and they break through.”

Don said after his counting days were over, Jim Dau invited him to help with the census for a week from the base in Eagle Creek, the first week of July. They did a lot of flying, giving Don a chance to see the caribou from the air – alive and moving.

“That was an experience I won’t forget,” he said. “Especially seeing the different local plants, birds and countryside. One evening I pulled out my harmonica and asked if they wanted to hear a tune. All agreed and I cut loose with Turkey in the Straw. Yes, I got their attention.”

Don will be 85 in July. As much as he’s appreciated by Fish and Game, he’s loved his work. “I got to know a lot of people,” Don said. “I wouldn’t have traded it for anything.”

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.